The Old Bailey Proceedings, 1674-1913:

Text Mining for Evidence of Court Behavior

Citation for Original Article:

TH: This article took over five years to see the light of print, and was originally written in 2011, based on work undertaken in 2010. It reflects a particular moment in the evolution of the Digital Humanities, and of a wider project to visualise and analyse inherited text at scale. For me, it represents that moment when an online publication was changed from an 'edition' of an historical text, into a 'massive text object'that could be interrogated as a single thing.

WJT: The fact that this article was eventually published was due almost entirely to Tim’s tenacity. Journal reviewers at a number of venues argued that the readers of their journal simply weren't interested in these techniques and/or couldn't understand them. I have been teaching people how to program for almost 40 years: the process only works when everyone is open to growth and change. If not, I tend to go elsewhere.

TH: It is difficult to over-estimate the importance or novelty of 'counting' words in this context. This was not considered a normal form of historical analysis at the time and was instead a research strategy drawn from Corpus Linguistics and literary criticism. The adoption of word counting methodologies by historians marks one of the ways in which the more literary forms of the digital humanities (from Busa to Moretti) have changed the nature of 'digital history'.

The shortest trial report in the Old Bailey Proceedings is precisely eight words in length. In February, 1685:

Elizabeth Draper, Indicted for Felony, was found Guilty.

TH: The unusual character of the Proceedings as an online edition is a product of its own historical moment. The original project was designed in the late 1990s just after XML was proposed and defined, and at a time when OCR accuracy rates for even good quality text was low. It was also implemented during a period when 'rekeying' agencies established in the 1970s and 80s to assist companies in converting paper records into an electronic form, were seeking new clients as business records were increasingly 'born digital'. Both the accuracy of the underlying transcription and the nature of the tagging are reflections of specific historical conditions.

The longest trial is 320 pages, and more than 155,000 words long, and details the crime and conviction of William Palmer, found guilty of poisoning John Parsons Cook in 1856.1 Each of these trial reports, however, forms only a tiny fragment of the more than 27,000,000 words that make up the Old Bailey Proceedings 1674–1913 as a whole. Now available online, the Proceedings form the largest body of accurately transcribed histtorical text currently existing in an electronic form, and as a result provide a unique opportunity to explore an all-important historical source both as a single text, and as a collection of 197,745 generically related trial reports.2 Using computational methodologies based on “text mining,” this article serves three purposes.3 First, to provide a detailed description of the Proceedings as a single massive text object, illustrating how the distribution of text between sessions and between individual trials evolved between the late seventeenth and early twentieth centuries. Second, to com- pare these measures of a changing text to statistics reflecting the behavior of the court (patterns of prosecution and convictions), isolating how changes in the text reflect (or hide) changing patterns of court behavior. And third, to use these two measures in combination to both test the reliability of the Proceedings as evidence of court room practice at the Old Bailey in the eighteenth century, and of changing court behavior in the nineteenth. In the process it argues that “plea bargaining” was an early and commonplace component of nineteenth century justice; and that its history is best evidenced through the use of text mining methodologies.

TH: Digitising the nineteenth century Proceedings had been a step into the unknown; so work on the evolution of post-1834 material was inherently ground breaking; ensuring that the technical innovation involved was married to a new historiographical perspective.

The published reports of trials held at the Old Bailey, or Central Criminal Court in London between 1674 and 1913 have served for generations as an evidentiary touchstone for social historians and historians of crime and the criminal justice system. Since the publication of Dorothy George’s London Life in the Eighteenth Century in 1925, they have formed the first (and the frequently the last) point of inquiry into social relations, crime, and policing in eighteenth century London, although they have been largely ignored by historians of the nineteenth century metropolis,4 and in the work of a generation of legal scholars using a combination of “close reading” and statistical sampling, the Proceedings have provided the basis for a narrative of the development of the “adversarial trial,” the changing role of legal counsel, the rise of “plea bargaining” and summary justice, and the evolving functions of both judge and jury.5 The roles of legal counsel and the rise of defense counsel, in particular, have generated an extensive literature based largely in an analysis of the presence or absence of specific references to counsel in the trial reports contained in the Proceedings.6 This work has not entirely ignored either the changing nature, or the evidentiary difficulties presented by the Proceedings. Most historians would agree with John Langbein’s observation that their analysis is a “perilous undertaking, which we would gladly avoid if superior sources availed us.”7 Nevertheless, and through the work of Langbein, John Beattie, Simon Devereaux, Magnus Huber, and Robert Shoemaker, in particular, we possess a growing understanding of the changing nature of the Proceedings in the eighteenth century. We can chart many of the policy imperatives of the City of London, and their impact on what was published. We also have a more schematic understanding of the changing nature of the economics of production; and of the linguistic character of the text as a record of spoken language up to the first quarter of the nineteenth century. We know much less about the forces that shaped the Proceedings in the nineteenth century, but even for periods for which there exists a detailed literature, our understanding of the precise character of the Proceedings is fragmentary, and as they consist of 127,000,000 words, recording 239 years of legal administration and 197,745 individual trials, no one has actually read them in their entirety, nor ever will.

TH: The development of ‘massive text objects’ like the Old Bailey Proceedings, throws into ever sharper relief the extent to which historians have traditionally built their arguments on ‘texts’ without thoroughly interrogating the relationship between those inherited texts and a knowable historical reality. Part of the transition from a scholarly world characterised by information scarcity; to one marked by hyper-abundance is the need to re-think how inherited texts work. For me, this article represents a first step on that journey. See Ian Milligan, History in the Age of Abundance?: How the Web Is Transforming Historical Research (Montreal, CA: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019).

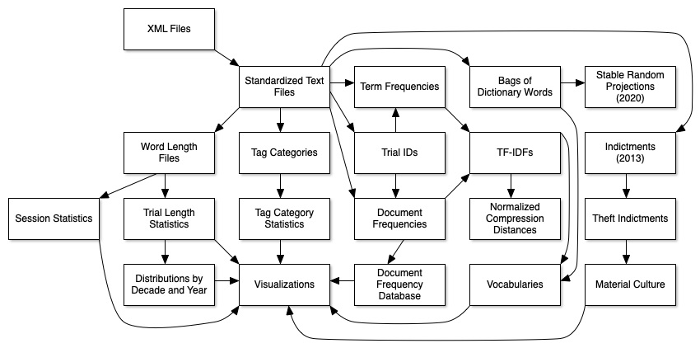

WJT: The code base that we used to explore the Old Bailey texts consisted of more than 60 Mathematica notebooks written over the span of a number of years. Along the way we created 1.78 million derivative files. These contain things like counts (4 animal thefts in 1674, 3 in 1675, etc.), bigrams (5 “cambrick handkerchief/handkerchiefs/handkerchieves” in 1740, 7 in 1741, etc.), and dictionary words (“alabaster” and “amethyst” and “archangel” all occurred in trials of 1845). Given the limits of our computing power at the time, we would typically read in a single trial, process it, and write the information to another file. Then we would summarize or visualize these derivative files. So our own analysis constituted a ‘massive text object’ of a different, but related, kind.

1. The Proceedings as a Massive Text Object

WJT:

One basic measure of the Proceedings as a text can be found in the numbers of words published each year. This reflects both the gradual evolution of the Proceedings from a few pages reporting brief trial summaries for a popular audience in the 1670s and 1680s, to their eventual role as a substantive record of what was said in court published as part of the administrative machinery of the criminal justice system for a narrow legal audience. Of course, the Proceedings were never complete.8 In the eighteenth century the shorthand recorder, Thomas Gurney, was happy to admit that he regularly excised repetitive witness statements; and in evidence given at the trial of Elizabeth Canning for perjury in 1754, reported: “It is not to be expected I should write every unintelligible word that is said by the evidence.”9 And from 1785 and then more consistently from 1787, evidence that was thought to present a moral danger to the reading public was excluded.10 In particular, from this date onwards, witness statements in cases of rape and sodomy were not reported. Between October 1792 and December 1793 all trials that resulted in a single verdict of “not guilty” were also censored for fear that defendants were gaining the upper hand in court, whereas for a short period in 1805, the City sought to exclude legal arguments made on behalf of defendants, worried they would publicize successful courtroom strategies.11 The kind of inconsistent and ambiguous relationship between the trials as reported in the Proceedings and the run of evidence given in court, even toward the end of their 239 year publishing run, is reflected in the three trials for malicious libel, conspiracy, and sodomy, respectively, involving Oscar Wilde and held over three sessions of the court in the Spring of 1895, which kept newspapers rapt for months, but are given precisely 22 lines in the Proceedings.12

Nevertheless, the number of words published in combination with the number of trials reported as having been heard each year (a more direct measure of the changing jurisdiction of the court and the rise of summary justice and police courts as alternative judicial venues) provides powerful evidence of the transformation of the Proceedings over time; and, more significantly, for historians seeking to use the Proceedings to evidence changing legal practice, illustrates that the changes in the length of the Proceedings can be attributed only in part, and only in certain periods, to the changing nature of court business.

