For Wagrassero's Wife's Son:

Colonialism and the Structure of Indigenous Women's Social Connections, 1690-1730

Citation for Original Article:

This project grew out of frustration with account books as a source for Indigenous women’s history. The original concept for my book project was a methodologically very traditional one, focused on Haudenosaunee women’s economic lives in the 17th and 18th centuries. For this kind of work, there are a handful of 17th and 18th century account books that document specific purchases by named individual women. These account books are mainly repetitious lists of who bought what when, without much other detail, which makes them difficult sources for traditional close reading. The specific sources I examine in this piece are known in my subfield of Haudenosaunee history, but not widely analyzed because they include relatively few individuals who appear in other documents.

This piece, and my own methodological shift towards digital humanities methods like social network analysis, grew out of a realization that I was dealing with a type of evidence that was unmanageable with traditional close reading techniques. I had lists upon lists of who bought what, and sometimes who it was bought for, and no way to make sense of those relationships. My own path into digital humanities methods started with a search for flow-chart making software to make sense of the hand-drawn map of relationships I was seeing in my sources, before I ever realized that network analysis existed as a method.

Abstract

Publication conventions for ethnonyms in early American scholarship have been changing in the past several years; at the time I wrote this piece in 2015-2016, there was some movement towards endonyms such as Haudenosaunee, but some venues preferred more widely used exonyms such as Iroquois, which was ultimately used for the final version of this piece. More presses and journals have moved towards endonyms in recent years.

This article uses digital humanities social network analysis to examine Native women’s roles in overlapping familial and economic social ties revealed in two early Dutch account books. Taken individually these records are difficult to fit into broader analyses; many of the individual Native people who appear in early account books are recorded only once or at most a handful of times and rarely appear in other documentary sources. The contrasting structures of two contemporary Haudenosaunee and Munsee social networks reconstructed from these account books illustrates the extent of colonial views into Indigenous social life and colonial perceptions of Indigenous women within their communities. Where Haudenosaunee women were visible in these networks as bridges between Indigenous kin groups, Munsee women were perceived as pushed to the margins of their own kinship networks, illustrating the process of erasure in the settler colonial archive.

keywords: Iroquois; social networks; colonialism; New York; gender; Munsee; methodology

My interest in the visibility and colonial archival documentation of Indigenous women reflects consideration of multi-scalar analysis done by archaeologists Barbara Voss, Steve Silliman, Kurt Jordan, and others. Multi-scalar analysis in archaeology considers fine-grained analysis of single sites, the context of a single site within its larger settlement, individual movement between sites, and broad social, political, and historical context. This methodological approach informed my own conception of what might be made visible in close and distant reading of archival material through methods like social network analysis.

In late September 1703, an unnamed Mohawk woman bought a shirt for a child. She gave Evert Wendell, a trader in Albany, New York, “one not very good beaver and another beaver” for the shirt. Although she traded with Wendell for eight years, he never identified her by name, and yet in the process of recording her purchases, Wendell recorded her central importance to a web of kin and economic relations. “Arija’s mother,” as Wendell identified her, was recorded first in relation to her closest male kin as Wendell made sense of indigenous kinship ties through the lens of European expectations, and the shirt was purchased for “Wagrassero’s wife’s son,” identified again through a male figure Wendell may have thought of as a head of household. Arija’s mother sent another unnamed Mahican woman with payment of a debt and purchased rum through an unrelated Mohawk man—the mundane connections of everyday life which bound communities together and were rarely recorded, or recorded women in ways that erased their social individuality, like Arija’s mother. By examining connections like these in two contemporary networks, colonial perceptions of indigenous women’s roles in their own communities can be made visible. In the Haudenosaunee network Arija’s mother was part of, Wendell perceived women like her to be important bridges between intra-Haudenosaunee sub-communities, while a contemporary trader perceived Munsee women as having been pushed to the margins of their own communities.1

The process of working with the data for this project pushed me towards questions of absence, erasure, and agnotology. These questions are always present in Indigenous history, but digital humanities work sharpens their importance because computational methods do not allow for ambiguity or absence.

Historiographically, the issue of cause and effect for Indigenous land loss and self-determination is one of the major questions for the subfield of Indigenous history in early America. Approaching the account books data through the lens of the historiography helped me understand the significance of the contrast between the two networks.

This article examines Native women’s roles in the overlapping kin and economic ties in Haudenosaunee and Munsee communities by analyzing two credit account books which documented Indigenous kinship and social ties in the course of recording purchases, debts and payments. These briefly mentioned social connections are difficult to make meaning of using traditional historical methods, but taken together they build Indigenous social networks as perceived by European settlers who recorded them. Digital humanities methods, such as the social network analysis approach here to reconstruct colonial understandings of Indigenous social ties, have been pioneered to work with much larger sources of data than are typically available for Indigenous history. This article argues, first, that digital humanities methods, of which social network analysis is but one example, have both limitations and potentials for scholars of Indigenous and other groups who did not leave the copious written records upon which digital humanities methods rely. In the case presented here, social network analysis reveals a shift from colonial understandings of Native women as central to Indigenous networks for groups such as the Haudenosaunee which were entangled in colonial systems but not wholly subject to them, to colonial perception of Native women as marginalized in their own communities for groups such as the Munsee which were more heavily impacted by settler colonial pressures of land loss, population pressure, and loss of political self-determination.

My focus in this piece was on the contrast between the closely contemporary Indigenous networks and how they were understood by settlers, but working through the significance of network structure in this piece made apparent for me that differences between how settler and Indigenous networks are recorded needs study as well.

Social details were often the only way I was able to distinguish between multiple relatively anonymous people. Many women had accounts of their own but were only noted as “Indian woman,” “female savage,” or similar. I erred on the side of caution and gave each individual a unique identifying number if it was not clear from social details such as “Arija’s mother” or “Wagrassero’s wife” that an “Indian woman” on one page was the same “Indian woman” on another page. The close reading of these social details in order to encode identification for social network analysis made me realize that the traders had to understand the social context the Indigenous women lived in out of necessity, even if the traders' own social context made them believe the women’s names were unnecessary to record.

The two contemporary account books examined here reflect these shifting colonial understandings of Indigenous social networks in the ways they recorded Native customer’s identities. In Albany, New York, Dutch heritage trader Evert Wendell kept an account book of trade with Six Nations Haudenosaunee and Mahican customers between 1696 and 1726, recording debits of payments made and credits of goods purchased carried over for months or even years under the name of an individual. The Ulster account book likewise recorded social and kinship ties for the purpose of tracking debits and credits. Kept in Dutch by an unknown trader first in Kingston, New York, and later in Ulster, New York, between 1712 and 1732, the Ulster account book recorded accounts with both Munsee and European customers. The Ulster account book did not record ties between Munsee and European customers, so only the Munsee network is analyzed here. Both account books are among the earliest direct records of Indian trade with named individuals, and for many of the Indigenous people whose accounts were recorded, the two account books are the only known archival record in which they appear. Along with physical descriptions, Wendell and the Ulster trader at times described individuals in terms of their social relations with other Indigenous people, identifying family members of a new customer or noting the name of an existing customer who stood as a credit surety for a first-time customer. Wendell and the Ulster trader also noted social ties in the process of recording of debits and credits, as when siblings paid one another’s debts. As Native customers came and went with sometimes years between visits, recording these social ties helped identify individuals by placing them in their social context as Wendell and the Ulster trader understood it.2

I considered but ultimately decided against a geographically referenced network visualization for this piece because it didn’t seem like it would help advance my argument. First, there was relatively little geographic information in the data I was working with beyond national identification—I could have plotted Onondaga individuals to a central point within their historical territories, for example, but tying all individuals from a nation was less useful for the Ulster network of all Munsee individuals. Some Seneca accounts in the Wendell data had the town of their residence within Seneca territory, but not enough individuals had that level of geographic detail to make a geographically referenced network useful.

One of the historiographic questions on my mind writing this piece that the data did not let me pursue was the issue of how much contact Laurentian or “Canadian” Mohawks from St. Regis, Kahnawake, and other domicilé communities had with Confederacy Mohawk. Although Wendell had Laurentian and Confederacy Mohawk customers, his accounts did not note any connections between them.

