Itinerating Europe:

Early Modern Spatial Networks in Printed Itineraries, 1545-1700

Citation for Original Article:

Printed itinerary books featuring lists of cities and relative distances were a key resource for cosmopolitan travelers of the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries. This article applies Social Network Analysis (SNA) to a new bibliography of eighty-four itinerary books to illustrate a common “mental map” of routes and the impact of infrastructure, war, and cartography.

Scroll down to see the annotations.

Introduction1

Ottavio Codogno’s itinerary books were my first exposure to the itinerary book genre. I came across the title in the process of preparing my dissertation prospectus on the development of European postal systems. While my dissertation relies on Codogno’s prose, the route tables were difficult to read using the same techniques, especially once I discovered other similar titles for comparison and contrast to Codogno’s selection of routes.

In 1608, the Spanish postmaster lieutenant Ottavio Codogno took his professional expertise to a Milanese publisher, producing A New Itinerary of Posts Throughout the World (Nuovo itinerario delle poste del mondo).2 The New Itinerary detailed the pan-European system of waystations (poste) and riders in relay that had expanded from Northern Italy from the fifteenth century. The book showcased Codogno’s expert knowledge of routes from Madrid to Vienna, and Rome to Brussels, listing over two hundred examples for the use of couriers, administrators, travelers, and correspondents. The “Posts from Genoa to Mantua” or “Posts from Turin to Lyon, by the shortest road” listed locations in sequence with occasional comments on local attractions or political boundaries. In 1623, Codogno revised the itinerary under a new title, “Compendium of the Posts” (Compendio delle poste), nearly doubling the number of routes within. Yet the New Itinerary and Compendium remained physically small books intended to be carried comfortably on the road.

I was initially concerned with demonstrating how individual titles have been used in postal historiography to date. It was more valuable to point to the overall absence of consideration of such reference works as an international phenomenon, due to the natural limitations of close-reading and individual, physical consultation. The final version of the article broadens my historiographical intervention from a history of postal infrastructure towards the history of reference books and travel more broadly.

Codogno’s books are most often referenced as direct windows on to the history and administrative structure of the European posts in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Historians emphasize the novelty of postal waystations and their implementation by the territorializing early modern state. Wolfgang Behringer and Bruno Caizzi rely primarily on Codogno’s prose chapters to this end, referencing individual routes from the tables to determine where post stations were located.3 In Europa Postale, Clemente Fedele, Marco Gerosa, and Armando Serra provide new biographical context for the enigmatic postal lieutenant, including a map with routes and the number of posts recorded.4 Yet the map represents both the 1608 and 1623 itineraries, obscuring the substantial differences between the two editions and reinforcing the itinerary books as objective geographical depictions.

The miscellaneous applications of the term itinerarium became clear once I started to systematically search for other itinerary books in the road table format on union catalogues, often by using “itinerar*” in the title field of chronologically-bound queries. I was already performing similar searches for “roads'' and “posts” in various European languages. With time, I included more regional variants such as the many spellings of the German “wegweiser.” While the mention of “roads” or “posts” in the title increased the likelihood of a route table format versus a prose guidebook, there is no way to be completely sure without consulting a digitized or physical copy in many cases. I erred on the side of excluding any itinerary from the bibliography that I could not ascertain to include route tables.

The Nuovo itinerario and Compendio need to be recontextualized in burgeoning early modern itinerary book production. Before the advent of modern cartography, the itinerary book was the pinnacle of geographic knowledge. The term itinerarium referred to a listing of cities with their relative distances such as the famous Roman Antonine itinerary of Britain.5 Christian pilgrimage itineraries of the Middle Ages, such as Mathew Paris' Chronica Majora (c.1250), combined lists of cities with innovative fold-out maps. By the sixteenth century, the term encompassed a variety of travel guides, road charts, and miscellaneous collections of maps, observations, and navigational instructions.6 Itinerary books structured the European conceptualization and navigation of space through the eighteenth century, and yet have rarely been studied as a text technology and international knowledge project.7 Works that do consider itineraries comparatively are bounded by single nationalities, consulting the books as direct windows on to contemporary postal and road infrastructure, and thereby missing the international landscape of the genre.8 Agents and brokers of various professions— from state postmasters, to humanist printers and religious renegades— supplemented their varied incomes by publishing itinerary books, often in a characteristic route table format, and referring to a common canon of geographic knowledge.

I was especially steeped in the outcomes of the Mapping the Republic of Letters project at Stanford, a collaboration that also involved the Oxford Cultures of Knowledge project. See: http://republicofletters.stanford.edu/ and http://www.culturesofknowledge.org/.

Printed itineraries ferried the mail, bodies, and imaginations of a broad European readership. Much of what is known about early modern travel and exchange derives from the vast personal archives of exceptionally cosmopolitan individuals, such as Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580-1637), Samuel Hartlib (1600-1662), or Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680).9 By the middle of the sixteenth century, a wide reading public had access to key information for navigating networks of couriers, carriages, roads and post stations, from the hubs of Milan, Brussels, and Innsbruck, to Moscow, Constantinople and the New World.10 The itineraries demonstrate the key role played by postal hubs that did not leave as distinctive a mark on correspondence collections and newspaper production, such as Milan, Leipzig and Dresden.11

As chains of directional relationships, the routes were readily interpretable as a network model without prioritizing real geographic proximity as the primary organization. I could then pull out many individual metrics representing the fates of individual cities over time, but grouping these into a coherent analysis remained trickier. Reconciling a seemingly disparate set of observations remained a challenge at this stage of the article, and in network analysis as a humanistic methodology. In the final version, I focused on the overall characteristics and periodization of pre- and post-Westphalian European systems, emphasizing the advent of consensus on a canon of routes, and followed by the dissipation of the same.

The route corpus illustrates the impact of geopolitical shifts on a European “mental map” of land-based travel. The period in question — from 1545 to 1700 — encompassed the revolutions brought by the late Reformation, the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), and the beginning of the Enlightenment. Itinerary production preceded and followed the Peace of Westphalia (1648), long associated with the birth of a modern world system, allowing for the fruitful study of historic events on popular geographic knowledge.12 Interpreting cities as nodes and routes as links in an imagined network demonstrates long-term trends. Network analysis visually and quantitatively highlights anomalies, prompting further inquiry into notable presences and absences— see, for example, the surprising absences of Dutch itinerary production, and the relative conceptual distance of Spain from a network which it had played a disproportionate role in creating.13 The route corpus indicates that the mental map saw its most radical shifts several decades after Westphalia, and suggests a greater impact by formal cartography on European perceptions of geopolitical space.

Reading across itinerary books demonstrates the collaborative, transnational development of the genre. Itinerary creators inherited a canon of routes from the late middle ages and gradually shifted their selections until the overall network more closely resembled a modern topography. Mapping the total corpus of routes is simplistic: flightpath-like connections apply the modern processes by which we encounter, interpret, and navigate travel and information infrastructure. The itineraries co-existed with, but functionally differed from maps: instead of a bird’s eye view of political and geographic topology, they presented cities as semi-spatial, abstract concepts and connections. As Shawn Graham writes about Roman itineraries, “…the itineraries are not simple lists: they are records of journeys, both real and potential… they are the static presentation of dynamic relationships between the towns listed."14 Itinerary creators looked outwards on the world from a fixed viewpoint, building it into the hierarchies by which they organized the routes.15 They borrowed routes from contemporaries and predecessors, occasionally adapting them to appeal to new audiences. Characterizing the archetypal itinerary reveals an overall incorporative, collaborative process of itinerary creation.16 The readers of itineraries, who often belonged to the same class of itinerant administrators, also made the itineraries their own: they leafed across its indexes, planned their journeys, chose between alternatives, corrected information, and documented their own stops and travel experiences on the pages.17

While it is my eventual goal to work with the content information located beneath the route heading, including the number of posts on a given route, the itineraries have proved difficult for Optimal Character Recognition Technology. The irregular table structures, mixed quality photographs, ample marginalia, and occasionally damaged texts have necessitated hand entry to date. The Transkribus software developed by the READ-COOP Team has been revolutionary, and I am now at work training both layout and text recognition models tailored for the itineraries.

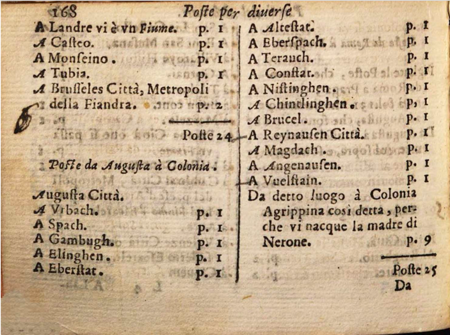

Fig. 1a:

Page from Ottavio Codogno’s Nuovo itinerario, with manuscript reader additions. Journeys are organized by headings, generally consisting of an origin and a destination (see “Poste da Augusta a Colonia”, or “Posts from Augsburg to Cologne.”) The list beneath provides all intermediary postal waystations with their respective distance in posts (“p.I”). Bayerische Staatsbibliotehek Mnchen, Res/Geo.u.86. Courtesty of the Bayerische Staatsbibliotheck Mnchen.