TH: It is difficult to overstate how the ability to easily shift scales shaped this research. Because the nineteenth century Proceedings in particular were a largely unknown quantity, we were continually seeing patterns in the data that had no obvious relationship to the current historiography. The iterative discussion underpinning this article comprised a continual back and forth, of ‘look at this pattern’; ‘is it real?'; ‘what do you see when you drill down to the underlying trials?'; and ‘what does it mean?’.

WJT: Geoffrey Rockwell and Stéfan Sinclair, colleagues of ours on the Criminal Intent project, practiced a method of collaboratively investigating a text while developing the tools to do so. They were influenced by the agile software development technique of pair programming, where a pair of programmers share a workstation. Since Tim and I are based in Londons that are about 5800 km apart, we had to do this virtually. We kept in touch through regular email and video conferences. After 2019 the practice has become much more familiar. See Geoffrey Rockwell and Stéfan Sinclair,* Hermeneutica: Computer-Assisted Interpretation in the Humanities* (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016).

The existence of a digital edition provides an opportunity to analyze this source in new ways. Digital representations of texts have a number of characteristics that distinguish them from more traditional sources. The “transaction costs” involved in their use are radically reduced; however, more importantly, the types of information available for analysis are changed.13 In a limited sense, machines can “read” through vast amounts of digital text very quickly, even though they cannot fully understand it. This allows for machine reading to complement and supplement the work of “close reading” undertaken by humans as part of the task of exploring the character of large corpora of text and of locating shorter texts in their fullest context. This methodology builds on what Franco Moretti describes as “distant reading,” but more ambitiously enables the whole text to be examined in a form that facilitates the identification of large-scale patterns, while simultaneously allowing for detection of small-scale trends, and outliers. It creates a version of what Katy Börner has dubbed a “macroscope,” allowing large and small scale characteristics to be viewed simultaneously.14 The graphs presented with this article, therefore, are not solely designed to illustrate or highlight specific points, but rather to allow all the available data to be viewed at a single glance, and to facilitate an open-eyed engagement with the patterns revealed.15

TH: The ‘tagging’ applied to the Proceedings was originally designed between 2000 and 2001; and evolved into a complex overlay that sought to characterise crimes, verdicts and punishments; names and roles; and textual structures, from paragraph to trial to session. But it is important to remember that the tagging was originally designed around the parts of the Proceedings we understood best in 2000 (the materials published in the mid-eighteenth century), and was implemented at a time when general tagging strategies for historical material had not yet been fully defined. As a result, the tagging emerged as a consistent, bespoke ‘lens’ through which to view a rapidly changing textual object. We were generally able to revise the tagging to incorporate legal changes up to around 1830, but the volume and complex nature of later material largely defeated us. If we had built our tagging schema on a close reading of the last 50 years of the Proceedings, instead of the first, it would almost certainly have looked very different.

The electronic edition of the Proceedings has one additional characteristic that influences how it can be read. In constructing the underlying data set, texts were “tagged” to encode substantial information about each trial.16 For example, the trial of Elizabeth Draper, referred to earlier, has been tagged to indicate that “Elizabeth Draper” is a woman’s name, and that her trial was for a specific offense, resulted in a specific verdict, and took place at a given session. This tagging allows us to analyze predetermined types of data (verdict, for example), while simultaneously “mining” the text for characteristics (i.e., trial length) that have not been tagged.17

TH: The use of a ‘trial’ also has a substantial effect on the nature of the argument presented here. It creates the impression that a ‘trial’ in 1674, was somehow the same thing as one held in 1913. But the character of the criminal justice system changed dramatically through these 240 years. The rise of ‘plea bargaining’ (discussed and evidenced below), for example, measures the extent an Old Bailey trial became a rubber stamp affixed to a judicial process located elsewhere. The creation of a professional police, the increasing involvement of the legal profession, and the rise of the carceral state, all changed the nature of the ‘trial’. As a result, choosing trials as the unit of analysis both hides the dramatic shift in the administrative context for the Proceedings, and de-centres the experience of the defendant.

WJT: Text mining typically involves processes of standardization and simplification. In footnote 17 we discuss some of the technical details and decisions made when transforming the XML files into raw text. Other common strategies (which we also employed) include creating representations like ‘bags of words’, lists of all the words that appear in a text, along with frequency information for each. These might be further simplified by removing stopwords like ‘and’ and ‘the’, removing any words that do not appear in a dictionary or gazetteer, and so on. As far as I know, it is much less common to try to rethink the structure of the documents in the corpus. In our work so far, we have not made a serious effort to try to create a defendant-centric view of the Proceedings that gets away from the ‘trial’ as a unit of analysis.

The existence of a tagged version of the Proceedings as well as a full transcription allows for comparison of two consistent representations of the same text–one reflecting the tagged trials, and the second composed of the raw text of each trial adapted to facilitate “mining.” The process raises serious questions. Using “trial,” for example, as the basic unit of measurement for working with the Proceedings is problematic. Although the comprehensive online edition of the Proceedings contain 197,745 “trials,” it names more ethan 253,385 defendants, reflecting 211,112 offenses, committed against 203,501 victims. The use of “trial” as a unit of measure could hide variations in the numbers of defendants processed or offenses considered at each “trial;”18 however, the use of this unit of measure has the overwhelming advantage of reflecting the structure of the Proceedings themselves.

With this proviso, these gross measures of publishing and court activity confirm that the Proceedings both evolved significantly and did so in a complex relationship to the changing scale of court business, with the press of the number of trials contributing to the changing length of the published text to a different extent in different periods.

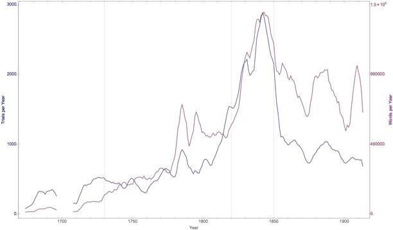

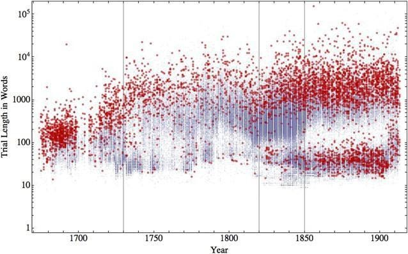

Figure 1.

Number of words published per year, 1674–1913 (dashed, scaled on the right), against the number of trials heard (solid, scaled on the left). Word counts are derived from trial text only and exclude prefatory material, advertisements, and punishment summaries. A 5 year moving average, or smoothing has been applied to both data series.

On the basis of Figure 1, the Proceedings can be roughly divided into two halves, at 1820 or thereabouts, with both the numbers of trials recorded and the amount of text published changing markedly. These two broad periods can in turn be roughly divided into four subperiods—1674–1730; 1730– 1820, 1820–50, and 1850–1913—each of which is characterized by a different pattern of both overall word length and number of trials recorded each year, and by a different relationship between these two measures.19

The first of these subperiods, 1674–1730, is marked by numerous gaps in either the publication history of the Proceedings, or in survival rates; and contains a large number of trials reported in only a few words.20 For these reasons, these early Proceedings have been largely ignored by historians of the criminal justice system as providing poor evidence of court behavior, and in this article will figure only in passing. Instead, the article will concentrate on the period from 1730 to 1820, and consider together the periods 1820–50 and 1850–1913.

The period from 1720 to 1820 reflects both the gradual transition in the nature of the Proceedings leading up to the 1730s, and a series of sharper movements in the length of the Proceedings in 1749, 1762, 1779, and 1793 that do not appear to reflect the number of trials heard in any obvious way. Similarly, the unusual character of the Proceedings in the 1780s, when the number of trials and words published appears to correspond is evident; as is the deterioration of the relationship between trial numbers and published words in the subsequent decades to 1820.