The Haudenosaunee Five Nations include the Mohawk, Oneida, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Seneca, and after 1722, the Tuscarora (becoming known as the Six Nations), though Wendell’s Haudenosaunee customers included only individuals from the original Five Nations. In this article Haudenosaunee is used solely as a shorthand to refer to Five Nations groups rather than the broader Iroquoian cultural groups of Laurentian Iroquois or Mingoes of the Ohio Country, reflecting Wendell’s limited contact with those groups. With territories ranging from roughly modern Albany, New York in the east through southern Canada and modern Buffalo, New York in the west, the Six Nations had early and sustained contact with French, Dutch, German and English settlers along the frontiers of Iroquoia with a minimum of European settlement in core Haudenosaunee homelands until late in the eighteenth century. The relatively late encroachment of white settlement compared with the experience of other eastern Native groups resulted from a combination of Haudenosaunee political and military neutrality for much of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, advantageous geographic position, and shrewd diplomatic maneuvering, producing interconnected Native and non-Native communities along the frontiers of Iroquoia. The Wendell account book covers the period immediately proceeding and following the 1701 Treaty of Montreal and Haudenosaunee neutrality during Queen Anne’s War, reflecting a period of relative equilibrium in Iroquoia after several decades of war with New France and their Native allies.3

The significant number of women in the Wendell accountbook—half of all customers—indicates the safety of travel through Iroquoia facilitated by Haudenosaunee neutrality in early eighteenth century colonial conflicts. Haudenosaunee women’s place within their communities has been reassessed by a number of scholars in recent years, part of a broader realignment of the subfield of Haudenosaunee studies as a whole. The broad outlines of Haudenosaunee gender roles are familiar to many working in early American scholarship, with matrilineal, matrifocal extended family households which controlled agricultural production and influenced the consensus-based political life of the village. Clan mothers selected hereditary chiefs; female heads of household controlled land and food, distributing provisions to war parties; women’s councils called for peace and war; and matrons decided the fate of prisoners. The direct involvement of Haudenosaunee women outside the supposed domestic space of village and field has received renewed attention in recent years, with new studies suggesting that both Haudenosaunee women and men traveled frequently within and beyond Iroquoia, shaping the contours of contact with settler communities along the frontiers of Iroquoia to a much greater degree than previously thought.4 Although recent scholarship on Haudenosaunee women has shown their presence and significance beyond the village and clearing, there has been comparatively little reassessment of how women’s contacts reshaped diplomatic and quotidian interactions, or how Haudenosaunee women’s roles in these interactions differed from the intermarriage and métissage of the pays d'en haut or the tensely negotiated fictive kinship of the midcontinent.5

The Munsee to the south who traded at Ulster faced far greater colonial pressures. By one estimate, at the turn of the eighteenth century their population had fallen to 1000 to 1600 individuals, with only five percent of their homelands remaining unsold. Closer to expanding English populations, they also faced far pressure from expanding Euroamerican settlements, debt and dependence in colonial cash economies, and pressure from colonial governments which “used economic dependence as a tool of empire to force political capitulation.” Although the presence of Munsee customers trading at Ulster testifies to their continued presence in the face of land secessions and population pressures pushing their communities further inland, recent scholarship has pointed to a loss of political self determination by the early eighteenth century as Munsee communities struggled economically at the fringes of Dutch-Anglo settlement.6

Despite these pressures, Munsee women and ties through maternal kinship remained central to Munsee life well into the eighteenth century, with Munsee women continuing to serve as important economic actors and leaders. Like the Haudenosaunee, the Algonquian Munsee and broader Delaware culture groups were matrilineal, practicing gendered horticulture and seasonal subsistence rounds to complement increasing participation in colonial wage work and day labor. Munsee women’s “adaptive capacity” to work within and around the changing colonial system reinforced the importance of matrilineal kinship ties and networks of women. These ties were especially important at the household and family level, where Munsee women mediated ties between male leaders, maternal kinship ties remained essential to navigating community leadership, and women directed missionary efforts within their communities. The well-known rhetorical construction of the Delaware as metaphorical women by Haudenosaunee diplomats and others suggests a tension between rhetorical constructions of women as both marginal to formal diplomacy and central to the daily life of the community.7

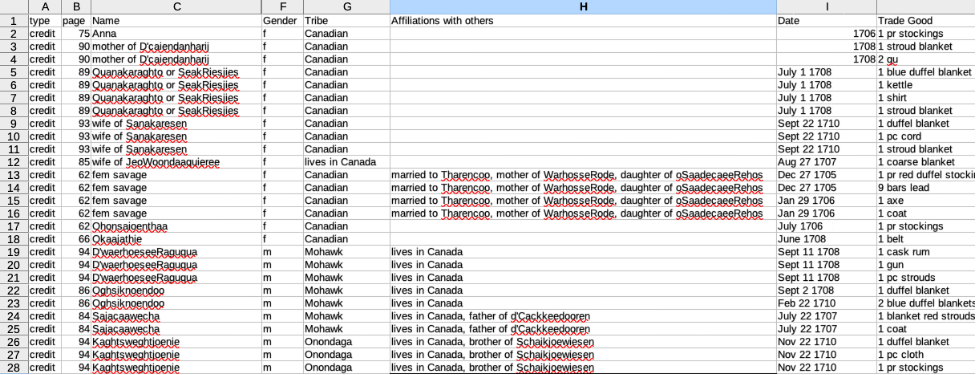

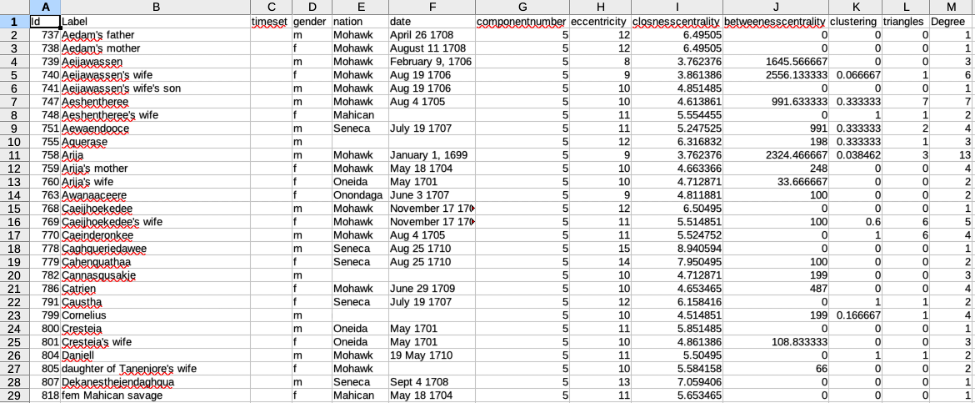

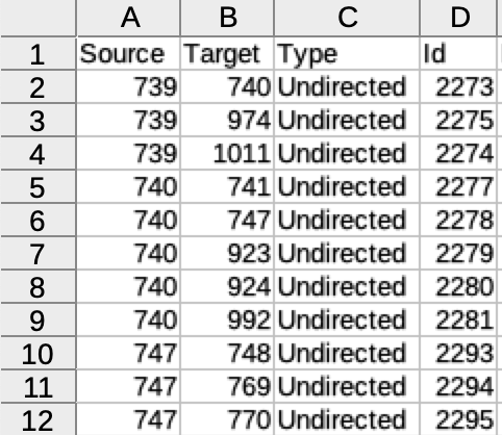

My initial interest in both account books was for the information about goods traded, so my transcription of the Wendell account book was structured to enable ease of counting goods and payments. Translating this to a network structure meant restructuring my data listing each exchange on an account (the first image below) into two relational tables listing descriptive information (the second image) and connections between individuals (the third image). Indigenous names were recorded with incredibly varied spelling, even when it was apparent the account was for the same person, so I opted to give each individual a unique identifying number. In my more recent work, I merge names with different spellings into one canonical name using OpenRefine for easier troubleshooting later in the workflow. This translation of exchange data into network data also required creating entries for individuals who were only implied in the data through their social relationships but didn't make purchases of their own.