This figure, 1b, is emblematic of the overwhelming impulse to throw routes on a map, despite the difficulty of representing real geography with solely the header data. While these visualizations demonstrate the scope of the routes and areas of particular density, such as northern Italy, they also represent exactly the flyover mentality from which I wish to distance myself. Ultimately, I decided against including this figure in the final version, as it was too easily interpreted as an endorsement of the visualization, and was perhaps serving as a straw man in any case.

Fig. 1b:

Map of all edges indicated by the headings of Nuovo itinerario. The map overlays the network approach on geographic space, drawing a single direct connection between origin, intermediaries as listed in the route heading, and destination. The page shown in 1a appears as a single link between Augsburg and Cologne.

I compiled the database over the course of the past four years, hand-entering itineraries as I came across them during my dissertation research. Digital editions available from Google and Bavarian State Library have been particularly valuable. The database itself is a set of relational tables which I primarily access through Google Sheets. Tab and Comma Separated Data (.tsv or .csv formats) allow for smooth movement between different visualization programs.

Based on more than 70 published itineraries, the Early Modern Digital Itineraries database consists of close to 3,500 unique routes connecting more than 1,500 cities. The use of digital approaches for the history of the book has long facilitated the distant reading of text corpora to identify patterns in the early modern print industry.18 Several projects, from the Nolli Map of Rome to The Map of Early Modern London have utilized digital mapping to operationalize early modern cartographic sources.19 In some cases, such as ORBIS: The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World, scholars layer additional data to distort cartographic space, prioritizing the representation of cost and difficulty of travel over geographic distance.20 This project focuses instead on the abstracted space of the itineraries, which bore a complex relationship to both geographic and experiential realities. The organization of locations into select lists introduced hierarchy, directionality, and centrality to the communication of routes. Network models bridge the gap between textual sources and cartographic representations, acknowledging the impact of real geography, but not assuming its primacy in the inclusion, modification, and ordering of routes.

The history of the itinerary paints a rich canvas of changing European space, travel, and communication. The modern traveler can easily underestimate the value of accurate, reliable international geographic knowledge; in the sixteenth- and seventeenth centuries, few individuals could lay claim to comprehensive expertise. It was the collaborative project of a diverse cast of agents that itinerated Europe at least a century before cartographers could lay claim to the task. The accuracy and reliability of the postal itineraries could be suspect, but the accessibility was nothing less than a revolution, brought about by the building of new infrastructures, the professionalization of cosmopolitan knowledge brokers in many guises, and the wildfire growth of the printing press and ephemeral reference literature.21

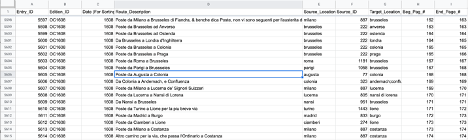

The dataset consists of a series of relational tables: an edition, a location, an overview, a route, and an edge table. The edition table preserves the bibliographic information of each edition (allowing for visualizations such as figure 2), while the location table consists of the GeoNames coordinates for each location that appears within the route headers of the database. The overview table has a single row for each entry, meaning each incidence of a route header within each edition within the database. The route table aggregates these entries by the locations and directionality (Paris to London via Calais, for example), while the edge table breaks each route down into its constituent one-to-one relations between included locations (Paris to London, Paris to Calais, Calais to London). The first edge of a route (origin to final destination) is the least geographically important given that the information is repeated in the second and third edges but reveals an important conceptual link. It is designated by a 0 in the sequence index and can be filtered from analysis. Everything stems from the “Route_Description” column of the overview table, which represents a fairly straightforward set of transcriptions of all headers under consideration. I have provided an image below that includes the interpretation of the page shown in figure 1a in the Overview and Route tables (shown in Google Sheets).

While the term “itinerary” was used by a variety of books, including many prose accounts, the chosen examples follow the established formula of a header describing a journey (“Rome to Milan”) followed by a list of intermediary cities. The resulting database distinguishes between a “route,” meaning an abstracted connection between an origin, a destination and possible intermediaries (“Rome to Paris via Milan”), and an “edge,” meaning a one-to-one relationship between locations (“Rome to Paris”, “Rome to Milan,” and “Milan to Paris”). Every effort has been made to preserve the original directionality as published, distinguishing between “Rome to Paris”, and “Paris to Rome”, for example.22

The benefits to reading across the itineraries in this matter are multifold. First, it highlights the correspondence between the itineraries, reflecting the incorporative process of their production and use. Points of convergence, and anomalous cases, demonstrate the push-pull forces of different conceptual structures of space. Second, as historians of print have demonstrated, the material organization of information offers valuable insight as to the intent of the creator, and the perceived needs of the audience.23 Interventions reveal important shifts in knowledge regimes. To put it another way, itinerary creators and their readers shared a new mental map: centers grew and shrunk, directionality flipped, and the margins became the core of the conceived European network. The itineraries were never a perfect mirror of real change; producers like Codogno used the imperfect information that they had available. Third, the consideration of itineraries as a genre recognizes the propagandizing power of postmasters and postal itineraries, as they grew to dominate itinerary production. Postal officials like Codogno had a real economic interest in emphasizing the reliability and accessibility of the subnetworks that they oversaw, particularly promoting them over historical routes with rival, entrenched local carriers.24 Yet the sum effect of many small interventions — and occasional complete reworkings — produced new models of European space, communicating them to a wide readership. By reading the itineraries as a collective corpus, we provide a new periodization for the impact of shifting travel and exchange networks across the early modern period on the overall conception of a connected Europe.25

Genome of a Genre

The 70 itineraries analyzed here are not an exhaustive survey of the genre, but do represent its overall diversity of authors, languages, times and places of publication. The peak of itinerary production within the corpus was from the 1590s-1620s, with new editions of Daniel Wintzenberger’s Reisebüchlein (1595, 1598), Giovanni dal’Herba & Cherubino Stella’s Itinerario (1598), Ottavio Codogno’s Nuovo itinerario and Compendio delle poste (1608, 1611, 1616, 1623), Theodore Turquet de Mayerne’s Sommaire description (1604, 1605) and others.26 Itineraries were published across Europe, although there is an interesting overall absence of publication from the Netherlands, especially given its role as an early headquarters for the Thurn und Taxis family of postal administrators.27 If Dutch itineraries were in circulation, we would expect to see English-language authors drawing from them, and yet these itineraries were generally translations of German and Italian examples.28 Franciscus Schottus' Itinerari Italiae (1600) had notably originated in Antwerp and continued to be produced there, yet listed routes were only ever added by Italian publishers.29 This absence could be due to continued warfare in the Netherlands, making such geographic information more protected, akin to that of the New World. It may also be indicative of a Dutch reliance on travel by sea, as the itineraries by and large focused on land routes utilized by travelers and couriers. A similar absence holds true across the Baltic, despite significant advances in Swedish postal infrastructure.30

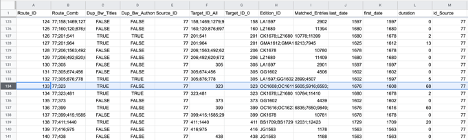

The best way of finding commonalities among the itineraries was to construct an adjacency table (shown in Google Sheets) where each common route adds 1 to the cell located at the intersection of the editions shown in the row and column names. Itineraries attributed to the same author (indicated by the initials prior to the year of publication in the Edition ID) are most likely to share a high proportion of routes. I also experimented with using dendrograms to represent this “genealogy,” but it largely communicated information that could otherwise be reasonably inferred, such as the similarity between editions of the same title and of itinerary creators of the same nationality (produced in R).