TH: The ability to precisely evidence changes in the characteristics of a serial publication over time is one of the great strengths of the methods deployed here. And while our analysis refines, rather than contradicts analyses generated by other historians; our approach has the subtle effect of focusing attention on the financial, structural and political context of the Proceedings, rather than their semantic content. To this extent, the methodology itself pre-determines the nature of the questions being asked.

WJT: If we were just starting this work now, we would be able to place much more emphasis on the semantic content of the Proceedings. Over the past decade, the rapid development of deep learning approaches to natural language processing (especially word representations) and the increase in computing power make it possible for individuals or small teams to take on much more sophisticated analyses.

Overall, the left hand side of Figure 1 reinforces Robert Shoemaker’s and Magnus Huber’s observation that the later 1720s and 1730s witnessed a marked transition in the nature of reporting found in the Proceedings. Both Shoemaker and Huber have suggested that these decades saw a gradual increase in the amount of text being published per trial, and, in Huber’s estimation, a more consistent attempt to represent the trial process in the form of individual, first person, witness statements. Beyond this, Shoemaker has argued that the period from 1729 to 1778 was characterized by a dynamic interplay between political and publishing imperatives that together shaped the Proceedings; encouraging increasingly extensive trial reports, while effectively censoring material that reflected the strategies of defendants, or that brought the system into disrepute. The apparently erratic relationship between the number of trials heard and words published would support his description of this period as one characterized by a complex interplay of forces, but adds to it a series of significant moments of transition.21 The evidence of Figure 1 also tentatively supports John Langbein’s observation that the period between September 1782 and December 1790—when Edmund Hodgson acted as the shorthand reporter—was a kind of “short golden age,” in which most trials were apparently reported at length, and during which the text of the Proceedings responded consistently to court behavior.22 And finally, Figure 1 is consistent with Simon Devereaux’s characterization of the last decades of the eighteenth century and first decade of the nineteenth, as a crisis of crime and punishment in which the Proceedings themselves served as an important tool wielded by City authorities in their ongoing attempt to promote the perception of “public justice.”23 The clear impact of changes in reporting practises between October 1792 and December 1793, when trials resulting in an acquittal were censored from the Proceedings as part of a wider strategy to sustain public confidence in the criminal justice system, reinforces Devereaux’s interpretation. Overall, and although confirming the broad outline found in the secondary literature for the period up to 1820, Figure 1 adds a new layer of detail, drawing attention to specific moments of significant change scattered across eight decades. The story of the nineteenth century Proceedings seems to fit less well.

TH: Langbein’s impression is almost certainly a result of the increasing significance of newspaper reporting of crime and trials. Most historians of the nineteenth century traditionally relied on publications such as The Times made easy to use as a result of the existence of Palmer’s Index. By contrast the nineteenth century Proceedings were never indexed, and only microfilmed in the late 1980s. In fairness to Langbein, the observation that the Proceedings ‘limped on’ could be referring to their declining readership, rather than their scope or scale.

The right hand side of Figure 1 reflects the trials and words recorded in the Proceedings in the period up to 1913, and appears to contradict John Langbein’s observation that following 1790 “the quality of reporting … declined sharply.. ..[and] the accounts of individual trials became more compressed,” and to belie his conclusion that they simply “limped on throughout the nineteenth century.”24

The sheer number of trials reported and words published in the nineteenth century is remarkable. In the short 30 years between 1820 and 1850, more than 33.5% of all trials covered by the Proceedings were recorded in 35,400,000 words (27.9% of all text), and although the number of trials heard per year declined from 1855 onwards, the amount of text dedicated to trial reporting remained consistently high in the second half of the nineteenth century (although marked by moments of rapid change in late 1870s and 1900s). More than two and a half times as many words (64,740,371/24,811,276), and almost three times as many trials (108,994/37,523) were recorded in the 70 years after 1800 than had been recorded in the seven decades before. More than this, Figure 1 illustrates the presence of significant transformations in the amount of text and number of trials heard from the 1820s, and in the number of trials recorded in the 1850s.25

This volume and changing character of this data calls into question the overwhelming tendency of legal historians to concentrate on the eighteenth century Proceedings at the expense of their nineteenth century equivalent, and evidences that a series of substantial changes in both the character of the Proceedings and the trials they reported that have not hitherto been subject to sustained analysis. Moreover, the close correspondence between the numbers of trials heard and the number of words published between 1820 and the mid-1850s, in particular, also demonstrates that this period represents one in which trials possessed a more consistent relationship with courtroom activity than had been true at any time in the previous century, with the possible exception of the 1780s.26 And finally, Figure 1 points to the existence of a hitherto largely unnoticed but dramatic transformation in either trial reporting, court business, or the relationship between the two, centered around 1855, which heralds a relatively consistent new form of either trial or reporting that continues through the early twentieth century. This transition correlates with the passage of “The Criminal Justice Act” of 1855, establishing new forms of summary jurisdiction. This basic text mining of the Proceedings adds a substantial layer of detail and granularity to the necessarily impressionistic readings that have been undertaken up until now, pointing to a series of specific moments that deserve further investigation; however, to test the nature of these moments of transition in the Proceedings we will move beyond looking at the total number of words published per year, to examining the text as a collection of 197,745 generically similar trial reports.27

2. The Proceedings as a Collection of Text Objects

TH: This approach helps to explain the difficulties we experienced in publishing this piece. A generic academic history article normally takes the form of a claim or argument, evidenced through a narrow selection of precisely relevant data. In contrast, this article purposefully presents a comprehensive set of data, on the basis of which the reader is guided to a specific conclusion. This ‘data first’ approach is shared with many articles in DH resulting perhaps from the ‘data enthusiasm’ of practitioners. But it also means that peer reviewers frequently read these articles as being overly descriptive.

Aggregate measures of words published per year hide substantial variations in the number of words dedicated to individual trials in a single year or session. Average trial length has been used by Shoemaker, Langbein, and Devereaux as evidence of the changing nature of the Proceedings in the eighteenth century, and by Shoemaker in particular to illustrate the role of the Proceedings in publicizing or suppressing particular types of trials rather than others. However, the notion of an “average” trial hides the distribution of trial lengths in any given session or year; a few long trials counterbalance many short ones, and expressing this relationship as an “average” effectively disguises the underlying distribution.28 In the year 1856, for example, the mean trial length was 1,124 words; however, more than 72% of trials were actually shorter than this, balanced by a small number of very long trial reports, including the 155,000 word account of the trial of William Palmer mentioned at the beginning of this article.29 Hitherto, historians have also necessarily been restricted to an analysis of a relatively small sample. The data presented here represent the first time a comprehensive measure of trial length for the complete set of 197,745 reports has been produced. It is purposely presented in such a way as to encompass all available data, rather than as a means of illustrating a particular pattern, and is designed to work as a “macroscope” in Katy Börner’s phrase.30 In other words, Figure 2, and subsequent scatter charts, were created as objects of study in their own right rather than as illustrations of patterns discovered by other means, and represent an explicit methodological intervention in how we study trial accounts.

WJT: The thing that struck me when I first plotted this figure was the upper and lower parallel bands between 1850 and 1900. What could explain the gap between them? Given the nature of the sources, we were observing a pattern that was the unintended consequence of tens of thousands of individual decisions; one which wouldn’t be observed for more than a century.

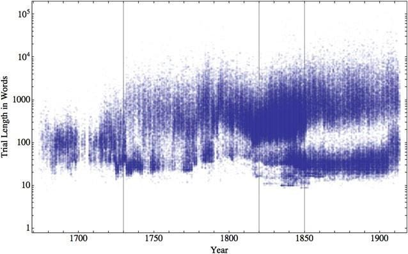

Figure 2.

A scatter chart of all 197,745 trials in the Proceedings measured by word length. Each dot in the scatter chart represents a single trial. Please note that the Y axis is a logarithmic scale.

TH: The use of a log scale is seldom commented upon (and did not exercise the peer reviewers). But it has the effect of emphasising patterns that would be largely obscured if the data was presented in a different format; and of emphasising the similarity between wildly disparate data objects. It re-enforces the ‘trial’ as an unchanging category, and subtly hides the variety of different judicial events reflected in a single session’s Proceedings.

WJT: Changing the scale of inquiry has often been historiographically productive, witnessed in the success of new approaches ranging from Microhistory to Big history. But, of course, microscopes and macroscopes can only ever show us parts of the whole.