The social ties that were recorded in these account books suggest that in early eighteenth century New York, Haudenosaunee women were perceived by colonists as bridges between intra-Haudenosaunee sub-communities, while Munsee women were perceived by colonial observers as pushed to the margins of their communities. Cultural differences between the Haudenosaunee and the Algonquian Munsee and the idiosyncracies of the individual traders of course cannot be discounted, but the two contemporaneous, geographically proximate networks presented here were documented through similar Anglo-Dutch credit processes and yet differ greatly in their gendered structure. In the economic snapshots provided by the two account books, Haudenosaunee and Munsee women shared striking similarities and a few key differences. In both cases, women participated in about half of all accounts—that is, half of all accounts included at least one woman making purchases under her own name or that of a male account holder, often her husband or other male relative. In both the Wendell and Ulster account books, women were the sole account holder on about twenty percent of all accounts. And yet Haudenosaunee and Munsee purchases differed in important ways: where Haudenosaunee customers mainly purchased cloth (53.8% of all purchases) and paid debts with peltry, Munsee customers also bought cloth, but at rates roughly comparable with alcohol and ammunition (35.5%, 29.2% and 23.2%, respectively), and paid debts with cash and day labor. Additionally, while purchases of food were not a significant proportion of purchases by Munsee customers—only 2.9%—Haudenosaunee customers made almost no food purchases. This suggests that Munsee customers were much more deeply entangled in and at times dependent upon participation in colonial labor systems, and while Haudenosaunee customers participated in the fur trade, they did so without the more direct, daily colonial entanglement of day labor and were less reliant for basic necessities like food.8

The difference between the structure of Haudenosaunee and Munsee social networks which Wendell and the Ulster trader envisioned despite similarities in women’s rate of participation and roles within their communities suggests that imagined marginalization of Indigenous women was part of settler colonialism’s cycle of displacement, erasure, and replacement. Alongside the more direct colonialist pressures of land dispossession, debt, and economic dependence, Munsee women were seen through the colonial lens to be less influential in their own communities. Whether Munsee women were in lived reality pushed to the margins of their communities while Haudenosaunee women functioned as bridges between subcommunities is not determinable from network structure alone—though recent scholarship suggests that Munsee women were not marginalized any more than Haudenosaunee women. Rather, the contrasting network structures here illustrate the process of settler colonial erasure as it was inscribed, in the perceived attenuation of Indigenous social ties.9

The status of Indigenous family structures has been used in the scholarship of Native history as a barometer of colonialism—large, matrilocal extended families taken as indicators of strong self determination, while nuclear single family households have been held up as evidence of colonialism and loss of Indigenous kin networks. Declensionist narratives, which chart the inevitable triumph of settler colonial groups, have recently come under renewed scrutiny in early American history, but without a corresponding re-evaluation of Native women’s roles within their communities. Scholars of Indigenous and early American studies are well aware of the problems of inscribing European categories on Native groups, and this problem is compounded in the study of Native women who were archivally erased because they were perceived by Europeans as inherently non-public and therefore outside the sphere of diplomatic activities copiously documented in frontier interactions. Individual Native women are comparatively much more visible in genres of documents like account books in which these Anglophone divisions of public and private had not yet firmly taken hold.10

The Problem and Potential of Tiny Data

The Indigenous social networks analyzed here were built using digital humanities methods which reveal the limits of the settler colonial archive for documenting Indigenous social ties. Indigenous histories of every kind, traditional and digital both, face the problem of tiny data. Digital humanities methods have been pioneered to deal with “big data,” or at least medium data, the massive availability of text and metadata made possible by digitization of social life and physical archival media. One of these methods, social network analysis, models relationships between individuals to reveal the broader structure of those social relationships. For humanistic study of the past, social network analysis can be used to examine social phenomena, community formation, and influence.11

This article was prompted in large part as a response to Robert Michael

Morrissey’s two articles “Archives of Connection” and “Kaskaskia Social

Network.” Although I was working on similar issues, with similar

evidence, and in the same historical period, I don’t believe it’s always

possible to reconstruct the kind of whole-network that Morrissey was

able to reconstruct for Kaskaskia due to limitations of evidence. In

attempting to see if I could reconstruct a similar whole-network with

the evidence available to me, I had to work through what I was able to

discern from a partial network.

Robert Michael Morrissey, “Kaskaskia Social Network: Kinship and

Assimilation in the French-Illinois Borderlands, 1695–1735,” The

William and Mary Quarterly 70, no. 1 (2013): 103–46,

https://doi.org/10.5309/willmaryquar.70.1.0103;

Robert Michael Morrissey, “Archives of Connection,” Historical Methods:

A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 48, no. 2

(2015): 67–79.

In the case of in Indigenous histories with necessarily tiny data, these methods of analyzing patterns in large, well-documented networks will never reveal the same sort of patterns because the documentation to encompass a full recreation of all social ties simply does not exist. However, this method of examining networks can be turned around to examine the creation of silence in the archive itself and the implication of this silence for the study of Indigenous kinship. The example presented here is intended to offer a demonstration of the promise and peril of digital humanities broadly in the study of groups which did not leave copious written records to be digitized, by examining the limitations and potential of one methodological approach. By building the partial networks visible in the settler colonial archive, it is possible to make visible the limits of settler views of Indigenous social life. A partial network does not reveal which individuals were most influential or central, but which individuals were perceived to be so from the perspective of those documenting the interactions. For the study of Indigenous kinship ties, this means that a partial network can reveal the visibility of influence to European observers.

Archival silences are a problem well known to scholars, who must routinely work around the limitations of incomplete records, the deliberate or non-deliberate omission of information, and the loss or exclusion of documents from the archive. All of these points of silencing are important for traditional history, but doubly so for relatively new digital humanities methods, which rely on massive amounts of digitized text and data, to analyze the past from a new angle. Recent efforts to digitize and make publicly available print text has massively increased the amount of data for digital humanities scholars to work with, but for Indigenous history, print and textual epistemology often doesn't fully encompass Indigenous communities, if at all. As Adeline Koh, Roopika Risam and others have argued, digital humanities methods' reliance on the massive availability of print material without a corresponding retheorization of the settler colonial archive has the potential to recenter elite white and male subjects.12

The last several decades of ethnohistory have honed techniques for working within the limits of the archive, by reading against the grain of archival records, reading for the agency of Indigenous people, and centering the cultural and social contexts of Native actors. This approach rests at least in part on the belief that Indigenous social life can be reconstructed from the settler colonial archive. While great strides have been made to incorporate archaeology, anthropology, linguistics, religion and cultural practice into the reframing of textual records, the knowability of archivally marginalized groups is both epistemology and agnotology, a non-neutral product of colonialism, imperialism and slavery. The study of colonialist historical memory and historiography examines this process after the moment of encounter has passed or as the first draft of history, rather than the process of erasure during the moment of culture contact and documentation. These archival silences have been long recognized in the field, but they often remain static moments of loss rather than active moments of erasure, part of the colonialist process and the product of many historical choices.13

One potential approach to the problem of tiny data in the settler colonial archive is to use digital methods to examine, foreground and analyze the creation of silences as products of colonialism which must be confronted, as Amy Den Ouden calls for, in an anti-colonial critique of objectivist colonial histories which accept and recreate the settler colonial frame. In the case of reconstructing Indigenous kinship and social ties through the lens of the settler colonial archive, social network analysis might be most useful in exposing the limits of settler views into Indigenous social life and the ways in which these limits have shaped the archival and historiographical erasure of Indigenous women.14

Methods and Approach

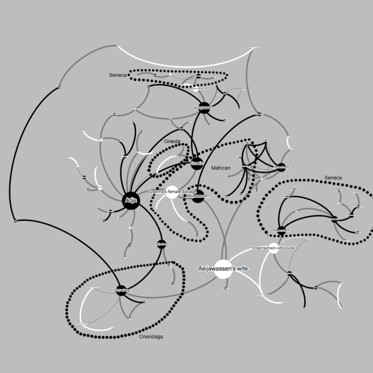

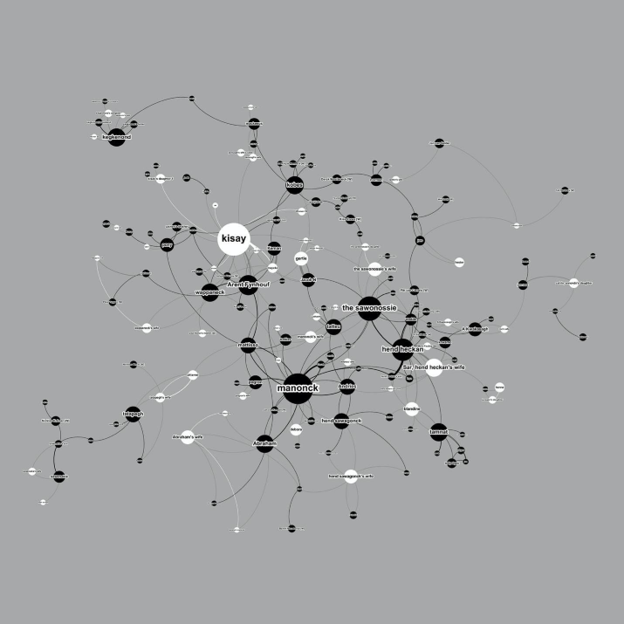

In the two networks examined here, each network is laid out in a force atlas layout, which tends to cluster individuals with densest ties to one another and spread out very influential hub individuals with little connection to one another. Depending on the density of the connections, individuals are clustered together or visually spread apart to give a broader overview of the network as a whole. The physical layout of each network is not related to geography or time; the proximity of individuals to one another is determined by their ties to others, and the density of their connections' connection to others, though any given individual may not be directly connected to a neighboring individual, having been pulled by connections to more distant individuals away from their nearer direct connections.