Distant reading of the routes highlights the relationships between itineraries, indicating which books had disproportionate, transnational impact over time.31 Routes from Dal’Herba’s & Stella’s Itinerario delle poste (1562), for example, appeared in many future titles, from Codogno’s Nuovo itinerario (1608), to Italian editions of Franciscus Schottus' Itinerario overo nova descrittione (1610), and even English “Ex-Jesuit” James Wadsworth’s European Mercury (1641).32 The canon consisted of several routes for crossing the Alps (from Trent to Vienna, and Genoa to Lyon); tight groups of major Italian and Dutch cities (Milan, Genoa, Rome, Venice and Naples; and Brussels, Antwerp, and Ghent); and a series of Spanish routes around the royal court at Valladolid. The exact wording of route headers such as “From Rome to Naples by the road of Valmonte and the Algiere woods” — which was published by 5 authors in 21 editions — makes coincidence unlikely*.*33

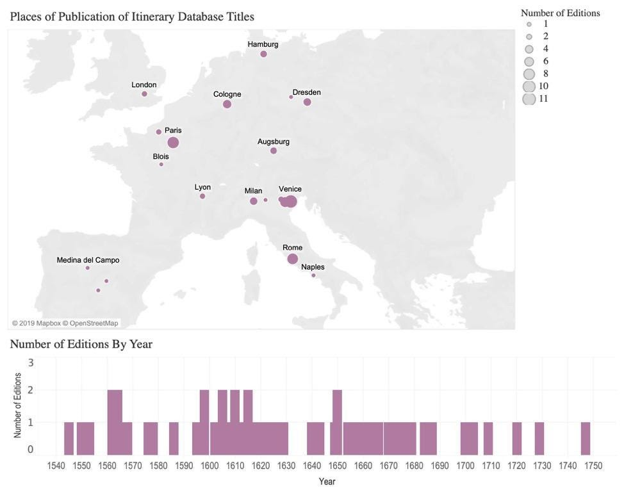

Fig. 2a:

Map and timeline indicating the publication place and date of included itineraries.

The bibliography and database contain several itineraries published after 1720, however they serve primarily as a point of contrast to the earlier itineraries. As the histogram demonstrates, the database currently is most comprehensive with regard to the seventeenth century. I used Microsoft Tableau to produce these visualizations as it allowed for the combination of maps and histograms in single dashboards. In the final version, I have graphed both the total number of editions identified for each location and year, as well as the number included within the dataset. While I generally added any itinerary I was able to consult in person or through a digitized version, I had made a special effort to represent the temporal and geographic breadth of the genre.

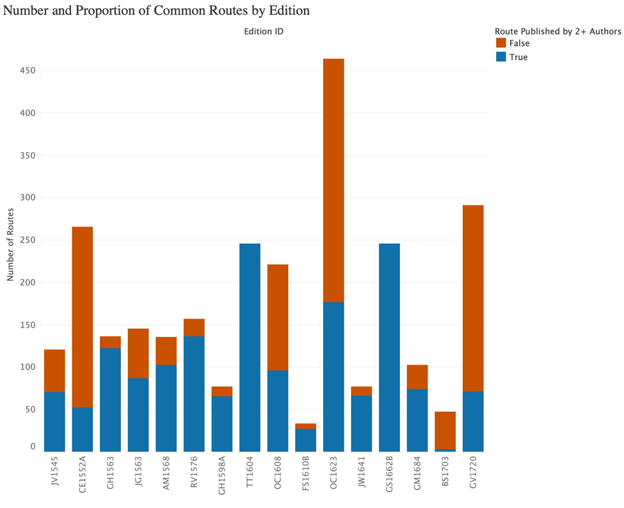

I selected the editions that are referred to most frequently in the article, and that demonstrate a variety of republication proportions. The relatively individual route compositions of Charles Estienne (CE) and Giovanni Maria Vidari (GV) contrast to that of Theodore Turquet de Mayerne (TT), which was reproduced in its entirety by Gilbert-Saulnier du Verdier (GS). The style of notation by initials and publication date (occasionally followed by a letter to indicate one of multiple editions in the same year, as in GH1598A) is a unique identifier (the Edition ID) that allows for easily linking information across the relational tables of the database.

Fig. 2b:

Bar chart of selection of itineraries demonstrating the number of routes as well as the proportion of routes appearing in an itinerary published by another author. Edition ID’s represent the initials and publication date of a given itinerary.

The digital approach also brings to light the geographic scope of collaboration. For example, while British renegade Richard Verstegan indicated that his work was an agglomeration of a “German” itinerary, as well as other French and Italian examples, we can say with some surety that he was working from Georg Mayr’s Wegbüchlein (1576).34 We can also see important shifts within the work of single authors: Codogno’s Nuovo itinerario (1604) focused on the dal’Herba & Stella-derived canon, but by the 1616 edition, it was significantly expanded, adding at least 76 routes.35 Many of these new routes may have derived from Augsburg schoolmaster Jörg Gail’s Raißbuechlin (1563) and French doctor’s Theodore Mayerne’s Sommaire description (1604).36 As Mayerne had himself explicitly incorporated the entirety of French publisher Charles Estienne’s Guide (1563) — and may also have borrowed from the German Mayr’s Wegbüchlein— Codogno’s Nuovo itinerario was the culmination of several decades of such international collaboration.37 Overall, the number of commonalities among these five titles is more than twice of that gained from random sampling across the corpus: this suggests that their relationship was more than the documentation of common infrastructure.38 Close reading of the common routes provides further verification, with many of them consisting of the same intermediary stops.

While the route tables themselves can offer further evidence as to audiences, these questions are best supported by a combination of close and distant reading as well as integrating the paratextual material of the itineraries (such as the author’s letter to the reader).

We see from this common genome the manner in which itinerary creators read across existing works. In some cases, the process of incorporation was explicit: see, for example, the Suite of Roads in France, Spain and Italy and other Places (La suite de la guide des chemins tant de France, d'Espagne, Italie et autre pays) produced by publisher Benot Rigaud and his sons. The Suite combined Charles Estienne’s Guide, dal’Herba’s Itinerary, and an additional set of routes for pilgrims involving their native Lyon.39 In cases such as the English itineraries, or the Italian republications of Schottus' Itinerari, the translator also indicated their reliance on other books. These compilations suggest that early modern readers had access to a variety of such itineraries, even when located far from the original places of publication. Itinerary publishers had a commercial reason to gather such examples, but in many cases, they may already have done so as a result of personal interest or professional imperative. Many occupations —including but not limited to bookselling—required international correspondence and knowledge of distribution networks.

I often use the term itinerary creator in the article to indicate both the author and publisher. Both frequently intervened with regard to the route tables, but it is not always clear who had the primary agency.

Yet the evidence that authors frequently republished routes with few changes also provides an important caveat for the use of the itinerary network as an exact proxy for real-world conditions. The routes in dal’Herba & Stella, Schottus and Mayerne were republished with little variation until well into the eighteenth century, despite ample infrastructure shifts in the intervening period. A 1610 edition of Schottus' Itinerario denoted a route from Milan to Brescia as “where there were posts and now are not.” In 1675, a new edition still lamented the now long-absent posts.40 In other cases, single titles were hugely reworked between editions. stretching the term “edition.” Each version of Estienne’s Guide saw modifications, most significantly between the 1552 and 1553 editions, when at least 40 routes were modified from the original.41 Several titles saw complete reworkings of their routes under new publishers in the eighteenth century, including Franciscus' Schottus' Itinerario: Roman publisher Michel’Angelo and Pier Vincenzo Rossi modified or added 13 routes of the total 28 (46.4%), all of which were located in Italy.42 Occasionally, creators seemed to target entirely new audiences: Wintzenberger’s Ein Naw Reyse Büchlein (1577) (“New Travel Booklet”) and Der Kramer und Kauffleute Reysebüchlein (1578) ( “The Agent and Merchant’s Travel Booklet”) had no routes in common, although they covered similar geography.43 Itinerary creators (whether the original authors, or future publishers) did change routes as a response to shifting infrastructure and audience demand. Modified editions and titles also showed two general trends: first, they stretched the boundaries of the original work in most directions. Second, they consolidated existing routes in many cases, dropping shorter regional connections in favor of longer-distance connections to capitals. These trends may indicate both that itinerary creators received feedback on the inaccuracy of regional routes in the intervening periods. They may also have sought to market future editions to a more international clientele based on the success of the first editions.44

I constructed the database with an aim to preserve as much of the original meaning as possible, while avoiding reading in additional layers. This approach is well modeled by the Grand Tour Explorer project, which seeks to provide a “digital transformation” of a source rather than an entirely renewed digital encyclopedia. (see https://grandtour.stanford.edu/). Modality is very rarely (almost never) indicated in the route headings, and so deduplication and disambiguation would have required substantial intervention. My choice of filters reflect my research questions, however the data remains accessible for framing new questions in future iterations.

The form of the early modern itinerary lends itself well to the construction of a network model of cities linked by these “imagined journeys.” Yet the construction of any network does require informed, interpretative choices, particularly the selection of nodes as actors, and a designated relationship between those actors as edges.45 At its simplest, the itinerary network model presumes a single, directed relationship for each route — the journey from an origin point to a destination. The introduction of intermediary locations in the route heading adds another layer of complexity: while the road may remain the same, the implied relationships of a route changes depending upon its description as “Milan to Rome,” “Rome to Milan,” or “Rome to London (via Milan).” I chose to distinguish between each of these variations, however I did group all routes by their headers alone. Journeys from Genoa to Barcelona by sea and by land, for example, will appear as a single route: while problematic for a geographically accurate map, both journeys establish a conceptual link between the abstracted cities for the network model.