The scatter chart of trial lengths by session illustrates that throughout the history of the Proceedings, but in distinct and different ways at different periods, some trials generated long reports, whereas others were recorded in a only a few words.31 The significant aspects of Figure 2 include the dense cluster of trials of a similar length between 1820 and the mid-1850s, and the clear space between trials clustering at the bottom of the distribution and those edging toward the top in almost all periods (the logarithmic scale tends to understate the distance between these essentially different forms of reporting). The dense accumulation of trials in the first half of the nineteenth century mirrors the steep increase in court business in these years evidenced in Figure 1, and reflects the extent to which most trials during these decades were reported in some detail. But the significance of the marked bimodality of trial length and its pattern of distribution is more difficult to identify. For eighteen decades, trials were recorded either with fewer than 100 words or thereabouts, or with substantially more, but almost never with approximately 100 words.

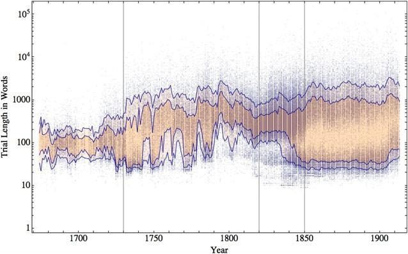

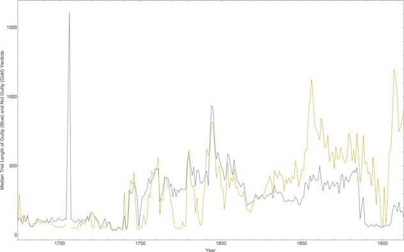

Figure 3.

A scatter chart of trials, with the 10th, 25th, 75th, and 90th percentiles marked as boundary lines. Please note that the Y axis is a logarithmic scale.

The precise nature of this bimodal pattern can be brought into sharper relief by looking specifically at the top and bottom quantiles in the overall distribution of trial lengths. Figure 3 reproduces the scatter chart of trial length by session, with the 10th, 25th, 75th, and 90th percentiles chosen as solid boundaries. Where the resulting lines are closest together, trial reports are most similar (at least as measured by word length); and where they diverge, the Proceedings are marked by a distribution that includes large numbers of distinctly different long and short trial reports.

Figure 3 reinforces many of the conclusions drawn from the wider distribution of annual word length identified from Figure 1, but adds to that analysis several complicating issues. In the first instance, it again suggests that the Proceedings can be roughly divided into two periods at approximately 1820, and four subperiods—1674–1730, 1730–1820, 1820–50, and 1850–1913—and that trial reports published prior to the mid-1720s were overwhelmingly short in length and narrowly distributed around approximately 100 words per trial. Significantly, Figure 3 demonstrates that this pattern then changes from close to May 1725 when George James took over the publication of the Proceedings. This is several years before the City of London’s December 1729 decision, highlighted by Robert Shoemaker, to expand the Proceedings with the explicit intent that “there will be more Room to enlarge upon Trials, they, being resolv’d (with all Regard to the Court) to have each Proceeding related in the fullest and clearest Manner, both with Respect to the Crime, the Evidence, and the Prisoner’s Defence.”32

However, more significantly, from the 1720s, the distribution of trials between short and long forms becomes much more variable for at least the next 70 years. The period from 1720 to 1810 illustrates rapid shifts in the distribution of trial length in 1724, 1732, 1742, 1749, 1761, 1768, 1779, 1782, and 1790, with periods of relative consistency marked out between.

The earlier dates, in particular prior to 1779, have not hitherto been identified as significant, although they clearly changed the nature of the trial accounts published. Two of these transitions, 1742 and 1768, coincide with changes in the publisher. July 1742 marks the first sessions paper produced by T. Cooper, and December 1768 represents the first produced by S. Bladon. The transitions in 1749 and 1761, on the other hand, map closely to the period following decision by the Lord Mayor, Sir William Calvert, to guarantee that the “Sessions-Book will be constantly sold for Four-pence, and no more, and that the whole Account of every Sessions shall be carefully compriz’d in One such Four-penny Book, without any farther Burthen on the Purchasers.”33 However, the apparently anomalous statistics for 1749–50, and the distinctive distribution of trial lengths for the next decade, suggests that as well as the printer, this pricing policy (in place through June of 1761), had a significant impact on the Proceedings as a text.34 The use of text mining in this analysis makes explicit and precise points of transition that would be difficult or impossible to identify using more traditional methodologies.

Later eighteenth century developments have been more thoroughly investigated. The City of London’s 1778 decision to demand that the Proceedings provide a “true, fair, and perfect narrative,” has been emphasized by both Devereaux and Shoemaker, and appears to have had a direct impact on their content from the following year. The significance of the short career of Edmund Hodgson as shorthand reporter (1782–90), highlighted by John Langbein, is also evident. The gradual nature of the changes in distribution at the beginning and end of Hodgson’s period in this role, however, implies that it was less transformative than Langbein suggests. Overall, Figure 3 confirms the distinct and rapidly changing character of the text as identified by Shoemaker, Devereaux, and Langbein for the period from the 1720s to the first decade of the nineteenth century, while, as with Figure 1, adding a new level of granularity and several additional points of transition to an already crowded list.35

More generally, these spasmodic transformations in the distribution of trial lengths in the eighteenth century reinforce Shoemaker and Devereaux’s conclusion that the Proceedings were responding to influences beyond the run of court business. Not only was text and the number of trials largely disconnected in these years (as seen in Figure 1), but the rapid changes in the distribution of trial lengths were also unlikely to have followed in the wake of changes in court practice, simply because of their rapidity. The kind of dramatic changes evident in 1742, 1749, 1761, 1768, 1779, 1782, and 1790 must be attributed to vagaries in reporting rather than to changes in the criminal justice system. In other words, and despite John Langbein’s identification of the period from 1783 to 1790 as a “short golden age,” supported as it was by the correlation between text length and the number of trials heard, evidenced in Figure 1, the whole of the eighteenth century publication should be seen as possessed of a problematic relationship with court room practice.36 This in turn makes their use as evidence for the rise of legal counsel and the adversarial trial difficult to sustain. It might be possible to separate out periods in the eighteenth century in which the distribution of trial texts are similar (i.e., 1730–42, 1749–55, 1770–79), but demonstrating that the nature of the reporting contained in the relevant trials is consistent and reflects a consistent relationship to court room practice would be much more difficult. At the same time, the more gradual pattern of change associated with the nineteenth century and the consistent pattern of reporting evident in the first half of the nineteenth century in particular, suggests that thisproblematic eighteenth century relationship between the Proceedings and the court changed with the century. Although many more trials were heard in the first half of the nineteenth century (as Figure 1 illustrated), trial reports remained typically longer than in the preceding century and were distributed more closely around a median. Figure 3 demonstrates that for the first 30 years of the nineteenth century at least, the vast majority of trials, approximately 90%, were reported at between 100 and 1,000 words, and that this represented the single period in the history of the Proceedings during which most trials were reported at a similar length. Figure 3 also illustrates that this pattern then gradually evolved to a mixture of longer and shorter trial reports between the early 1830s and 1850, with relatively few trials occupying the middle ground. Figure 1 highlighted the extent to which the number of trials and amount of text published at midcentury changed dramatically in 1855; however, Figure 3 suggests a more complex and gradual transformation occurring between the early 1830s and the mid-1850s. This new bimodal pattern of long and short trial reports then remains remarkably consistent and persistent through the rest of the century.

In some respects, the late nineteenth century pattern, the rise of a marked bimodal distribution, looks similar to that created by trial reports from periods such as 1730–42; however, whereas the pattern of trial reporting in the earlier period was short lived and inconsistent, reflecting changes in publishing policy, the long-term and consistent nature of the late nineteenth century pattern, and the gradual transition at midcentury, suggest a stronger relationship between the published trials and court business. Unlike the changes evidenced for the eighteenth century Proceedings, the major transitions in the nineteenth century reflect substantial and real transformations in the nature of trials held at the Old Bailey.

TH: The specific developments in London are worth noting here, as they were both early, and set the pattern for a global imperial system of justice. The establishment of the Metropolitan Police in 1829 ensured a ready pool of professional witnesses. And the rise of the penitentiary starting with Cold Bath Fields in 1792 gave judges (and juries) the ability to choose from a much wider variety of punishments to make the sentence fit the crime.