The size of each individual in each network is scaled according to the measure of their betweenness centrality as a stand in for perception of their social influence. An individual with a high betweenness centrality is on the shortest path between many others in the network, while an individual with a low betweenness centrality is marginal to their network because they do not connect their neighbors to the shortest path to others. Betweenness centrality therefore stands in for influence not by the number of connections a person has, but the importance of those connections to the wider network—a measure of the key player in, for this instance, Six Degrees of Canowaacightuea. If one individual knows many people, but none of them are connected to anyone else, that person is still a very small, uninfluential dot, but if the people one individual knows are connected to many other people, that makes the individual a bigger dot and a more influential part of their network. For studying Indigenous kinship ties, this betweenness centrality measure of influence is particularly important because it lets us see how visible Native ties within their own communities were to European observers.

The question of how and how many Haudenosaunee people lived and traveled in territories of nations other than the one of their birth is one of the major historiographic questions for the subfield of Iroquois studies. I was hoping to be able to track this question through a georeferenced network for this article, but the number of individuals with residence mentioned were too small to make a georeferenced network worthwhile for this piece.

Gender and nationality in each network was determined by the description given within the document. In many cases, individuals were described at least once with their tribal origin or place of residence, such as Saakadesendee, a Mohawk “who lives in Seneca country.” The few individuals such as these who were noted as residing in other territories were tracked as their nation of origin; in the case of Saakadesendee, Mohawk. If the account book did not note a different nationality for family members, individuals were assumed to be of the same national origin as their explicitly noted familial connections, and connections between individuals of different national origin are therefore connections noted within the document itself. Although Haudenosaunee family ties could and did cross national boundaries and intra-Haudenosaunee clan affiliation was an important social organizer, Wendell’s understanding of Haudenosaunee national identity shaped how he recorded intra-Haudenosaunee ties, and it is that perception which is analyzed here.

For determining gender, explicit descriptions within the document were likewise used. In cases such as this where an individual was identified by a single common name, such as the many Gesinas, Seths, Hendricks, and Alidas, each instance of that name was given a unique number and tracked as a separate individual, therefore likely underestimating the number of connections. In the account books, the traders frequently referred to Native customers by epithets and descriptors such as “the big pockmarked female” or “has a scar on her head from a cut,” descriptions which were used for the same individual across several interactions sometimes spanning years. The traders also occasionally noted that an otherwise undescribed customer had purchased and item “for her son” or other relation, or made a note that the customer “must pay the remainder to her when she brings the coat.” The traders also frequently defined individuals through their connections to others. For example, when Kadaroonichthae paid a debt of one beaver pelt with its worth in wampum, the trader did not record her gender or use pronouns to define her. He did, however, describer her as the “mother of Nansendagqua’s wife,” making it possible to both assign her a gender and place her in relation to others in the network.15

Women like Nansendagqua’s wife, “the pockmarked female,” and Canowaacightuea are like many other Indigenous women in the archives of early America: rarely identified by their own names, identified by their affiliation with male kin if at all, often caricatured, and rarely visible in more than one archival source, effectively erasing them as autonomous individuals. Canowaacightuea’s other kinship ties, her social connections beyond the brief glimpse in 1704, are not unknowable but they are unrecorded as a part of settler colonialism’s erasure and replacement of Indigenous people. Unlike other mixed Indigenous-settler communities which have been analyzed recently with social network analysis, the Native communities examined here simply were not documented as extensively in written records of any kind because they were not integrated as fully in the settler community producing the documentation. Especially for the study of Indigenous networks, the available documentation is not only incomplete but often elides social ties beyond the view of colonial record keepers; the ties recorded were by definition only those made visible within the extent of a colonial sphere of influence, which may not have encompassed the total lived experience of Indigenous people.16

For communities for which this full documentation does not exist, social network analysis may be more useful in analyzing how and why Indigenous social ties were documented in the settler colonial archive and what that says about the visibility of Indigenous social ties to settlers, rather than reconstructing and analyzing the social ties themselves. These partial networks, and the settler colonial view of Indigenous kinship networks which they capture, expose the limits of documentability itself for understanding Indigenous social ties through the settler colonial archive. The networks compared here, because they are built from contemporary account books with very similar recording practices, suggest the ways in which Native women were erased as influential parts of their kinship networks in the process of documentation. These partial networks are therefore a representation of settlers' perceptions of Indigenous kinship and social ties rather than a full reconstruction of those ties.

| Network | # of connected individuals | # of connections | Average density of connections 17 | Network diameter 18 | Average clustering coefficient 19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wendell 1696-1726 | 102 | 127 | .025 | 15 | .284 |

| Ulster 1712-1732 | 162 | 260 | .018 | 14 | .332 |

Wendell Network 1696-1726

The Wendell network is built from the account book of Albany-area Dutch trader Evert Wendell, kept as a ledger of debts and purchases by mainly Haudenosaunee customers from 1696 to 1726. A small handful of non-Haudenosaunee Native customers in the network, likely Mahican, were probably resident very close to Albany and the Wendell family, as suggested by their occasional payment of debts with day labor or Wendell’s description of them as a family member’s servant, but the majority of the Native people in this network traveled from their own homes in what is now western New York or southern Canada to do business with Wendell in Albany. Very few of these Native people were recorded in any other documentary sources, so the view of their social ties within their own communities was limited to what Wendell observed himself or was told about.20

Wendell’s recording of these economic and kinship ties was in tension with his perception of Native women as peripheral to their male relations, especially in the case of women who Wendell did not name except to define them by their relationships to others. Although Wendell left many more female than male customers unnamed, thereby erasing them as independent individuals, he nonetheless recorded their influence within their communities in the very act of describing them in relation to others. Wendell himself assessed Indigenous women like “the Pock-marked Squaw [sic],” “the squaw [sic] brought by Groetie,” or “Aeijewassen’s wife” as uninfluential in their social ties, rarely defining men solely through their relations to others. Although men were occasionally described through their relationships with others, it was more often through their ties to other men. Out of the more than one hundred individuals in the network, only four men were identified only by their connections to women, and those women were themselves just as often unnamed. The Mohawk men Caaheghtsiedawee, who was identified as “married to daughter of Tanenjores’s wife,” or Caghneghjakoo, the “son of Cattquierhoo’s wife,” were identified first by their connection to a woman, but those women themselves were unnamed and identified by their husband’s names. Wendell very often did business with a man’s wife, mother, or sister; very rarely did he do business with a woman’s husband or brother.21

Even as Wendell rhetorically erased these Indigenous women’s social individuality, his interactions with them continually emphasized their influence within their networks. Dutch women were not subsumed under their husbands' legal identities as under English coverture, and ethnically Dutch residents of English New York like Wendell had not yet shifted to English inheritance practices in the early eighteenth century. Wendell maintained separate accounts for husbands and wives and some of his largest and longest-running accounts were with women, even women who he identified only by their relation to their husbands. Despite Wendell’s rhetorical erasure of some of his female customers, his accounts nonetheless reveal parity between the influence of Native women and men.22

The choice to exclude Evert Wendell and the unnamed trader in the Ulster network from the networks they recorded was one of the things I was most uncomfortable about from a methodological perspective when writing this piece. In the end, I feel it was the right choice because it helped foreground the main question of Indigenous peoples' connections to one another but it does underline the reality of the network as a constructed artifact.