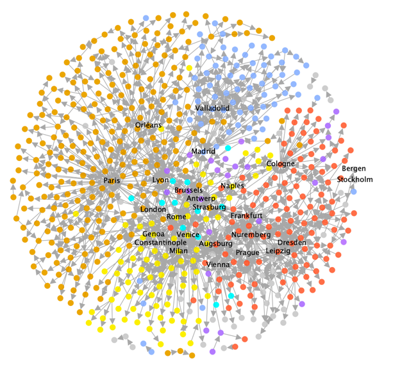

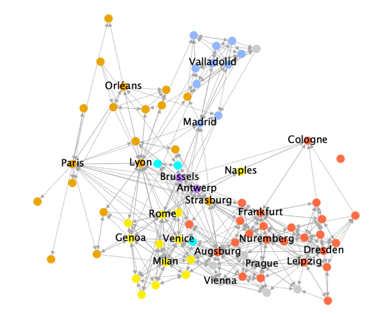

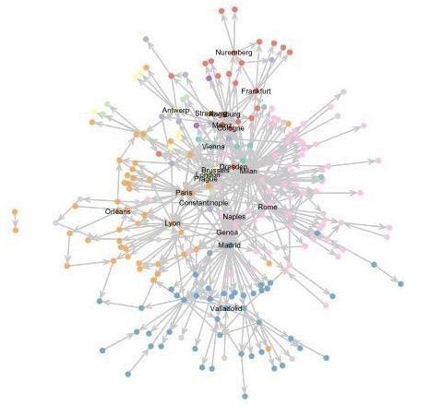

A comparison of a map and force-directed network visualization (Figures 3a-3c) demonstrates the strong influence of other factors than simply geographic proximity in the structuring of the itinerary route corpus. In Figure 3a, a force-directed graph layout positions nodes by simulating the pulling forces of shared connections.46 The nodes have been colored by modern nationality groupings to further indicate the divergence from a modern mental map.47 In many cases, we do see communities formed primarily by geographic proximity. Yet the most abstracted model indicates a core of transnational routes between cities, despite their relative geographic distance. For example, Spain appears as a visible community in the non-spatial network, with international travel largely branching to and from Madrid. France’s initial hierarchical structure breaks down, with Paris continuing to structure the French network, but many French locations demonstrated to be equally, or more often, connected to external locales. Nodes such as London, Antwerp, and Augsburg are pulled from the margins to the conceptual core of the corpus network, despite the geographic distance of the cities from their network neighbors.48 Instead of spatial positioning, this model privileges the number of connections drawn by the itinerary creators as a proxy for closeness.

This network visualization was produced within Gephi using the Geolayout plugin (https://gephi.wordpress.com/tag/geolayout/). While possible to do in R, I found that Gephi offered the most flexibility for producing a visually similar spatial and non-spatial network models. It is not an exact geographic layout- slight changes have been made to ease scale and legibility, such as reducing the distance between Constantinople and Italy. I chose a subset of cities to label across the visualizations based on which show interesting change over time and help convey a sense of geography, even in the non-spatial network layouts.

Fig. 3a:

A spatial network of all edges as published by multiple authors, colored by modern nationality.

The use of a subsection here and a highlighting box in figure 6c were both suggested in the course of workshopping this paper as means of better conveying arguments using the network model. Network visualizations have gained a certain notoriety as “hairballs” meaning that they convey interconnectedness and little else to a reader. A visual language of color, labeling, layout and juxtaposition helps to overcome these shortcomings. See Scott Weingart, “Demystifing Networks,” scottbott.net, Dec 14 2011, at http://www.scottbot.net/HIAL/index.html@p=6279.html.

A Fruchterman-Rheingold force-directed network layout. A spatial relationship still emerges by virtue of the strong connections within geographic regions, but major cities form the central axis, despite their relative distances. Cities featured in a high proportion of domestic to international routes are pushed to the margins of the network despite their high degree; see, for example, Cologne, Naples, and Valladolid. On the right (3c), filtering the same layout by degree >= 10 reveals the international core of the network.

Fig. 3b & 3c:

It is possible to calculate these network metrics using either Gephi or relevant packages in the R or Python programming languages. The easiest web platform tool is John Ladd, “Network Navigator,” Aug 30 2019, at https://network-navigator.library.cmu.edu/.

Both visualizations highlight hubs, from a complex of Northern Italian cities, to the political capitals of Madrid, Paris and Vienna. Other hubs are perhaps more surprising to early modernists, as they have not been as widely studied as centers of transit and communication: Leipzig, Dresden and Milan. An itinerary was published in each city, while two authors were postal officials in Milan and Dresden. Even when those titles are removed from consideration, the cities retain a higher-than-average degree, meaning numbers of connections to other nodes.49 Our understanding of communication and exchange networks necessarily derives from the surviving archives. Historians of information have long emphasized the hub roles of capital cities like London, Madrid, and Paris. It is worth noting that Milan, Leipzig and Dresden all saw ample destruction of archives in succeeding centuries, from the Thirty Years' War to the twentieth century. The itineraries corpus suggests that on the basis of shared network characteristics, the role of these cities is worth greater attention by historians of pan-European communication and exchange.50

In a history of Europe’s diplomatic couriers, E. John B. Allen begins a chapter on routes by stating: “if one thing is plain it is that the merchant and pilgrim routes were not those used by the post riders.51” In fact, by refocusing from the abstract infrastructure on the mental maps employed, published and sold by postal professionals among other agents, we see pilgrimage and mercantile routes continued to exercise conceptual power, even in “postal” itineraries. The analysis of the relative importance of cities within the itinerary corpus requires a more nuanced approach than the sheer number of their connections. As humanists, we might describe a city as important not just by the quantity, but also the quality of its external ties. Social network analysis (SNA) offers several metrics that are of use here, which additionally remain constant, regardless of the network’s visual layout.52 The “centrality” of a point can be a useful proxy for quantifying importance to the overall route corpus. Centrality metrics indicate that merchant and pilgrim routes played a key structuring role in the worldview referenced, reprinted and employed by postal agents among other itinerary producers.

This method has been primarily employed by Ruth and Sebastian Ahnert in their consideration of Tudor networks. I picked up this approach from the Early Modern Digital Agendas and Networking Archives seminars, which is now well represented in a new volume (available as an open access Ebook): Ruth Ahnert, Sebastian Ahnert, Catherine Nicole Coleman, Scott B. Weingart, The Network Turn: Changing Perspectives in the Humanities (Cambridge: 2020).

Betweenness centrality provides a metric of the likelihood of the shortest paths within the network to pass through the given point.53 A point with high betweenness centrality is often regarded as a key broker within a social network, by virtue of its control over network flow. A point with many connections, or high degree, will tend to have a higher betweenness centrality, so a scaled measure (dividing the centrality by degree) can provide a more comparable metric. Without scaling, the highest-ranking cities remain similar to the above noted hubs. With scaling, a new set of French cities rank highly, particularly in Normandy (Caen), and the Pays de Loire and Centre-Val de Loire regions (Amboise, Blois, Orléans), and Nouvelle-Aquitaine (Bayonne, Bordeaux, Poitiers). These are joined by the Spanish region of Castille and León (Valladolid).

At the outset of this project, I knew very little about the Camino de Santiago, outside of a brief encounter during my time at the Archivo General de Simancas. The digital findings drove me back to the original sources, at which point I made the connection. It is always a challenge to demonstrate how a digital methodology reveals news insight by comparison to traditional methods. In this and many other cases, the digital surfaces new research directions, which can be further reinforced through traditional evidence, such as prose excerpts.

The relatively high centrality of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine, Loire, and Castille and León regions can all be associated with the more than 2,000-kilometer-long pilgrimage trail known as the Path of St. James, or the Camino de Santiago. The distant reading of the routes in the itinerary demonstrates the long-lasting impact of the path on the overall conceptualization of European trade and travel. Even the relatively geographically and politically marginal city of Santiago de Compostela — home to the sacred shrine of St. James — ranks disproportionately highly in scaled betweenness centrality. The route was an early translation from manuscript to print, and frequently advertised within the itineraries as a separate addition. The first route of Codogno’s New Itinerary was not one from his native Milan, but rather “the posts from the Most Holy House of Loreto ending in Saint Giacomo of Galicia.” The reprinting of this popular religious journey well represents the reliance of the Nuovo itinerario on generations of prior itineration.54 Most scholarship on the path focuses on the Middle Ages, yet the itineraries demonstrate that it continued to have deep cultural — and religious— resonance through the seventeenth century.55 Ample military conflict likely further restricted options for travel between France and Spain across the Pyrenees, making the route uniquely important to holding together the overall mental map of Europe. On the other hand, we see the importance of Normandy, with a high betweenness centrality deriving from the channeling of traffic to and from its northern ports: early signs of a trend that would strengthen with the meteoric rise of London in the eighteenth century.