The nineteenth century criminal trial has been much less studied than its eighteenth century counterpart; however, in the work of Malcolm Feeley, based on a sampling of the Old Bailey trial reports—and more tangentially, Mark Haller, working from comparative United States statistics—at least one phenomenon that might account for the changes evidenced in Figures 2 and 3 has been identified. Feeley has argued that the nineteenth century witnessed the rise of “plea bargaining” as a standard component of the criminal process; essentially moving negotiation over punishment and guilt from the court and a jury trial to a pretrial process managed by legal professionals. The development of “plea bargaining” substantially explains the bimodal distribution of trial reports evidenced in Figure 3, as a “plea bargain” inevitably results in a plea of “guilty,” requiring no witness statements or legal arguments and generating very short trial reports. More contentiously, Feeley has also argued that this led to a “steady shift away from judge-dominated to lawyer-dominated proceedings”; and that this in turn removed many trials from the consideration of a jury, describing this transition as a result of changing professional legal practice.37

In contrast, and using a comparative approach to regional change in the United States, Mark Haller has located the same rise in “plea bargaining” as a legacy of a more complex set of structural transformations that effected the whole of the criminal justice process, citing the rise of professional police forces, the declining role of the victim of crime as a prosecutor, and the increasing use of imprisonment as a form of punishment, to explain why “plea bargaining” grew more commonplace across the whole of the Anglo-American legal world. 38

3. Testing the Attributes of Long and Short Trials

We will use data mining methodologies to further test the role of changing courtroom practice in determining the nature of the trial reports that made up the Proceedings in both the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (and the bimodal distribution evidenced in Figures 2 and 3), and the validity of Feeley and Haller’s emphasis on “plea bargaining” in shaping court room behavior in the nineteenth century by using tagged data to disaggregate the factors associated with trials reported at different lengths.

TH: The tagging schema applied to the Proceedings, includes ‘infanticide’, ‘murder’, ‘other’, ‘petty treason’ and ‘manslaughter’, under the broad heading of ‘killing’. But there are underlying legal and judicial changes that mean this broad category is not consistently used. ‘Manslaughter’, for example, evolved significantly over the period, and only becomes commonplace as a charge, after the 1810s. The degree of ‘seriousness’ reflected in these ‘killing’ trials, is itself subject to substantial historical change.

WJT: One approach that we have used in our work is to study the errors and outliers. In one example, we trained a machine learner to recognize instances of sexual assault. It ‘mistakenly’ classified trial t18360919-2166 as a sexual assault, even though human taggers had classified it as “Miscellaneous: other”. The entire trial reads: “2166. WILLIAM BLACKBURN was indicted for unlawfully and maliciously administering to Hannah Mary Turner 6 drachms of tincture of cantharides, with intent to excite, &c. GUILTY .—Aged 44.— Confined Two Years.”

One possibility is that the bimodal pattern evident in Figures 2 and 3 reflect the selective reporting of more serious trials in both the eighteenth century, and the latter half of the nineteenth, that forms of “killing,” for example, naturally took up a larger amount of both court time and space in the Proceedings than did petty theft.

Figure 4.

Distribution of trial lengths in words for “killing” displayed as black circles; all other trials are displayed as gray dots. “Killing” includes all trials tagged for the offenses of “infanticide,” “murder,” “petty treason,” “manslaughter,” and “killing: other,” by the Old Bailey online.

Figure 4 separates out “killing” from all other crimes, and in the first instance, evidences again a substantial distinction between the nature of the Proceedings in the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries.39 For the eighteenth century Proceedings, there is clear evidence that more words were devoted to “killing,” than to other types of crime, and that the bimodal pattern of reporting in this period was being at least partially determined by the nature of the offense. This eighteenth-century pattern reflects either longer trials for serious crime, or selective reporting of particularly shocking trials designed to engage a popular audience. In contrast, the nineteenth century pattern reflects just the opposite. The growing number of truncated trial reports at the bottom of the distribution from at least the 1820s for serious crimes, for “killing,” implies that the bimodal distribution of trial reports in the nineteenth century results from something other than either selective reporting or extended trials for serious offenses, and evidences a new role for “plea bargaining.”

Another way of testing and representing what appear to be two distinct and different regimes of trial reporting is to separate out and graph trials that result in a “guilty” or a “not guilty” verdict. This has the advantage of evidencing the issue of “plea bargaining” more directly, as trials in which this procedure feature inevitably result in a “guilty” verdict.

Figure 5.

Distribution of trial lengths in words for “guilty” (dashed) and “not guilty” (solid) verdicts. This data set excludes trials in which mixed and miscellaneous verdicts are recorded.

Similarly to other illustrations of these data, Figure 5 divides into two halves at approximately 1820, with each half possessed of distinct characteristics. In relation to verdict, the early Proceedings generally appear to report trials resulting in “guilty” verdicts in substantially more words than those used for “not guilty” trials. As was evident when examining the overall distribution in trial length during the eighteenth century, the distribution of trial length by verdict reflects a changing pattern marked by rapid shifts in 1724, 1732, 1742, 1749, 1768, 1779, 1782, and 1790, with short periods of consistent reporting between, but Figure 5 suggests a further layer of complexity, with selective reporting by verdict being applied very differently in what appear to be otherwise similar periods. Although, for example, 1768–79, and 1782–90 witness a similar overall distribution of trial length between long and short reports, the two periods saw substantially different levels of selection on the basis of verdict. The earlier period is marked by a pattern created through the very brief reporting of “not guilty” trials, whereas in the later period, the pattern is dominated by longer reports of “guilty” trials.

Figure 5 again provides strong evidence of the selective nature of the eighteenth century Proceedings, and contributes a further partial explanation of the bimodal distribution evident in trial length alone in this period. This supports Robert Shoemaker’s broad conclusion that eighteenth century trial reports were biased, with trials resulting in a “not guilty” verdict being substantially under-reported in most decades,40 but Figure 5 adds a proviso that this appears to have been substantially less true between, for example, 1742 and 1749, and 1755 and 1768, and substantially more true between 1768 and 1779, and 1782 and 1790. Figure 5 also modifies Simon Devereaux’s emphasis on the role of the Proceedings in promoting “public justice,” illustrating that it was the 1770s, rather than the 1780s or 1790s (as Devereaux suggests) that saw the most fervent attempts to privilege the reporting of trials resulting in a guilty verdict.41

In other words and as other measures of the eighteenth-century Proceedings have suggested, text mining for the distribution of verdict by the number of published words reflects the inconsistent and problematic relationship between trial reporting and courtroom behavior through the end of the eighteenth century. And as has been demonstrated through other measures, the nineteenth century Proceedings look rather different. From the mid-1820s, and then more dramatically from the 1840s, “not guilty” trials come to be reported at much greater length than those resulting in a “guilty” verdict. For the rest of the century, including the period on either side of the transition associated with 1855, when the number of trials heard at the Old Bailey declines sharply, trials resulting in a “not guilty” verdict dominate reporting; whereas trials with “guilty” verdicts are being reported in many fewer words. Simon Devereaux has argued that the Proceedings were increasingly relied upon to track judicial decisions from the 1780s onwards, and came to form an essential part of the pardon process from the end of the eighteenth century. This means that “guilty” trials that set in train a whole new administrative process needed to be more carefully recorded than did those resulting in a “not guilty” verdict. The brevity of trial reports for “guilty” verdicts therefore provides alternative evidence for Malcolm Feeley’s conclusion that “plea bargaining” came to substantially impact on the nature of the nineteenth century criminal trial.

To a very small degree, the truncation of these trials with “guilty” verdicts results from the exclusion of evidence heard at trials for rape and sodomy following 1787. And a handful reflect the changing role of medical evidence in scuppering a prosecution even after it had reached the court.42 However, rape and sodomy trials made up only 1.8% of all trials heard after 1800, and whereas the changing role of medical evidence was important in the 1820s and 1830s, it ceases to figure in the creation of short trials from this period onwards.43 Instead, this pattern of reporting in which trials with “guilty” verdicts were substantially shorter than those resulting in a “not guilty” verdict included large numbers of trials in which the defendant “pleaded guilty,” and were, by extension, subject to “plea bargaining.” In part, this evidence provides a substantial context to the detailed work of Randall McGowen and Deirdre Palk on the application of a “plea bargain” system by the Bank of England in its prosecution of forgers in the wake of the passage of the “Possession of Forged Banknotes Act” of 1801,44 but text mining for “plea bargaining” also demonstrates that what McGowen and Palk have described as a narrowly focused legal strategy designed to respond to the development of easily forged banknotes from 1797 formed a component of a much wider and more fundamental transformation in the practice of criminal prosecution.45 By the second quarter of the nineteenth century, and as Thomas Wontner observed in 1833, many defendants knew their “sentence before he went to the court.”46 On the basis of a sample of 1 year in 10, Malcolm Feeley has argued that the rise of “plea bargaining” began in 1835, and suggests that it grew to dominate court procedure by midcentury. Figure 5 evidences an earlier and more gradual beginning to the phenomenon of pleading guilty in part grounded in the strategies of the Bank of England, but also responding to systemic changes in the wider criminal justices system that encompassed new forms of prosecution practice in a wide range of cases.