The Wendell account book includes one main network and several unconnected smaller networks. The smaller networks included two to ten individuals, often identified by Wendell as natal or marital relations from a single tribal background. These smaller networks have been excluded from the visualization presented here. In theory, every Native person recorded in the Wendell account book could be connected to every other Native person through their connection to Wendell. This “ego network” structure would disproportionately represent Wendell himself as the most influential and connected person in the network, rather than representing the network as it was made visible to Wendell. Wendell, as well as his sister, brother, and mother, who also recorded some sales to Native customers, have therefore been excluded from this network.23

The technical limitations of the journal, which required black and white images for the print edition at the time this was submitted, limited the visualizations for this piece in many ways. I find network visualizations with, in this instance, nationality marked by node color much easier to read. This visualization is very “noisy” because it tries to communicate too much information about both nationality, gender, and gendered connections all at once. If I were to do the visualizations for this piece again, I would visualize the network in D3.js and produce multiple images for nationality, gender, and gendered connections.

This network visualization is slightly different than the final published version. In both this and the later Ulster network visualization, I originally submitted network visualizations with curved edges out of aesthetic preference, but in later revisions of the networks I found that straight edges and more closely clustered nodes (a setting of the force atlas algorithm used for generating layout) made a network that was more "readable" in print format. Since writing this piece, I've switched from using Gephi for analysis and visualization to using Python NetworkX for analysis and D3.js for visualization, but my preference with both work flows in the writing and drafting stages is very sparse networks where the individual connections are more visible to me as I'm writing, and in the publication stage my preference is for more densely clustered networks. My greatest preference for network visualization is for an interactive format where the reader is not so dependent on my choice of a single image to understand the network structure, but that is often not an option, and even in interactive formats, the initial visualization needs to be understandable without excess visual clutter or confusion.

The issue of visualizing mixed-gender connections is the one I am the most dissatisfied with in this piece and in my ongoing scholarship in this vein. Women’s roles as intra-Indigenous and cross-cultural mediators is one of the major questions of the subfield, but I have not yet found a methodological approach with network analysis that either quantifies or visualizes mixed-gender edges in a satisfactory way.

In the largest Wendell network, although women make up slightly less than half of the individuals documented in the network and in the account book, the median measure of women’s influence and men’s influence is the same. That is, those women who were visible through the lens of Wendell’s trade were just as influential as the visible men. From Wendell’s limited perspective in Albany, filtered through his limited view of his Native customers' lives and filtered through his own rhetorical erasure of women’s separate identities, there was no substantial difference in this network between the visibility of women’s influence and the visibility of men’s influence. Most significantly, as connectors between tribal subnetworks within the main network, otherwise nameless women appear as influential ties holding the network together. “Susanna’s female savage,” “Aeijawassen’s wife,” and “Oneghriedhaa’s wife’s sister” have very small accounts of their own or appear only on the accounts of others, but the frequency of their appearance with others places them as central figures binding the main network together.

Influential men in this network are prominent in the Wendell account book both because they held large accounts with Wendell and because they had many ties to other Native people. As represented by their degree, or number of connections to others, men in the Wendell account book who visited Albany frequently and bought large quantities of merchandise appear much more influential than any women in the network. However, these men’s connections were often unconnected to any other person in the network, making them essentially dead ends for social influence (at least from Wendell’s vantage point). Judged only on degree, or the number of people they were connected to, Native men appear as central hubs of connection between otherwise unconnected individuals. However, as judged by their betweenness centrality, or their connections to others who are connected others and their role as a short path between individuals, these men who held large accounts with Wendell become as prominent as unnamed women like “Susanna’s female savage” or “Aeijawassen’s wife” who held relatively small accounts. Individuals with higher betweenness centrality bind a network together and form the central, shortest paths between most individuals. Although these women were rhetorically erased by Wendell as independent individuals, in the process of defining them through their relationships with others, he also recorded their central importance in connecting their communities.

Not only did these women form the central connections through their communities, they also bridged otherwise unconnected tribal subnetworks. The Mohawk women “Aeijewassen’s wife,” “Oneghriedhaa’s wife’s sister,” and Kadaroonichthae as well as the Mahican woman “Susanna’s female savage” all bridged a subnetwork of their own nation with a connection to a Native man of another Haudenosaunee nation. While men therefore also served as bridges between tribal subnetworks, men who served as inter-tribal bridges tended to have no other connection to the main network, while the women they were connected to had many other connections in the main network. Some men, like the Mohawk Arija and the Mahican Groetie also had inter-tribal connections to other men, but the men of other nations they were connected to tended to have additional connections to the main network. Women therefore had the unique position in this network of serving as the sole bridge between tribal subnetworks.

Whether this phenomenon is due to actual patterns of Native kinship ties or due to the limits of Wendell’s perspective on the network is unclear. Whatever the case, it does suggest that Haudenosaunee women had far greater range of movement and connection outside their home communities than previously recognized. Indigenous women, whether actually or only functionally from a European perspective, acted as primary connectors and bridges between Indigenous communities in this network despite Wendell’s rhetorical erasure of many Indigenous women as individuals. As a small glimpse of kinship ties between Haudenosaunee and Mahican individuals who traded at Albany, this network suggests that the lived experience of culture contact depended in much greater degree on the presence and activity of Indigenous women than Wendell and other settler colonial rhetorical erasure of them would suggest.

Ulster Network 1712-1732

Figure 3:

Ulster network, 1712-1723. White nodes are female and black nodes are male. Connections are colored by the gender of individuals connected: a white edge connects two women; a black edge connects two men; a gray edge connects a woman and a man.

Figure 3. Ulster network, 1712-1723. White nodes are female and black nodes are male. Connections are colored by the gender of individuals connected: a white edge connects two women; a black edge connects two men; a gray edge connects a woman and a man.

The Ulster network is roughly contemporaneous with the Wendell network, and is built from an account book kept by an anonymous Dutch trader in Ulster County New York between 1712 and 1732. The patterns of trade between the anonymous Dutch trader and his Esopus, Wappinger and Munsee Indian customers, as well as the cultural and colonial differences with the Haudenosaunee customers documented in the Wendell account book which these patterns suggest, have been discussed in the annotated translation of the Ulster account book. The relationships documented in the Ulster account book were of the same kind as those documented in the Wendell account book, which were a mixture of kinship and economic ties documented when family members paid debts, made purchases, or were used by the Dutch trader to identify otherwise unnamed customers. As in the Wendell account book, these unnamed customers identified by their kinship connections were mainly women. The anonymous Dutch trader has also been excluded from the network for reasons discussed above.24

As a contemporaneous network documented in a similar manner to the Wendell network, the Ulster network offers some suggestions for understanding how the settler colonial views of these networks were shaped by social factors. Although the Algonquian Munsee differed culturally from the Haudenosaunee, they shared a matrilineal and matrifocal kinship structure, as well as a common, if contested, vocabulary of gendered kinship diplomatic metaphors. Women appear as account holders and transacting business on others' accounts at roughly similar rates in the Wendell and Ulster account books, but Munsee women in the Ulster network are much less influential on average and function less frequently as bridges or hubs. With the exception of Kisay, a woman who appears as the center of a very active kinship subnetwork, the most influential Munsee women in the Ulster network appear alongside their more influential husbands.25

Kisay’s prominence in the Ulster network was genuinely shocking when I first constructed both of these networks. A traditional close reading of her account, which was longer lasting and included many more purchases than most other individuals in her network, suggested that she would be prominent. However, economic prominence did not always map onto social prominence in either the Wendell or Ulster networks, so her connection to so many other individuals and her significance was only apparent with social network analysis.