Representing this data as a map instead of a network or table guides analysis back in the direction of real journeys, as well as reintroducing key terrain elements, such as the Alpine and Pyrenees mountain ranges. The network metrics have been calculated in Gephi, exported, and then reimported into Tableau for these visualizations. The plain grey backgrounds function as a minimalist background without adding anachronistic political divisions. While I experimented with maps that included more terrain elements, I found these to be more useful for the research rather than the presentation stage of visualization.

Map of route locations colored by betweenness centrality rank (darkest gradient being the highest rank) and map of points along the historic Path of St. James. High betweenness centrality indicates the likelihood of connections in the network to pass through a given node, demonstrating that the path of St. James continued to play a uniquely important role connecting Spain and France.

Fig. 4a & 4b:

Fig. 4a & 4b: Map of route locations colored by betweenness centrality rank (darkest gradient being the highest rank) and map of points along the historic Path of St. James. High betweenness centrality indicates the likelihood of connections in the network to pass through a given node, demonstrating that the path of St. James continued to play a uniquely important role connecting Spain and France.

The eigenvector centrality algorithm is similar to those used by major search engines to order results: it weighs the quality of the connections not just of the point in question, but also of those to which it is connected. In a social network, an individual with high eigenvector centrality might be someone who was friends with “all the right people."56 In this case, eigenvector centrality brings forth many regions familiar to scholars of the Thirty Years' War as notable battlegrounds, from the Rhineland-Palatinate, to Bavaria, Lombardy, and the Piedmont. Yet the highest ranking cities by eigenvector centrality tended to be cities in smaller regions, many of which were located near to the Alpine passes: the St. Gallen pass (Schaffhausen); Splügen and St. Bernard passes (Bergamo, Lindau, Chur); Brenner pass (Villach, Innsbruck, Graz); and the St. Gotthard and Simplon Passes (Simplon, Bern, Lucerne). Locations associated with the Simplon Pass rank especially highly, despite the relative difficulty of the passes, only made tenable with the construction of the Teufelsbrücke (“Devil’s Bridge”) over the Schöllenen Gorge in the thirteenth century.57

Map of route locations colored by eigenvector centrality rank (darkest being the highest rank) and map of the historic Roman Way (Romweg) as depicted by Erhard Etzlaub’s Romweg map (Nürnberg: c. 1500). High eigenvector centrality indicates the connectivity of nodes to which a node is itself connected. Transalpine commerce continued to connect the most influential cities by way of a limited number of Alpine passes.

Fig. 5a & 5b:

Fig. 5a & 5b: Map of route locations colored by eigenvector centrality rank (darkest being the highest rank) and map of the historic Roman Way (Romweg) as depicted by Erhard Etzlaub’s Romweg map (Nürnberg: c. 1500). High eigenvector centrality indicates the connectivity of nodes to which a node is itself connected. Transalpine commerce continued to connect the most influential cities by way of a limited number of Alpine passes.

The prominence of these cities demonstrates how the itineraries were often structured as journeys to and from such natural gathering points: a traveler might arrive from a number of directions, and depart in a similarly diverse manner. We see how the itineraries functioned similar to an index, presupposing both the most common content and structure of the queries that readers would bring to them. These limited passes — which are joined, to a lesser extent, by several notable sea ports — were key transit points for travel and exchange. By comparison to network studies of Europe based on newspaper datelines or correspondence data, a model based on the itineraries highlights these key brokers, well-familiar to contemporary travelers and administrators.58 At the same time, the itineraries enacted the centrality of these locations by organizing the routes around them, raising their profile to sit alongside more populous or wealthy cities. Cosmopolitan users of the itineraries were likely familiar with them, in the same way a modern traveler might know a region primarily by its international airport.

These metrics and the overall network visualization indicate how structurally dependent the conceived European system was on these fundamentally limited channels. The importance given in the itineraries to the mountain passes of Europe reflect the real limitations on the flow of information and people in a pre-modern age. Scholarship on the Thirty Years' War often focuses on the courtly theaters and battlegrounds of central Europe, yet the itineraries remind us of the fragility of a network dependent on fundamentally limited paths for communication and mobility.59 We can see why warfare in the Palatinate and the Grisons might have reverberations in the communication and exchange networks across Europe, but also how such conflict took place in a key area of the European mental map. Scholars have addressed how the prolific broadsheets of the Thirty Years War would have made readers at a distance more familiar with these regions, yet the itineraries suggest that these regions may not have seemed all that far to begin with. Readers may have brought some familiarity, and perhaps even some understanding of the implications that disruption would bring for pan-European connectivity.60

As in most studies of ephemeral press, the possible scope of readership remains complex. Codogno’s itinerary was circulated among contemporary administrators of several nationalities, and the postmaster lieutenant advertised it to a wider public, expressing the view that the Tassis family of postmasters had established the posts “not just for the convenience of their princes and lords, but also for the common good (commune utilità) of all businessmen (negotianti).” New editions were published in Venice in 1611 and 1676. The Tassis imperial postmasters in Venice shared a copy with their cousin, the postmaster general in Brussels.61 A later Venetian administrator lauded Codogno as “the best author, who had distilled the finest matters of governing the posts and couriers."62

The appeal of the itineraries to a burgeoning class of semi-official state agents and long-distance businessmen (negotianti) is apparent and supported by the prefatory materials and limited marginalia. Giovanni Torriano’s Della Lingua Toscana-Romana, or, An Introduction to the Italian Tongue (1657) included a number of dialogues, including postal negotiations.63 One such dialogue contains the exchange between a British traveler and Italian companion, “I have the giurnal in my pocket/ What Scottus?/No, the post-book."64 The rare snippet indicates how both figures could be familiar enough with Schottus and postal itineraries to refer to them in a casual short-hand, while also carrying one or the other on the road. Governing administrators also referred to the books in making administrative decisions, as they did in debating the relative merits of the “old” and “new” roads from Italy into France.65 A 1673 copy of French itinerary Le Voyage de France (1648) contains the signature of “D. Juan Gaspar Zorrilla”, linking the book to the Duke of Osuna, counselor of the Spanish King.66 The printed itineraries were published by, and accessible to, a diverse audience. Historians of news and communications have also shown how the mixture of oral, visual, scribal, and print modes could diffuse through a much wider swath of society.67

The initial results from data analysis took me back to secondary sources as well as primary sources, as I ascertained whether researchers of other media (using digital and traditional methods) had seen similar results.

In most cases, the paratextual materials of the itineraries called attention to their inclusion of pilgrimage routes; the structuring effect of the mountain passes is inferable, if not as explicitly noted. Yet in a third key respect, analysis of the itinerary routes indicates a mental map that was somewhat at odds with itself: the placement of Spain. While geographically far from the heart of Europe, given the strong connections between Spain, Italy, and Austria — as well as the continued prominence of the Path of St. James — we might reasonably expect to see a greater network proximity between Spanish cities and other European centers. Ottavio Codogno dedicated his first itinerary to the Spanish governor of Milan, and later editions to the Spanish postmaster general. Even the prominence given to the route of St. James, often referred to as a patron saint of Spain, may have indicated an effort to appeal to such Spanish patrons. Yet Spain remains one of the most well-defined communities within the network model, with few links to nodes of other national grouping. The contributors to News Networks in Early Modern Europe note a similar distance in networks of early modern newsletter production, indicating Spanish dependence on intermediaries, and inferring that a poorly integrated postal network might be the cause.68

Distant reading route tables and close reading paratextual material does not always provide a harmonious picture. This case was one of important contradictions, revealing a fundamental tension in the genre.