We will further test the rise of the “guilty” plea and the role of “plea bargaining” by comparing these early nineteenth-century data to the behavior of the court as recorded as a series of tagged trial verdicts in isolation from the number of words used to report them, combining text mining with the statistical analysis of the legal process.

4. Testing Nineteenth Century Court Behavior

In addition to recording more or less of what was said in court, the Proceedings also record the legal niceties of each trial: the punishment, and as we have already seen, the charge and verdict. These measures have been “tagged” in XML and form a comprehensive, if schematic, record of every trial held at the Old Bailey from at least the early eighteenth century to 1913 (with the sole exception of the period between October 1792 and December 1793). The changing process of bringing a defendant to trial means that these data reflect courtroom behavior rather than crime or levels of prosecution.47 However, although only a tiny proportion of arrests resulted in a trial, these measures accurately reflect the experience of the defendants who were unlucky enough to find themselves standing at the bar of the Old Bailey. It has already been mentioned that the early nineteenth century witnessed a significant growth in the number of trials heard (see Fig. 1), and changes in both the number of defendants pleading guilty and the ratio between that number and all defendants found guilty can also be measured.

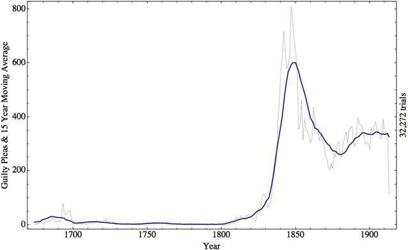

Pleading guilty was relatively common in the late seventeenth century and overwhelmingly resulted in a punishment of branding, which indicates that a form of plea bargaining was being practiced,48 but for most of the eighteenth century, Matthew Hale’s advice that defendants be encouraged to “plead [not guilty] and put himself upon his trial” seems to have held sway, and a guilty plea became a rare legal peculiarity.49 Figures 6 and 7 suggest that this changed significantly in the nineteenth century starting from as early as 1801.

Figures 6 and 7 illustrate that both as an absolute number and as a percentage of verdicts overall, guilty pleas began to rise from just after the turn of the century and grew steadily through the beginning of the 1830s, before rising dramatically over the course of the next two decades. Figure 7 suggests that this pattern then stabilized near 30% of all trials (and 40% of all trials resulting in a “guilty” verdict) before rising again from the 1880s to reach 40% of all trials by the turn of the century. Even among those accused of “killing,” 95 defendants pleaded guilty between 1825 and 1913, and their trials, therefore, appear among the shortest in the Proceedings. These guilty pleas imply a process of “plea bargaining” and support the broad outline of Malcolm Feeley’s analysis, as well as the importance of the role of the Bank of England from 1801 onwards.

Figure 6.

Guilty pleas, 1674–1913 (32,272 trials).

Figure 7.

Guilty pleas as a percentage of all verdicts, 1674–1913 (32,272/197.745 trials).

The precise explanation for the transformation evidenced in the rise of “plea bargaining” is beyond the scope of this article and requires detailed archival research into the process that led from arrest to trial. In this context, text mining and statistical analysis of the trial accounts alone can point to precise moments of transition, and broader patterns of change, but need to be paired with close reading and archival research in order to fully explain the forces in play. In particular, work needs to be done on the use of “guilty pleas” in cases of theft, on the correlation between “plea bargaining” and the growing use of imprisonment from the late eighteenth century, on the impact of the rise of a professional police culminating in the establishment of the Metropolitan Police in 1829 and the declining role of the victim as prosecutor from 1836, and, finally, on the declining role of capital punishment.50 However, the impact of the structural change evidenced by the rise of “plea bargaining” can be seen in one final measure drawn from the Proceedings: conviction rates.

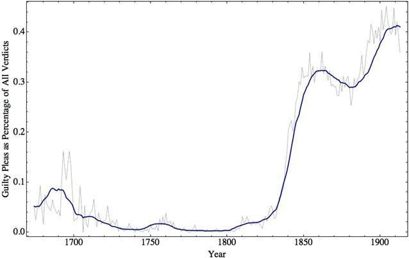

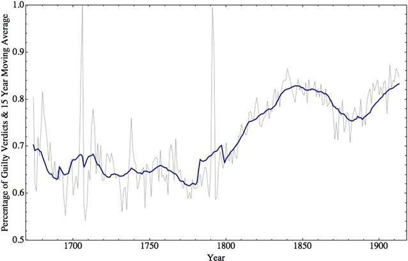

Figure 8 illustrates the substantial increase in the percentage of trials resulting in a guilty verdict, and correlates strongly with the rise of “plea bargaining.” From a relatively low conviction rate (in the region of 55–65%) during the eighteenth century, the first half of the nineteenth century sees a steady increase to between 70% and 80% in the 1840s and 1850s, before declining somewhat in the 1860s and 1870s (modern British convictions rates are just above 70%).

Overall, these statistical measures of courtroom behavior evidence a substantive change in the nature of the Old Bailey criminal trial over the course of the first half of the nineteenth century. The rise of the “plea bargain” fundamentally transformed the experience of the defendant, who by mid-century could almost guarantee that an appearance at the bar of the Old Bailey would result in only one verdict: guilty.

Figure 8.

Percentage of trials resulting in a “guilty” verdict. Between October 1792 and December 1793, trials resulting in an acquittal on all charges were excluded from the Proceedings. This exclusion has a marked and misleading impact on the moving average between 1777 and 1808; the apparently similar spike in convictions in 1706 results from a whole issue of the Proceedings being given over to a single trial, which was judged “guilty.” See s17061206.

5. Conclusions

Text mining in combination with the comprehensive statistical analysis of the Proceedings made possible by the creation of a digital edition, changes how these materials are read as evidence of courtroom procedure. For eighteenth century legal history, text mining for trial length suggests that in the eighteenth century the content of the Proceedings was significantly determined by factors beyond the run of court business, and that the relationship between what was published and what occurred at the Old Bailey changed from decade to decade and from year to year. This article suggests that before the Proceedings can be used to chart the evolution of court practice, or the rise of legal counsel, a much more granular and detailed understanding of the processes that created trial reports prior to 1800 needs to be incorporated. In contrast, for the nineteenth century history of the court, this article argues that the Proceedings represent a much more accurate reflection of courtroom practice and behavior than was the case in the preceding century. More than this, it argues that the rise of guilty pleas and “plea bargaining” and the growing conviction rates that mark the first half of the nineteenth century, and the dramatic fall in the number of trials heard at the Old Bailey in 1855, exposed through a combination of text mining and statistical analysis, reflects the dramatic evolution of court practice between 1800 and 1860.

Detailed archival work is needed to complement the “macroscopic” view provided by text mining. The professionalization of the police, the growing role of imprisonment, the changing role of the grand jury, and “lawyerization” (among a host of other influences) contributed to the changes identified here, but this methodology suggests that although historians of crime and the legal system have tended to place the major moments of transition in the evolution of the trial in the last quarter of the eighteenth-century and associated it with the rise of defense counsel and the adversarial trial, they have done so on the basis of a source that cannot be relied upon at this date. The methodologies deployed here suggest that when measured as both a text and a record of criminal administration, the Proceedings evidence a marked and substantial transition in the nature of the trial process as a whole clearly located in the first half of the nineteenth century.

TH: While this article has emphasised the positive side of ‘text mining’ as a methodology, it should also be noted that there remain many problems. Perhaps most obviously, the methods applied determine the nature of the questions that can be asked and answered. The use, for example, of ‘trial’ as the unit of analysis, arguably draws attention away from the experience of the defendant, or the nature of the crimes being prosecuted. Our methods also work to draw attention to the nature of the Proceedings as a publication, rather than as evidence of human experience. Subtly, the methods of digital history tend to make ‘text’ the object of study, rather than the human past.

WJT: I would reword Tim’s final sentence to this: “Subtly, the methods of history tend to make ‘text’ the object of study, rather than the human past.”