Kisay’s husband Arent Fynhout also appears as one of the more influential members of the network, but less influential than Kisay herself. As an exception to the general pattern of more influential husbands and less influential wives in the Ulster network, Kisay and Arent Fynhout offer an interesting counterpoint to the influence of Haudenosaunee women documented in the Wendell network. Kisay traded on her own account, her husband’s account, and the accounts of others, and the Dutch trader identified other Native people by reference to her much more frequently than by reference to her husband. She is also one of only two women in this network who were used as reference points for male kin. Kisay and another much less prominent woman Kegkenond were used to identify daughters, fathers, husbands, sisters, and daughters' husbands who were otherwise unnamed, while other named and unnamed Munsee men were identified by their connections to other men. Other influential Native women in this network appear as adjuncts on their husbands' accounts, and were documented with many fewer connections independent of their husbands' connections. Whether Kisay’s prominence in this network was due to her own social capital, her large number of kin, or some other factor is unclear, but she stands out starkly as the exception to the general pattern of women’s much lower influence in the Ulster network compared to the Wendell network.26

Munsee women’s comparative lower influence is due in part to the structure of the network, which features a large central component with few subcommunities to be bridged. The lower average density of this network compared to the Wendell network belies the density of connections in the main cluster of the network. (See Table One) Whereas the Wendell network is composed of interconnected hubs, the main component of the Ulster network reveals dense connections between the main hubs of the subnetworks centered on Kisay, Manonck, the Sawonossie, and Hendrick Heckan. The Munsee, Esopus and Wappinger individuals who purchased from the anonymous Dutch trader in the Ulster account book performed day labor and defaulted on their debts at much higher rate than did Evert Wendell’s Haudenosaunee customers, an indication of the greater impact of settler colonialism and reorientation of Native labor patterns for Munsee people in the lower Hudson than in Iroquoia.27

The structure of the Wendell and Ulster networks also suggest corresponding limitations to settler colonial views of Indigenous kinship ties. In the Wendell network, a few key figures served as gatekeepers to European knowledge of Haudenosaunee kinship ties, as indicated by the hub and bridge structure of the Wendell network with several influential women included as hubs. The Ulster network, with its more densely connected subnetworks, suggests that the Ulster trader had fuller knowledge of connections between his Munsee customers, or at least more frequently observed connections between them than did Wendell. Though a few women such as Pitternel and Gertie function as bridges in the Ulster network, men much more frequently occupy the role of bridge between subnetworks, and the circular nature of the dense connections in the Ulster network suggest that the anonymous Dutch trader’s view of his customers' kinship and social ties was much less mediated than was Wendell’s.

As the Munsee were incorporated more fully into settler colonial economic structures of debt and day labor, their kinship ties were made more visible to the settler colonial archive as well. The difference in the gendered structure of the roughly contemporary Haudenosaunee Wendell network and Munsee Ulster network, documented in similar ways, suggest that broader forces of economic and social colonialism shaped both Indigenous kinship ties and settler colonial views of them. The greater rate of debt default and daylabor among the Munsee, coupled with the denser structure of the network and women’s less prominent place within it, suggests a correspondence between the invisibility of Native women and the visibility of Indigenous networks in the settler colonial archive. Although at first glance paradoxical, the decreasing visibility of Native women as their kin and social networks became more visible is the process of archival erasure as a product of colonialism.

The work for this project began as an attempt to simply keep track of who was related to who, but as the connections multiplied it became clear that Wendell and the Ulster trader saw the individuals they traded with as deeply enmeshed in their social context, at times even inseparable from their social context because of the need to identify individuals by their relationships. Social network analysis, with its utility to zoom out and examine the network as a whole, seemed at first blush the perfect fit for this accumulation of individual connections. However, digital humanities methods, like traditional historical and ethnohistorical methods, rely on a limited settler colonial archive. As a way of analyzing and critiquing the limits of the archive itself and the utility of the settler colonial archive as a site of study for Indigenous kinship ties, social network analysis might be one mode of reading against the grain in ways made familiar by ethnohistorians. Networks of necessarily tiny data do not reveal the complete structures of Indigenous kinship networks, but rather the parts of those networks made visible to settlers and the ways in which colonialism shaped the perception of Indigenous social ties.

The nearly contemporaneous eighteenth century Wendell and Ulster networks suggest that European access to and therefore the archival visibility of Indigenous social ties was both a symptom and byproduct of colonialism. Cultural, social and economic factors may account for differences in the structural role of women and purchasing patterns which brought Indigenous peoples into contact with the Dutch traders who documented their kinship ties. The Munsee, integrated into Anglo-Dutch economic networks by debt and day labor to a much greater extent than the contemporary Haudenosaunee, had much more dense social ties documented through the process of their exchange with the Ulster trader. The process of colonialism which brought Munsee and Haudenosaunee families into economic contact with Dutch traders made their kinship ties more or less visible. Structurally, these two contemporary networks reveal cultural differences in the role of Native women tying together Indigenous kinship networks, with Haudenosaunee women functioning both as hubs of clusters and as bridges between clusters, where Munsee women remained on the edges of their relatively dense subnetworks and ties between men bridged clusters.

Haudenosaunee women’s roles as bridges between inter-tribal sub-communities has been under recognized because of the process of archival erasure which constructed women as non-public actors. Women’s roles in bridging communities took place in small scale, economic, social, and fictive kinship interactions rather than the more archivally visible and masculine-coded diplomatic encounter. These connections along the borders of Native and settler communities, as well as Native women’s and couples' roles as go-betweens in the context of exchanges suggests that Haudenosaunee women played a role in defining the social borders of their communities in ways elided by the model of male intercultural brokers or Native women’s fur trade intermarriages.

Colonial perceptions of Indigenous women’s roles within their own communities suggests the limits of the settler colonial archive for documenting the role of Indigenous women in their own families, revealing both the colonialist epistemology and agnotology of Indigenous kinship ties. Settler colonial perceptions of gender roles defined Indigenous women through their male relations if acknowledging their presence at all, limiting the archival documentation of Indigenous kinship ties through a process of gradual erasure as Indigenous networks became more visible to settler colonial view. The structure of Haudenosaunee and Munsee social networks as recorded by Wendell and the Ulster trader suggests that colonial observers perceived Indigenous women as less influential within communities more deeply entangled in colonial labor systems. While Haudenosaunee women were perceived as bridges between sub-communities which operated mainly outside the sphere of settler observation, Munsee women were perceived as marginalized within their own communities as their communities lost political and economic self-determination. Indigenous women’s supposed declining status and influence under colonialism may therefore be as much part of the colonial archival process as a product of colonial restructuring of lived experience.

-

Evert Wendell, Kees-Jan Waterman, and Gunther Michelson, “To Do Justice to Him & Myself”: Evert Wendell’s Account Book of the Fur Trade with Indians in Albany, New York, 1695-1726 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2008), 36. ↩︎

-

For further discussion of the context and significance of the two account books, as well as notes regarding Indigenous individuals who do appear in other known records, see the published version of each. Evert Wendell, Kees-Jan Waterman, and Gunther Michelson, “To Do Justice to Him & Myself”: Evert Wendell’s Account Book of the Fur Trade with Indians in Albany, New York, 1695-1726 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2008); Kees-Jan Waterman, and J. Michael Smith. Munsee Indian Trade in Ulster County, New York, 1712-1732. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 2013. ↩︎

-

Jon Parmenter, The Edge of the Woods: Iroquoia 1534-1701 (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2010), 257-266, 271-273; Matthew Dennis, Cultivating a Landscape of Peace : Iroquois-European Encounters in Seventeenth-Century America (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1993); David Preston, The Texture of Contact: European and Indian Settler Communities on the Frontiers of Iroquoia, 1667-1783 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 23-26; Gail D MacLeitch, Imperial Entanglements: Iroquois Change and Persistence on the Frontiers of Empire (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011); Daniel K. Richter, The Ordeal of the Longhouse: The Peoples of the Iroquois League in the Era of European Colonization. (Chapel Hill: Published for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, by the University of North Carolina Press), 1992, 214-235; Richard Aquila, The Iroquois Restoration: Iroquois Diplomacy on the Colonial Frontier, 1701-1754. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1983, 23-25. ↩︎