The itineraries offer a very different spatial organization than a traditional hub-periphery model of empire. The majority of authors and publishers were not themselves Spanish, Burgundian, or Austrian, but frequently resided in territories occupied or ruled by the Habsburgs, such as parts of the Holy Roman Empire, or Spanish Lombardy.69 As the overall directionality of the routes indicate, Spain was a distant destination rather than origin point. By comparison to destinations in the Netherlands or across the Alps, where geographic distance was collapsed into direct abstracted links, the journey to and from Spain was exaggerated, with journeys further characterized as over difficult terrain, subject to political disruption, and lacking in necessary postal waystations. Spain’s communication and military channels were frequently threatened by French incursion into the Pyrenees passes and the Spanish Road.70 In fact, Codogno’s Nuovo itinerario (1608) featured two routes between Milan and Madrid, one qualified as “the shortest, when the French permit passage."71 Travelers and couriers were routinely captured and subject to harassment by local and military officials. Both Figures 3 & 4 indicate an overall absence of locations in the southwest of France, the site of much disruption in the course of the French Wars of Religion. The distance of Spain, by contrast to paratextual material that seeks the affiliation of client to patron, indicates the influence of experiential knowledge on the communicated mental map.

In other cases, itineraries were produced in territories that were openly hostile to Habsburg rule: see, for example, James Wadsworth’s foreword to his English translation, which disavowed the many “Catholic superstitions” inherited from the original Italian text (likely referring to location annotations referring to reliquaries), or the Venetian editions of Codogno’s itinerary, which removed its original dedications.72 While the convergences of the itinerary corpus can tell us a great deal about shared imaginings, we should not lose sight of the different, and sometimes conflicting ideologies and identities guiding their production. Despite documenting infrastructure increasingly put into place by the Habsburg imperial project, such as the Thurn und Taxis posts, the itineraries were most frequently produced far from the royal courts. Ephemeral print both echoed and amplified an imagined community.73 The distancing of Spain speaks to contemporary difficulties of reconciling Spain’s newly dominant role in Europe and the world. The ancient routes of pilgrimage and trade connecting cities across the Alps and Pyrenees continued to be held in common, but the combined forces of experiential knowledge and geopolitical reckoning pushed Spain to the margins of the international network. Whether the distancing of Spain better reflected the real experience of travel, or the conflicted views of itinerary creators, the network model allows us to visualize and explore the push-pull forces at work in shaping conceived space.

Original iterations of this article juxtaposed spatial/non-spatial, static/dynamic models much more strongly, making the case for a non-spatial dynamic model. Overall, this version now relies on a spectrum of interpretations and visualizations, matching the approach to the question being asked in each section. No one visualization method is wrong, but can be unsuitable to answer a given research question.

Network Dynamism

Based on the static networks alone, one might wrongly conclude that little changed in patterns of European travel and exchange from the fifteenth century through the eighteenth. In fact, a dynamic network model reveals key structural shifts: while inherited mercantile and pilgrimage routes continued to be republished into the seventeenth century, they played a diminishing structural role in the overall conceptual network.

The depiction of dynamic networks remains a challenging problem based on the tendency of animated visualization to overwhelm, rather than inform. Working with the mentioned R packages allowed for moving between static and dynamic visualizations. See Alex Brey, "Temporal Network Analysis with R," The Programming Historian 7 (2018), at https://programminghistorian.org/en/lessons/temporal-network-analysis-with-r

In order to consider the corpus as an evolving body, I introduced a temporal element in the form of the published “lives” of routes and edges. Like the new postal infrastructure of the sixteenth century, the published routes inherited and overlaid centuries of commerce, communication, and pilgrimage — this is made particularly clear by the most frequent relationships that appear across the routes in the corpus: Rome to Naples, Milan to Brescia, Rome to Venice, and Lyon to Grenoble. Routes, once published, entered a wider public consciousness as an abstraction of physical space, but also a concretion of the idea of a connected Europe. The routes hierarchized cities based on perceived reader demand: just as a search engine might suggest a frequently traveled route, the itinerary creators predicted where and in what direction their readers would travel.74 We can therefore think of these routes as having lifetimes as ideas, as defined by their first and last published appearances. The parallel is not exact, particularly as the ideas of the routes certainly predate their appearance in print, and certainly continue to be referenced years after their final publication, if in other forms.75 Yet the period of active publication represents that of the greatest impact of a given route, as each instance of reuse suggests a continued evaluation of applicability by itinerary creators. The “death” of a route is accomplished by either its absence from future editions, or reincarnation in the form of different cities and directionalities. The rise and fall of certain cities, the growth and decay of routes, and the varying pace of change between infrastructural development and its documentation in popular reference works has much to tell us about European space. By keeping these methods at the forefront of our approach, it is possible to consider the routes together as a dynamic corpus from which itinerary creators sourced their material, and added or removed elements as they deemed best. The resulting model offers a dynamic view of the overall project of itinerating Europe that can be read atop its physical geography, but is ultimately an abstracted network of only semi-spatial relationships between cities.76

The analysis of the route data in combination with the close reading of the itineraries indicates four clear periods: the first published itinerary books appeared from 1545-1565, with examples like Villuga’s Repertorio (1545) and Gail’s Raißbuechlin (1563). By 1565, we see the advent of the postal itinerary genre, particular in Northern Italy. Works like Dal’Herba and Stella’s Itinerario (1563) combined newly-developed postal routes with historical routes of pilgrimage and commerce. It is likely that the plague of 1575/1576 and renewed military conflict across Europe contributed to the relative lull in publication between 1575-1600. 1600-1630 saw unprecedented itinerary production with encyclopedic scope, from Mayerne’s Sommaire (1604) to Codogno’s Nuovo itinerario (1608) and Compendio delle poste (1623). 1635-1680 saw few new titles, but many republications of existing works. Once again, we might point to plague (1630) and military conflict as a likely cause for a lull. In fact, it was not until the final period of 1680-1740 that new titles appeared, including Giuseppe Miselli’s Burattino veridico (1682) and Giovan Vidari’s Viaggio in pratica (1718).77

While these assumptions and filters will rightfully invite questions and even pushback, they make explicit several assumptions that are often implicit, such as the continued relevance of republished material. Similarly, while the analysis does exclude information, it includes a great deal more information than would be possible in a traditional selection of case-studies

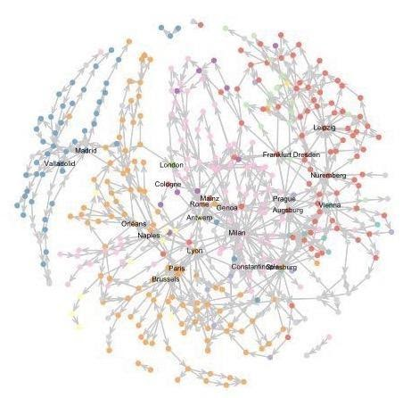

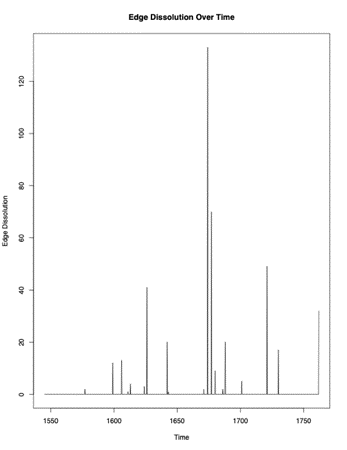

The networkDynamic package in R aids in the creation of a dynamic network model, and the extraction of many static networks to represent time-slices. We can thereby refine this periodization, offering further evidence for when important shifts in the genre took place. New routes often repeated the same edges, meaning individual connections between cities: the most significant changes to routes broke or connected cities in different ways, creating or removing the edges of the network. By graphing incidents of edge formation and edge dissolution, we can identify overall trends, and offer new insight for the overall periodization of transit and exchange in this period, as conceived by the itinerary creators and propagated by their books. Two significant filters are in effect: first, only routes that appear across multiple authors are under consideration, second, locations have been filtered for a minimum degree of two. These filters have been applied to balance the impact of highly anomalous itineraries and routes, in keeping with the goal of illustrating the logic common to many authors, as well as for simple legibility of visualization.

The choice of timeslices is always a matter of balancing subjective and objective divisions. In this case, the unit of each timeslice (35 years) is uniform, but the dates are chosen with an eye to contemporary political events and traditional historiographical periodization.

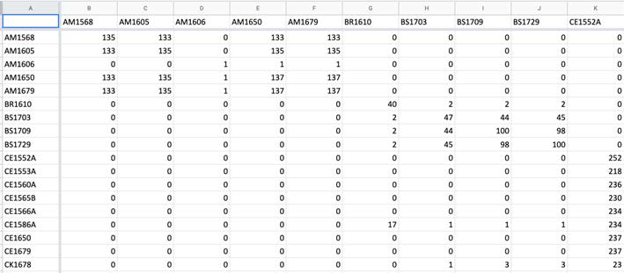

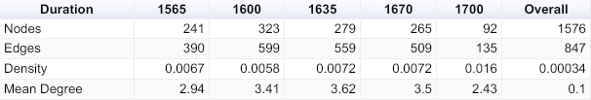

Table 1:

A table representing the network properties at any given timeslice. The density refers to the ratio of connections present in a network to total possible connections (i.e. all nodes being connected to all others). Note that the overall trend is towards increasing density, although the mean degree peaks in the middle of the seventeenth century. The standardization of routes reduced the size and diversity of the route corpus.