Text mining as a methodology helps test and problematize the assump- tions one brings to the evidence that is relied upon: to test both the quality of that evidence and the ways that it is used. In this instance, it allows for exploration of a text so voluminous that it could never be read in its entirety by a single person. It does not replace “close reading” and traditional archival research, but it does create a kind of macroscope, allowing the location of patterns made invisible by the sheer volume of inherited text. As the billions of words that make up newspapers, parliamentary reports, and novels become increasingly available in a digital form, text mining provides a new and different perspective. By analyzing these sources in light of the one characteristic they all share (their textuality) text mining allows one to combine a close reading of detail with the ability to focus on the broadest picture, to see patterns from a distance and to set new paths through the thickets of description.

In 1833, Thomas Wontner observed that defendants at the Old Bailey frequently lost their way in the speed and complexities of the trial process, such that, “on their return from their trials, [they] cannot tell of any thing which has passed in the court, not even very frequently whether they have been tried.” Text mining the Proceedings allows one to see the criminal trial in the round even when the crush of data is confusing, declaring with the defendants of the 1830s, “It can’t be me they mean; I have not been tried yet.”51

Tim Hitchcock is professor of digital history at the University of Sussex and co-director of the Sussex Humanities Lab <hitchcock.t@gmail.com>. William J. Turkel is professor of history at the University of Western Ontario <william.j.turkel@gmail.com>. This article derives from a “Digging into Data” research project, “Datamining with Criminal Intent,” jointly funded by the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC), National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). The authors thank all of the funders for their support, and their collaborators for their direct contribution to this work, including Dan Cohen, Frederick Gibbs, Geoffrey Rockwell, Jörg Sander, Robert Shoemaker, Stéfan Sinclair, Sean Takats, Cyril Briquet, Jamie McLaughlin, Milena Radzikowska, John Simpson, and Kirsten C. Uszkalo. The authors also thank the Old Bailey Online Team at the University of Sheffield and the Old Bailey Corpus Team at Giessen University; and in particular Sharon Howard, Magnus Huber and Magnus Nissel.

-

See Old Bailey Proceedings Online (hereafter Proceedings) February 1685, trial of Elizabeth Draper (t16850225-31); and May, 1856, trial of William Palmer (t18560514-490) www.oldbaileyonline.org,version 6.0 April 17, 2011. ↩︎

-

The uniquely accurate character of this transcription is the result of the project’s use of “double entry rekeying” to capture the original material up to 1834, and a combination of rekeying and optical character recognition (OCR) for the period 1834 to 1913. The resulting text is 99.99% accurate. This in turn, allowed a complex XML tagging schema to be applied to the transcribed text, reflecting offense, verdict, punishment, and other categories. In contrast, the vast majority of historical resources have used an unchecked OCR methodology, which when applied to historical materials results in a significant level of error, making the resulting digital resources more difficult to use in text mining, and largely impossible to tag accurately for structured information. The character and word accuracy rate across the whole of the British Library’s Nineteenth Century Newspaper Project, for example, is 78% for characters, and 68.4% for whole words, implying that almost one in three words is mistranscribed. See Simon Tanner, Trevor Muñoz, and Pich Hemy Ros, “Measuring Mass Text Digitization Quality and Usefulness: Lessons Learned from Assessing the OCR Accuracy of the British Library’s 19th Century Online Newspaper Archive,” D-Lib Magazine, 15 (2009). http://www.dlib.org/dlib/july09/munoz/07munoz.html Accessed July 28, 2016. ↩︎

-

“Text Mining is the discovery by computer of new, previously unknown information, by automatically extracting information from different written resources. A key element is the linking together of the extracted information together to form new facts or new hypotheses to be explored further by more conventional means of experimentation.” Marti Hearst, “What is Text Mining?”, School of Information Management and Systems, University of California, Berkeley, October 17, 2003 http://people.ischool.berkeley.edu/~hearst/text- mining.html ↩︎

-

M. Dorothy George, London Life in the Eighteenth Century, 2nd ed. (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1966). Since the Proceedings were published on microfilm in 1984, with an extended introductory pamphlet by Michael Harris, their role, particularly for the eighteenth century, has become more significant and they have served as the primarily evidential foundation for literatures on plebeian culture, crime and criminal justice, juvenile delinquency, popular and material culture, work patterns and industrialization, homosexuality, and the development of spoken language. See The Old Bailey Proceedings, Parts One and Two, 1714– 1834 (Brighton: Harvester Microform 1984); Central Criminal Court Sessions Papers, 1816–1913 (Dobbs Ferry, NY: Trans-World Microforms, 1981); and The Old Bailey Proceedings: A Listing and Guide to the Harvester Microfilm Collection, introduction by Michael Harris (Brighton, Sussex: Harvester Microform, 1984). For the recent use of the Proceedings as the basis for the history of crime see, for example, Anthony Babington, A House in Bow Street: Crime and the Magistracy, London, 1740–1881 (London: Macdonald, 1969); Douglas Hay, Albion’s Fatal Tree: Crime and Society in Eighteenth-Century England (London: Allen Lane, 1975); Heather Shore, Artful Dodgers: Youth and Crime in Early Nineteenth-Century London (Woodbridge: Royal Historical Society/Boydell Press, 1999); Frank McLynn, Crime and Punishment in Eighteenth-Century England (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 1991); Hal Gladfelder, Criminality and Narrative in Eighteenth-Century England: Beyond the Law (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001); and Andrew T. Harris, Policing the City: Crime and Legal Authority in London, 1780–1840 (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2004). For industrialization, male homosexuality, and linguistic change, see, for example, Hans-Joachim Voth, Time and Work in England 1750–1830 (Oxford: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press, 2000). Rictor Norton, Mother Clap’s Molly House: The Gay Subculture in England, 1700–1830 (London: GMP, 1992); Randolph Trumbach, Sex and the Gender Revolution, Volume One: Hetrosexuality and the Third Gender in Enlightenment London (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998); and Magnus Huber, “The Old Bailey Proceedings, 1674–1834. Evaluating and Annotating a Corpus of 18th-and 19th-Century Spoken English,” Annotating Variation and Change (Studies in Variation, Contacts and Change in English 1) 10 (2008), http://www.helsinki.fi/ varieng/journal/volumes/01/huber ↩︎

-

See, for example, John M. Beattie, Crime and the Courts in England 1660–1800 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986); John M. Beattie, Policing and Punishment in London, 1660–1750: Urban Crime and the Limits of Terror (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001); David Jeffrey Bentley, English Criminal Justice in the Nineteenth Century (London: The Hambledon Press, 1997); Peter King, Crime, Justice and Discretion in England, 1740–1820 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000); Norma Landau, ed., Law, Crime and English Society, 1660–1830(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002); John H. Langbein, “The Criminal Trial Before the Lawyers,” University of Chicago Law Review 45 (1978): 263–316; John H. Langbein, “Shaping the Eighteenth-Century Criminal Trial: A View from the Ryder Sources” University of Chicago Law Review 50 (1983): 1–36; Thomas A. Green, Verdict According to Conscience: Perspectives on the English Criminal Trial Jury, 1200–1800 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985); Douglas Hay, “The Class Composition of the Palladium of Liberty: Trial Jurors in the Eighteenth Century,” in Twelve Good Men and True: The Criminal Trial Jury in England, 1200–1800, ed. by James S. Cockburn and Thomas A. Green (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), 305–57; Martin J. Wiener, “Judges v. Jurors: Courtroom Tensions in Murder Trials and the Law of Criminal Responsibility in Nineteenth-Century England,” Law and History Review 17 (1999): 467–506; Malcolm Feeley, “Legal Complexity and the Transformation of the Criminal Process: The Origins of Plea Bargaining,” Israeli Law Review 31 (1997): 183– 222; David J. A. Cairns, Advocacy and the Making of the Adversarial Criminal Trial, 1800–1865 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998); Thomas P. Gallanis, “The Rise of Modern Evidence Law,” Iowa Law Review 84 (1999): 499–560; David Lemmings, Professors of the Law: Barristers and English Legal Culture in the Eighteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000); and Allyson May, The Bar and the Old Bailey, 1750–1850 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003). ↩︎