-

For an overview of the recent shifts in Iroquois studies both generally and with regard to women’s roles, see Edward Countryman, “Toward a Different Iroquois History,” The William and Mary Quarterly 69, no. 2 (2012): 249–353. For an overview of the traditional assessment of Iroquois women’s political and familial roles, see Bonvillain 53-57 and Elisabeth Tooker, “Women in Iroquois Society,” in Extending the Rafters, 1984; Barbara Alice Mann, Iroquoian Women: The Gantowisas (New York: P Lang, 2000). For a critique of the “mothers of the nation” framework with Iroquois women’s roles limited to largely symbolic care work rather than direct involvement in governance, see Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 148; Audra Simpson, “Seven Generations of Iroquois Leadership: The Six Nations Since 1800 (review),” The American Indian Quarterly 34, no. 2 (2010): 274–79. For the “village and clearing” model of Iroquois women limited to homes and fields, see, for example, Daniel K. Richter, Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001), 5; José António Brandão, Your Fyre Shall Burn No More : Iroquois Policy toward New France and Its Native Allies to 1701 (Lincoln Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), 1 and 65; Tooker, “Women in Iroquois Society”; Anthony Wayne Wonderley and Hope Emily Allen, Oneida Iroquois Folklore, Myth, and History: New York Oral Narrative from the Notes of H.E. Allen and Others (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 2004), 7–8; William N. Fenton and Elisabeth Tooker, “Mohawk,” in Handbook of North American Indians, ed. William C Sturtevant (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1978), 466–80; Judith K. Brown, “Economic Organization and the Position of Women among the Iroquois,” Ethnohistory 17, no. 3/4 (1970): 151–67. This model has persisted despite several decades of critique. For critiques of the village and clearing framework, see Nancy Shoemaker, “The Rise or Fall of Iroquois Women,” Journal of Women’s History, 1991, 39–57; Devon A Mihesuah, “Commonalty of Difference: American Indian Women and History,” American Indian Quarterly 20, no. 1 (1996): 15–27; Jo-Anne Fiske, “By, For, or about?: Shifting Directions in the Representations of Aboriginal Women,” Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture and Social Justice 25, no. 1 (2000): 12–13. ↩︎

-

Michele Mitchell, “Turns of the Kaleidoscope: ‘Race,’ Ethnicity, and Analytical Patterns in American Women’s and Gender History,” Journal of Women’s History 25, no. 4 (2013): 46–73; Robert Michael Morrissey, “Kaskaskia Social Network: Kinship and Assimilation in the French-Illinois Borderlands, 1695-1735,” William and Mary Quarterly 70, no. 1 (2013): 103–46; Brenda Macdougall, “Speaking of Metis: Reading Family Life into Colonial Records,” Ethnohistory 61, no. 1 (2014): 27–56. For one case of a female diplomatic broker in eighteenth century Iroquoia, sometimes figured as exceptional rather than exemplary in the broader scholarly conversation, see Jon Parmenter, “Isabel Montour: Cultural Broker on the Frontiers of New York and Pennsylvania,” in The Human Tradition in Colonial America, ed. Ian Kenneth Steele and Nancy L Rhoden (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1999), 141–59; Alison Duncan Hirsch, “‘The Celebrated Madame Montour’: ‘Interpretress’ Across Early American Frontiers,” Explorations in Early American Culture 4 (2000): 81–112. ↩︎

-

This article follows the published version of the Ulster accountbook and other works in the use of Munsee as a cultural group related but distinct from the broader Delaware or Leni Lenape of southern New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania, although the historic term Munsee was not used until 1727. See Waterman and Smith, 36n4; Jane T. Merritt, At the Crossroads: Indians and Empires on a Mid-Atlantic Frontier. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003, 31-32 n13; Jane T. Merritt, “Cultural Encounters along a Gender Frontier: Mahican, Delaware, and German Women in Eighteenth-Century Pennsylvania.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 67, no. 4 (2000): 502–31; J. Michael Smith, “The Seventeenth Century Sachems of the Wapping Country: Ethnic Identity and Interaction in the Hudson River Valley,” in The Journey: An Algonquian Peoples Seminar, Selected Research Papers, 2003-2004, ed Shirley W Dunn (Albany: New York State Musem, 2009), 39-67. For a differing interpretation, see Marshall J. Becker, “Lenopi; Or, What’s in a Name? Interpreting the Evidence for Cultural Boundaries in the Lower Delaware Valley,” Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of New Jersey, no. 63 (2008): 11-32. For the presence of Munsee communities in the lower Hudson Valley region, see Waterman and Smith, 9-11 and 39n24-25; Paul Otto, The Dutch-Munsee Encounter in America: The Struggle for Sovereignty in the Hudson Valley. New York: Berghahn Books, 2006, 18; Herbert C. Kraft, The Lenape-Delaware Indian Heritage: 10,000 BC to AD 2000 (Stanhope, NJ: Lenape Books, 2001) 428-429, 440; James D Folts, “The Westward Migration of the Munsee Indians in the Eighteenth Century,” in The Challenge: An Algonquian Peoples Seminar, ed. Shirley W Dunn (Albany: New York State Museum, 2005), 34. For Munsee population and colonial pressures, see Robert S. Grumet, First Manhattans: A History of the Indians of Greater New York. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011, 164-165; Robert S. Grumet, The Munsee Indians: A History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009, 208-213; Otto, 163-164, 175-176. For quote, see Merrit 2003, 53. ↩︎

-

For women’s changing roles among the Delaware of Pennsylvania, see Merritt, 2003, 51, 53-56, 74-75, 131, 143-144, 151-156; Merritt, 2000: 502–31; Gunlög Fur, A Nation of Women: Gender and Colonial Encounters Among the Delaware Indians. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012, 4-5, 18-20 and 107-127 passim for Moravian missionaries' use of and anxiety regarding Delaware women’s kinship networks. On Munsee women’s roles, see Robert S. Grumet, “That Their Issue Be Not Spurious: An Inquiry into Munsee Matriliny,” Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of New Jersey 45 (1990): 22; Robert Grumet, “Sunksquaws, Shamans, and Tradeswomen: Middle Atlantic Coastal Algonkian Women during the 17th and 18th Centuries.” In Women and Colonization: Anthropological Perspectives, edited by Mona Etienne and Eleanor Burke Leacock. New York: Praeger, 1980; Otto, 15; Grumet 2009, 11-15, 364-365n4-6. For “adaptive capacity,” see Merritt 2003, 52 and Kathleen Brown, “The Anglo-Algonquian Gender Frontier.” In Negotiators of Change: Historical Perspectives on Native American Women, ed. Nancy Shoemaker. New York: Routledge, 1995, 26–48. For rhetorical constructions of the Delaware as women, see Grumet 2009, 203-205; Merritt, 219-223; Fur, 160-198 passim. ↩︎

-

In the Wendell account book, women participated on 49.6% of all accounts and were sole account holders on 20% of accounts. In the Ulster account book, women participated on 51.6% of all accounts and were sole account holders on 22% of accounts. Waterman and Smith, 12, 19 and 47; Wendell, Waterman and Michelson, 17-18, 26-33, 196. For the intersection of land loss, debt, and political disenfranchisement for other Native groups, see Jean M. O’Brien, Dispossession by Degrees : Indian Land and Identity in Natick, Massachusetts, 1650-1790. Cambridge; New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 1997; Richard White, The Roots of Dependency : Subsistence, Environment, and Social Change among the Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983; David J. Silverman, “The Impact of Indentured Servitude on the Society and Culture of Southern New England Indians, 1680-1810.” The New England Quarterly. 74, no. 4 (2001): 622. ↩︎

-

Cole Harris, “How Did Colonialism Dispossess? Comments from an Edge of Empire.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 94, no. 1 (2004): 165–82; Mark Rifkin, Settler Common Sense: Queerness and Everyday Colonialism in the American Renaissance. Minneapolis: Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2014; Lorenzo Veracini, Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview. 2010. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010; Lorenzo Veracini, “‘Settler Colonialism’: Career of a Concept.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 41, no. 2 (June 1, 2013): 313–33. doi:10.1080/03086534.2013.768099; Patrick Wolfe, Settler Colonialism. New York: A&C Black, 1999. ↩︎