Table 1: A table representing the network properties at any given timeslice. The density refers to the ratio of connections present in a network to total possible connections (i.e. all nodes being connected to all others). Note that the overall trend is towards increasing density, although the mean degree peaks in the middle of the seventeenth century. The standardization of routes reduced the size and diversity of the route corpus.

A network extract of active routes in 1565 demonstrates the limited international connections in a largely segmented corpus. Many communities have a tree-like appearance, illustrating how the itineraries were structured as regional journeys branching from major urban centers. The core of the network featured capital cities (Madrid, Rome, and Paris), however it primarily consisted of commercial and demographic powerhouses: Lyon played an equal role to Paris, Milan an equal role to Rome.78 Augsburg, Frankfurt and Nuremberg appear particularly prominently as the channels to and from the Holy Roman Empire, due to both their commercial significance and strategic position for transalpine commerce. Polish commercial centers like Wrocław and Gdansk were notably incorporated, while the Hanseatic cities that had dominated trade in previous centuries were largely absent. Venice remained within a largely Italian subnetwork, reflecting the intra-European and land-based focus of the early itinerary corpus, which only sporadically included the city as a way-point on journeys further East. The core of the 1565 network reflected the geographic heart of Europe, but also indicated that commercial connections were of primary interest to the early itinerary creators.

The network model allows us to visually and quantitatively appreciate the scale of shifts between the earliest itineraries (beginning from 1545) and the 1560s advent of the postal itinerary subgenre. The earliest published itineraries had structured their routes with a domestic, short-distance traveler in mind. The postal itineraries looked to a more international, longer-distance traveler. The median distance of routes published prior to 1560 was only 113 km, while the median of those added from 1560-1580 was 243 km. Only 7.7% of routes published prior to 1560 were international, while more than a third of those added from 1560-1580 were.79 During the period of most encyclopedic publication (1600-1625), the median distances and rate of international to domestic routes remained constant, but the variety of routes increased instead, particularly along the southwest-northeast axis all the way from Rome to London. Itinerary creators drew heavily upon the existing literature, but also pushed it further in a few noteworthy routes, following new postal infrastructure across the Alps and the English Channel, but also Russia, southern Italy, and the New World.

“Small multiples” allows for the representation of dynamism in a static form. I have kept the labeled cities and national group colorings consistent across visualizations in the article to further invite comparison and contrast across the article. While I am only able to address a subset of cities in the article text, an interested reader will be able to follow cities such as Constantinople or Naples across the visualizations.

Network extracts dating from 1585, 1600 & 1635. The earliest route networks relied on a core of Madrid, Genoa, Milan and Lyon, reflecting the early influence of the postal itinerary subgenre. By 1600, the route corpus had become much more interwoven, with the structuring effect of the Spanish road becoming apparent. New locations such as London and Constantinople reflect the expanding scope of the itinerary genre. By 1635, the connections representing the path of St. James appear as a separate chain beneath the dense core, as indicated within the blue box.

Figures 6a, b, c:

By 1600, the core of the network had become more diverse, with international connections weaving together European space. Even prior to Codogno’s Nuovo itinerario (1608) — which was avowedly propagandistic in favor of his Habsburg, and Thurn und Taxis patrons — we see the structuring effect of the new infrastructure on the network.80 Like the path of Saint James and the “Roman Way,” the Spanish road is best understood as a number of routes utilized by Spanish administrators to move letters, goods and men, and between Italy and the Netherlands.81 The Dutch Revolts (1568-1648) and Anglo-Spanish War (1585-1604) drove the improvement of postal routes. The number of connections to Antwerp and Brussels increased until 1600, while Strasburg rises to new prominence.82 Sites along the strictly defined Spanish Road by Geoffrey Parker - Genoa, Mont Cenis, Turin, Lorraine and Luxembourg- show only modest gains if they appeared at all, reinforcing that contemporaries chose between varied routes and often relied instead on the St. Gotthard, Simplon and St. Bernard passes.83 Finally, nested within the largely French subnetwork, we find an early outlier: London, connected only by way of Paris, Calais, and Antwerp. London under Elizabeth I (r. 1558-1603) had entered on to the world stage as a center of diplomatic intrigue and international commerce. The itineraries from this point forward now grouped it among the major destinations of European traffic, suggesting a new expansion of Europe’s conceptual boundaries.

By 1635, the network had only slightly altered, with Genoa increasingly playing a core role, and the network of eastern destinations reachable from Prague developing in diversity and complexity.84 Once again, we see a correspondence with both the Habsburg imperial project and the work of their Thurn und Taxis postmasters, as the infrastructure established during Emperor Rudolf’s residence in Prague (1583-1612) affected the itinerary route corpus. Prague, of course, took on entirely new significance following the Defenestration of Prague in 1618, and the beginning of the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648). Like London, the city gravitated towards the center of the conceived European space. On the whole, the network’s central axis is a tightly connected, multi-directional series of links between the Habsburg capitals of Madrid, Brussels, Prague and Vienna, all linked through Italy. By comparison, the network model conveys the fragility of connections to and from France and Spain. The Path of St. James persists, but in the form of an almost entirely separate axis (shown within the box below the major component in Fig. 6c). A once key structure for the itineraries gradually became vestigial, with new infrastructures providing the primary organizing logics. The separation of the axis indicates how the connections — once building blocks for other routes as well as the path — remain as a genre trope rather than fundamental component.

This was a result that I had not predicted upon beginning the project. While the digital method can occasionally be hidden by the following return to close reading, it is worth stating here that the initial surprise of the results took me down a new road of inquiry, particularly reconsidering the role of cartography.

The most dramatic shift in the network dates to the period of greatest edge dissolution, around 1680. The crowded transnational core, and particularly the transalpine connections, were replaced with a more linear network in appearance. The overall density of the network increased, but the number of nodes was less than a third of the number at its peak.85 This was not due to a lack of itinerary publication: new itineraries published after 1680 contributed nearly 1,000 entries to the database. New titles included Miselli’s Burattino veridico (1684), new editions of Schottus' Itinerarii (1700), and Peter Lehmann’s Die vornehmsten Europäischen Reisen (1703). It is worth reiterating that the model as established is limited to routes published by multiple authors, meaning that this shift can be interpreted in two ways: first, that authors published fewer routes in common with the past, and second, that authors published fewer routes in common with their contemporaries. In either case, we see a clear departure from prior practice.

The radical shift in structure illustrates the end or re-organization of several long-running titles. It demonstrates how new titles standardized the route corpus, likely due in part to the influence of new infrastructure and ideology.

Figures 6d and 6e:

The dynamic network demonstrates that after 1680, itinerary creators structured European space in fundamentally different ways than they had prior. The cities included, the types of connections between them, and the overall structure of the conceived European systems of communication, travel, and exchange were altered. Several titles that had been republished for more than a hundred years fell out of a favor, replaced by relative newcomers. The network model illustrates how these new itineraries, while standing on the shoulders of their predecessors, reorganized much of the geographic narrative. It would be difficult, if not impossible, to appreciate the scope of this shift without the network model- particularly given that several editions were published under the same titles as they had been for the past century, obscuring substantial alterations in content.

The two postal itineraries produced by Northern Italian postal officials encapsulate the difference in organization logic developed over time. Whereas Codogno’s Compendio delle poste (1623) drew direct connections between major cities, Vidari’s Viaggio in prattica (1720) followed along long, regularized roads. Note the new prominence of cities such as Frankfurt, London, and Leipzig.

Fig. 7a & 7b:

A comparison of the structure of Codogno’s Nuovo itinerario (1608) with Giovanni Maria Vidari’s Viaggio in prattica (1720) demonstrates the structural shift on a smaller scale. Like Codogno, Vidari was a northern Italian post official, writing from Venice in place of Codogno’s Milan. Codogno’s itinerary is representative of much of earlier seventeenth-century itinerary production: journeys from and between a central transnational core wielding notable political and commercial power, with more regional routes radiating outwards from respective hubs. The Habsburg capitals of Naples, Brussels, Madrid and Prague predominate. The Vidari network is instead structured by chains of connected locations, derived from long headings such as “the road and posts from Paris to Madrid, passing through Orleans, Blois, Poitiers, Bordeaux, Bayonne, San Gio. De Luz, San Sebastian and Burgos.” Codogno’s Compendio (1623), which was encyclopedic in scope compared to its contemporaries, mapped 436 routes connecting 242 locations. Headings in Vidari’s Viaggio composed fewer routes (286), but drew links between more than twice as many locations (428).