-

On the role of counsel in particular, see John M. Beattie, “Scales of Justice: Defense Counsel and the English Criminal Trial in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” Law and History Review 9 (1991): 221–67; S. Landsman, “The Rise of the Contentious Spirit: Adversary Procedure in Eighteenth-Century England,” Cornell Law Review 75 (1990): 498–609; John H. Langbein, The Origins of Adversary Criminal Trial (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), ch.3; Robert B. Shoemaker, “Representing the Adversary Criminal Trial: Lawyers in the Old Bailey Proceedings, 1770–1800,” in Crime, Courtrooms and the Public Sphere in Britain, 1700–1850, ed. D. Lemmings (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), 71–91; and. May, The Bar and the Old Bailey. This literature, although acknowledging the changing nature of the Proceedings as a text, has nevertheless largely relied on a straightforward count of textual references in relatively small samples of trials. See also Tim Hitchcock and Robert Shoemaker, London Lives: Poverty, Crime and the Making of a Modern City (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 180–91, 356–62. ↩︎

-

Langbein, Origins, 190––reiterating, without revision, his judgement on the Proceedings originally made in 1978. ↩︎

-

Most historians have accepted Langbein’s observation that “if the Sessions Paper report ‘says something happened, it did; if the report does not say it happened, it still may have.’” Langbein, Origins, 185, again quoting himself circa 1983. ↩︎

-

The Trial of Elizabeth Canning, Spinster, for Wilful and Corrupt Perjury; at Justice Hall in the Old-Bailey .. . 1754 (London: John Clarke, 1754), 19–20, 104. Quoted in Huber, section 3.2.2.2. ↩︎

-

See Proceedings, September 1785, t17850914-163. ↩︎

-

Simon Devereaux, “City and the Sessions Paper: “Public Justice” in London, 1770– 1800,” Journal of British Studies 35 (1996): 500. ↩︎

-

Proceedings, March 1895, John Sholto Douglas (t18950325_336); April 1895, Oscar Fingal O’Fahartie Wills Wilde and Alfred Taylor, (t18950422-397); May 1785, Oscar Fingal O’Flahartie Wills Wilde and Alfred Waterhouse Somerset Taylor, (t18950520-425). ↩︎

-

For digital history, see Daniel J. Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig, Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2005); and Daniel J. Cohen, Michael Frisch, Patrick Gallagher, Steven Mintz, Kirsten Sword, Amy Murrell Taylor, William G. Thomas III, and William J. Turkel, “Interchange: the Promise of Digital History,” Journal of American History 95 (2008): 442–51. ↩︎

-

Katy Börner, “Plug-and-Play Macroscopes.” Communications of the ACM 54 (2011): 60–69; and Franco Moretti, Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History (London: Verso, 2005). ↩︎

-

All programming for this project was done by Turkel in Mathematica 8 and 9 on Mac OS X. Mathematica is a proprietary development platform from Wolfram Research that is designed for technical computing. It integrates mathematical and scientific computing, visualization, data manipulation, and access to curated data, with the possibility of deploying documents that mix text and data with dynamic elements. See http://reference.wolfram. com/mathematica/guide/Mathematica.html. ↩︎

-

The “tagging” was done in XML, and the files for each trial incorporating the full XML markup are available on the Old Bailey online site. ↩︎

-

The “mining” of the Proceedings involved stripping out all XML markup, eliminating non-Latin and numeric characters, converting the text to lower case, and removing all punctuation. The resulting edition standardized the texts, facilitating counting words in a consistent manner. It should be noted, however, that there is a significant disagreement among linguists about what should count as a “word.” Is, for example, the formulation “John’s” one word, or two (i.e., name + possessive marker)? Larry Trask, “What is a Word?” (2004), Department of Linguistics and English Language, University of Sussex Working Paper LxWP11/04, https://www.sussex.ac.uk/webteam/gateway/file.php?name=essay what-is-a-word.pdf&site=1 Accessed July 28, 2016. ↩︎

-

The relationship between the number of “defendants” and “trials” for all complete decades (1720–1910) averages 1.32 defendants per trial. This ratio is slightly more variable prior to the early nineteenth century. For 1720–1810 this ratio ranges between a low of 1.18 defendants per trial in the 1800s, and 1.58 in the 1750s. The ratio of defendants to trialsfrom the 1810s onwards was more consistent, and ranged from 1.20 defendants per trial in the 1830s to 1.32 defendants per trial in the 1880s. The relationship between the number of “offenses” and the number of “trials” was more consistent in all periods, averaging 1.07 offenses per trial, and ranging from 1.02 offenses per trial in the 1810s, to 1.19 in the 1900s. ↩︎

-

These subperiods were initially identified using an unsupervised algorithmic “clustering” technique; however, the final selection of the boundaries was left to the judgement of a human observer, following multiple iterations of different clustering visualizations. ↩︎

-

The Proceedings have not survived or were not published for approximately one third of the sessions between 1674 and 1714. See Clive Emsley, Tim Hitchcock and Robert Shoemaker, “The Proceedings Publishing History of the Proceedings”, Old Bailey Proceedings Online (http://www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.0, 09 August 2016) ↩︎

-

Magnus Huber, “Old Bailey Proceedings, 1674–1834,” and Robert B. Shoemaker, “The Old Bailey Proceedings and the Representation of Crime and Criminal Justice in Eighteenth-Century London,” Journal of British Studies 47 (2008): 559–80. ↩︎

-

Langbein, Origins, 188. A measure of the relatively insecure and changeable nature of the role of shorthand reporter for the Proceedings can be found in Edmund Hodgson’s subsequent decline into abject poverty, and his eventual death in the workhouse belonging to St Andrews Holborn. See The Monthly Magazine, or, British Register Vol.XXXIV, Part II. For 1812: 506. ↩︎

-

Devereaux, “City and the Sessions Paper.” ↩︎

-

Langbein, Origins, 190, 189. ↩︎

-

For accounts of the changing volume and character of court business in the nineteenth century, see Clive Emsley, Crime and Society in England, 1750–1900, 4th ed. (Harlow: Longman, 2010), ch.8; David Philips, Crime and Authority in Victorian England: The Black Country 1835–1860 (London: Croom Helm, 1977); Clive Emsley and Robert D. Storch, “Prosecution and the Police in England since 1700,” Bulletin of the International Association for the History of Crime and Criminal Justice 18 (1993): 45–57. The best account of the changing volume of Old Bailey trials is David Bentley, English Criminal Justice in the Nineteenth Century (London: Hambledon Press, 1998), 55–56. ↩︎

-

This is not to imply that what was recorded in the Proceedings reflects accurately what was said in court, but merely that the relationship between the two remained the same from 1810 to 1855. The exclusion of sexually explicit evidence from trial reports from 1787 onwards is one measure of the distance between courtroom evidence and trial report (and helps explain historians’ relative uninterest in the nineteenth-century Proceedings). Simon Devereaux, “City and the Sessions Paper,” 481. ↩︎

-

The Criminal Justice Act, 18 & 19 Vic. c.126 (1855) established summary jurisdiction on a clearly defined basis, allowing people charged with minor theft and other offenses to be convicted by two justices. This act was amended only slightly by the Summary Jurisdiction Act, 42 and 43 Vic. c.49 (1879). Emsley, Crime and Society, 216. For a statistical approach to the impact of this legislation, see Chris Williams, “Counting Crimes or Counting People: Some Implications of Mid-Nineteenth Century British Police Returns” Crime, Histoire & Sociétés/Crime, History & Societies 4 (2000): 77–93. ↩︎

-

Shoemaker uses a sample of 271 trials drawn from the January sessions of 1720, 1730, 1740, 1750, 1760, and 1770, and Malcolm Feeley has created a larger sample of 3,500 trials (although Feeley charts a measure of “complexity” rather than trial length per se). Shoemaker, Robert B. (2008) The Old Bailey proceedings and the representation of crime and criminal justice in eighteenth-century London. Journal of British Studies, 47 (3). pp. 559–580. Malcolm M. Feeley, Legal Complexity and the Transformation of the Criminal Process: The Origins of Plea Bargaining, 31 Isr. L. Rev. 183 (1997). Both Simon Devereaux and John Langbein appeal to changing character and length of trial reports, but do so on a more impressionistic basis. Devereaux, “City and the Sessions Papers,” 468; and Langbein, Origins, 188. ↩︎

-

As the distributions of trial lengths are not normal, mean or average word length is misleading in almost all cases. For more information about the breakdown of the mean under departures from normality, see Rand R. Wilcox, Fundamentals of Modern Statistical Methods: Substantially Improving Power and Accuracy, 2nd ed. (New York: Springer, 2010). ↩︎

-