-

For examples of decline narratives in the literature of Iroquoia, see Robert Grumet, Historic Contact (Norman OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995), 346; Anthony Wallace, The Death and Rebirth of the Seneca (New York: Knopf, 1970), 23; Daniel K. Richter, The Ordeal of the Longhouse: The Peoples of the Iroquois League in the Era of European Colonization (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 260–261; Timothy J. Shannon, Indians and Colonists at the Crossroads of Empire: The Albany Congress of 1754 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2000), 26–27; Diane Rothenberg, “The Mother of the Nation: Seneca Resistance to Quaker Intervention,” in Women and Colonization: Anthropological Perspectives, ed. Mona Etienne and Eleanor Burke Leacock (New York: Praeger, 1980), 82. For critiques of this approach in the broader scholarship of Native North America, see Jennifer M Spear, “The Distant Past of North American Women’s History,” Journal of Women’s History 16, no. 4 (2004): 41–49; Gwenn A. Miller, “Contact and Conquest in Colonial North America,” in A Companion to American Women’s History, ed. Nancy A Hewitt (Oxford; Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2002), 35–48; Michelle LeMaster, Brothers Born of One Mother: British-Native American Relations in the Colonial Southeast (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012). On the recent scholarship on the eighteenth century development of Anglophone public vs. private spheres, see Mary Beth Norton, Separated by Their Sex: Women in Public and Private in the Colonial Atlantic World (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011); Terri L. Snyder, “Refiguring Women in Early American History,” The William and Mary Quarterly 69, no. 3 (2012): 421–50. On the difficulties of documenting Native women’s presence in masculine-coded diplomatic spaces, see MacLeitch; Fur, A Nation of Women, 4-5. ↩︎

-

On the potentials of big data for historians and other humanists, as well as general concerns in big-data projects, see Lev Manovich, “Trending: The Promises and Challenges of Big Social Data,” in Debates in the Digital Humanities, ed. Matthew K Gold (Minneapolis: Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2012), http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/15; Katharina Hering, “Digital Historiography and the Archives,” Journal of Digital Humanities, November 1, 2014, http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/3-2/digital-historiography-and-the-archives/; Jo Guldi and David Armitage, The History Manifesto (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 66–116 passim; Graham, Shawn, Ian Milligan, and Scott Weingart. Exploring Big Historical Data: The Historian’s Macroscope. Reprint edition. London: Imperial College Press, 2015 1-36 and 195-264. For a general overview of the practice of social network analysis by computer scientists and humanists, see Thomas Peace, “Six Degrees to Phillip Buckner? An Accessible Introduction to Network Analysis and Its Possibilities for Atlantic Canadian History.” Acadiensis 44, no. 1 (May 1, 2014). https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/Acadiensis/article/view/23130; David Easley and Jon Kleinberg, Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning about a Highly Connected World (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 16–17; Scott B. Weingart, “Demystifying Networks, Parts I & II,” Journal of Digital Humanities, March 15, 2012, http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/1-1/demystifying-networks-by-scott-weingart/; Stanley Wasserman and Katherine Faust, Social Network Analysis Methods and Applications (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994); “8000 Canadians.” Exploring Big Historical Data: The Historian’s Macroscope, February 12, 2015. http://www.themacroscope.org/2.0/8000-canadians/; “Dynamic Networks in Gephi.” Exploring Big Historical Data: The Historian’s Macroscope, September 19, 2015. http://www.themacroscope.org/2.0/dynamic-networks-in-gephi/. Network analysis maps relationships between many kinds of “stuff,” including things, places, ideas and people. See Weingart, “Demystifying Networks, Parts I & II.” ↩︎

-

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995); E Folsom, “Database as Genre: The Epic Transformation of Archives,” PMLA 122, no. 5 (2007): 1571–79; Adeline Koh and Roopika Risam, “Open Thread: The Digital Humanities as a Historical ‘Refuge’ from Race/Class/Gender/Sexuality/Disability?,” Postcolonial Digital Humanities, accessed July 1, 2015, http://dhpoco.org/blog/2013/05/10/open-thread-the-digital-humanities-as-a-historical-refuge-from-raceclassgendersexualitydisability/. ↩︎

-

On the practice of ethnohistory and “reading against the grain,” see Patricia Kay Galloway, Practicing Ethnohistory: Mining Archives, Hearing Testimony, Constructing Narrative (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006); Michael E. Harkin, “Ethnohistory’s Ethnohistory,” Social Science History 34, no. 02 (June 2010): 113–28; Amy den Ouden, “Locating the Cannibals: Conquest, North American Ethnohistory, and the Threat of Objectivity,” History and Anthropology 18, no. 2 (2007): 101–33. On the creation of archival silence as an active process of colonialism, imperialism, and slavery, see Stephen Best, “Neither Lost nor Found: Slavery and the Visual Archive,” Representations 113, no. 1 (2011): 150–63; Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe : A Journal of Criticism, no. 26 (2008): 1–14; Susan Scott Parrish, “Rummaging / In and Out of Holds,” Early American Literature 45, no. 2 (2010): 261–74. The phenomenon of colonial erasure or recasting of Indigenous histories is well known, but mainly examines the process of historical memory rather than erasure as an ongoing process from the moment of encounter. See for example Jill Lepore, The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity (New York: Knopf, 1998), 277–240; Joanne Rappaport, The Politics of Memory: Native Historical Interpretation in the Colombian Andes, (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 1998); Jean M. O’Brien, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence in New England, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010); Maureen Konkle, Writing Indian Nations Native Intellectuals and the Politics of Historiography, 1827-1863 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004); Susan A. Miller, “Native Historians Write Back: The Indigenous Paradigm in American Indian Historiography,” Wicazo Sa Review 24, no. 1 (2009): 25–45. For the erasure of women’s influence in familial networks, see Silvia Van Kirk, Many Tender Ties: Women in Fur Trade Society 1670-1870. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1983; Gary C. Anderson, Kinsmen of Another Kind: Dakota-White Relations in the Upper Mississippi Valley, 1650-1862. First edition. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1997; Jennifer S. H. Brown, Strangers in Blood: Fur Trade Company Families in Indian Country. Oklahoma paperbacks ed edition. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996; Susan Sleeper-Smith, Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounter in the Western Great Lakes. First Edition. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001. ↩︎

-

den Ouden, “Locating the Cannibals”; Lauren Klein, “The Image of Absence: Archival Silence, Data Visualization, and James Hemings,” American Literature 85, no. 4 (2013): 661–88; Alan Liu, “Where Is Cultural Criticism in the Digital Humanities?,” in Debates in the Digital Humanities, ed. Matthew K Gold (Minneapolis: Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2012), 490–506, http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/15. ↩︎

-

Wendell, Waterman, and Michelson, To Do Justice, 37, 55, 74, 101, 103. See the notes on individual entries in Wendell, Waterman, and Michelson; and Waterman and Smith for further discussion of how an individual’s gender was determined and determining if separate entries referred to the same individual. ↩︎

-

For a sociological overview of the whole-network concept, see Christopher McCarty, “Structure in Personal Networks.” Journal of Social Structure 3, no. 1 (2002). https://www.cmu.edu/joss/content/articles/volume3/McCarty.html. For a whole-network approach to a mixed Indigenous-French social network, see Robert Michael Morrissey, “Archives of Connection,” Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 48, no. 2 (2015): 67–79; Robert Michael, “Kaskaskia Social Network.” For discussion of the spatial extent of colonial influence in the lives of Indigenous people and multi-scalar approaches to the study of colonialism, see Silliman, Stephen W. Lost Laborers in Colonial California : Native Americans and the Archaeology of Rancho Petaluma. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2004; Voss, Barbara L. The Archaeology of Ethnogenesis : Race and Sexuality in Colonial San Francisco. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008; Jordan, Kurt. “Colonies, Colonialism and Cultural Entanglement: The Archeology of Postcolumbian Intercultural Relations.” In International Handbook of Historical Archeology, edited by Teresita Majewskiand and David Gaimster. New York: Springer, 2009. ↩︎

-

This value expresses the ratio of connections in the network to the number of all possible connections in a maximally dense network in which all individuals are connected to all other individuals. A value of 1 indicates the network is maximally dense; a higher density indicates that the network is closer to maximally dense. ↩︎

-

Network diameter indicates the shortest path between the two most distant individuals and an indicator of how many steps would be required to cross the network. ↩︎

-

The clustering coefficient is an indicator of a “small world” network. The higher the value, the more interconnected neighborhoods within the network are, while a lower value indicates that neighbors share fewer connections. ↩︎

-

Wendell, Waterman, and Michelson, To Do Justice, passim. See the annotations in Wendell, Waterman and Michelson for notes on likely identifications of some of these Native individuals in land deeds and other records. Very few of these other written sources documented specific connections to other Native individuals, and so were not incorporated in building this network. ↩︎

-

Wendell, Waterman and Michelson, [83] and [100]. ↩︎

-