How might we explain these differences? First, we might note the visible dissassembly of the Habsburg axis. A number of state posts had risen to challenge the Thurn und Taxis posts within the Holy Roman Empire, most notably the Swedish post during the war based in Frankfurt (1632-1635), followed by the Kurbrandenburgisch-Preussische Post based in Berlin (1649), and Kursächsische Post based in Dresden and Leipzig (1651).86 As indicated earlier, both Dresden and Leipzig demonstrated a higher-than-average degree across time, predating the foundation of these independent systems— see, for example, the itineraries produced by Dresden postal official Daniel Witzenburger in the 1570’s, and the later German edition of Giuseppe Miselli’s Il Buratinno veridico by Leipzig publisher Christian Coelii.87 Reading across the itineraries demonstrates how early that prominence began, providing important context to the eventual independence of these infrastructures.

Second, we can note the decreasing diversity of routes. By the late seventeenth century, the itinerary network showed the impact of the rising modern state. In 1718, Charles VI had ordered the reincorporation of all Thurn und Taxis posts into a single body, and Empress Maria Theresa (r.1745-1765) followed suit, ordering visitations throughout the Austrian territories and forcibly seizing control in the Tyrol.88 Seizures preceded the institution of new controls on freedom of movement, from customs to passports. States also channeled resources towards road building, making a few options much more appealing than others. The effect on the itinerary network was to thin and lengthen it, pruning its many options into a select few. Visually the networks closer resembles the grand roads of the eighteenth century, rather than their original dense network of routes.89

The itinerary network did not reflect the pace of real-world changes, but rather their slow percolation into reference materials. The Peace of the Pyrenees in 1659 settled long-standing French and Spanish conflict upon that frontier. 1660 notably saw an international postal conference held in Paris, with new accords between the French and Imperial postmasters (with routing reworked in 1668 as a part of the Aachen peace treaty). Continental transit to and from England was surely affected by the Anglo-Dutch and Franco-Dutch Wars of the 1670s, with all trade between France and England briefly banned in 1678. These changes took time to affect the historically conceived European network, but by the 1680s, their effects are apparent. A new edition of Codogno’s Itinerario (1676) continued to feature the old route between Paris and London by way of Dieppe, and several routes in the Netherlands unwise for a traveler or courier in that decade.90 By 1682, Giuseppe Miselli’s Il Burratino veridico would focus instead on routes that passed through the increasingly popular Calais.91 Leipzig was conspicuously absent from Codogno’s itineraries, while it featured quite prominently in Vidari’s Viaggio (1720) and others.92

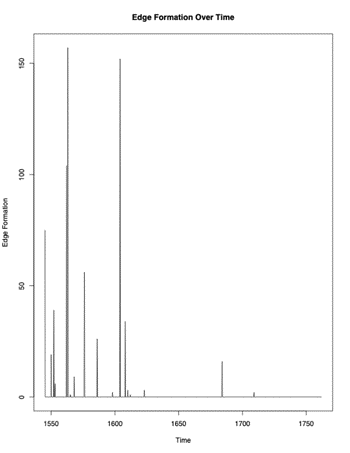

These graphs are produced in R, see Brey, "Temporal Network Analysis with R.” While visual network layouts always have a random element, the graphs represent the underlying quantitative changes.

Graphs of edge formation and dissolution in the networks over time. While the 1560s and 1600s saw the addition of many new relations between cities, the 1680s saw the disappearance of many of the same from the route corpus.

Fig. 8a & 8b:

In this way, structural shifts both reflected and impacted the fate of individual cities. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, few international connections are present in the itineraries, outside of a series of routes linking Milan, Prague and Frankfurt. While located along the same general courses as Augsburg, Nuremberg and Regensburg, Frankfurt had notably unseated these cities in the hierarchy created by the corpus of routes.93 This is somewhat anomalous given the historical and bibliographical context: unlike Dresden, Leipzig, or Milan, Frankfurt was not a site of itinerary production within the database. In fact, Frankfurt’s rise to prominence in the itineraries had more to do with the longstanding pattern of increasing traffic along the south-east, north-west axis. Frankfurt also served a dual purpose in connecting Bavarian and Northern Italian cities with France, as routes had been deliberately shifted to avoid dependence on Cologne from the middle of the seventeenth century.94 By 1702, the Thurn und Taxis family branch of Brussels had also notably resettled in Frankfurt.

With the rise of cities like Frankfurt, came the displacement of other historical hubs: Milan, Augsburg, and Lyon had long been at the core of the European network. These cities had been some of the most populous and wealthy in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Agreements between the regional messengers of the cities and the Tassis posts had been some of the earliest ordinary routes in Europe. Yet we see that by the eighteenth century, their role had been significantly diminished. As with all long durée shifts, it is difficult to pinpoint any single factor, however one likely answer seems the rise of travel by sea. Milan, Augsburg, and Lyon remained landlocked, while cities like Marseille, Livorno, and Genoa provided crucial links to a developing global network of trade and travel.

Conclusion

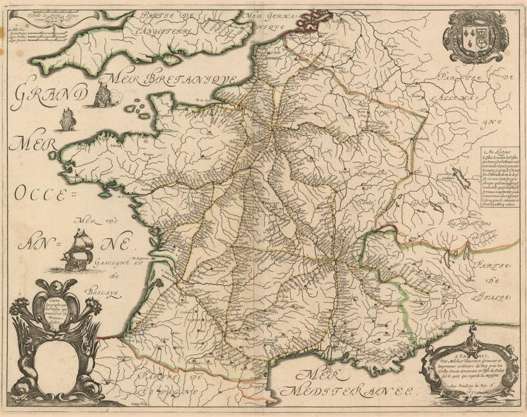

In 1632, Nicolas Sanson published Carte Geographique des Postes qui traversent la France with royal privilege, the first known printed postal map. The map marked the cartographic entree of the young royal geographer, made a councilor of the state the same year that the post was officially opened to private users in France (1627). In many extant versions, national borders have been highlighted as well as the postal lines, represented by a line dotted with the individual postal stops and occasionally numbers denoting the number of posts. The French posts are shown as far as London in England (via Calais), Brussels to the northeast, and St. Jean de Luz to the southwest, the Camino de Santiago stopped abruptly at the French-Spanish border. The permanence of that line is betrayed in a copy held by Princeton library, where the former border at Salses has been roughly expunged and redrawn to the south of Perpignan.95

Fig. 9

Nicolas Sanson’s Carte Geographique. The map charted postal routes, but only those within France’s borders.

Fig. 9: Nicolas Sanson’s Carte Geographique. The map charted postal routes, but only those within France’s borders.

The advent of the postal map did not mark the end of the itinerary, but did begin a new chapter in geographic knowledge. In fact, the map affected a very different image and purpose than the itineraries: compare the densely connected international network circa 1600 (Figure 6b) to the map above. While both included many of the same routes, Sanson’s routes were sharply circumvented by national borders. The field of vision was limited to France, with Paris, Limoges, and Lyon forming a central triad. Mayerne’s Sommaire (1604), republished in 1629, had accorded a much more prominent role to Metz and Nancy, which channeled traffic from Paris further east. In Sanson’s depiction, Metz was the end of the line, while Nancy was reduced to one of several stops en route to Basel. Germany, Switzerland, Italy, and Spain consist of sparse cities distributed along riverways, but largely empty space, contrasted to France’s finely ordered infrastructure.

Sanson’s map was an early example, with the postal map coming into vogue from the 1690s into the eighteenth century. Many scholars have made the case for the mutual development of cartography and the modern nation-state’s territorializing and surveilling agenda.96 Cartographers of the seventeenth century and beyond often received patronage from state or religious institutions, and produced maps for the explicit purpose of furthering and showcasing infrastructure. While originally produced for the elite, many maps made their way to a wider audience, even incorporated into itineraries. Later editions of Peter Ambrosius Lehmann’s Die vornehmsten Europeaischen Reisen (1703) included a detailed fold-out map (titled Besondere Post und Reise Carte der Wege durch Teutschland) with heraldry indicating regional sovereignties and Frankfurt dominating the network. Like their audiences, itinerary creators increasingly applied maps to organizing spatial relations. Cologne printer Lambercum Andree even used the maps as a method of abbreviating his routes in his Wegweiser (1597), referring readers to the illustrations instead of listing all cities. An early example, Wegweiser has an anomalously large number of routes (464 routes) and low proportion of routes in common with other authors (38%, or 177 routes). Paratextual additions also evolved, from early inserts of pilgrimage paths and merchant’s tools for the conversion of currencies and mileage, to the state-instituted timetables and tariffs of travel.