Parliament’s Debates about Infrastructure:

An Exercise in Using Dynamic Topic Models to Synthesize Historical Change

Citation for Original Article:

This article set out test whether dynamic topic models can enhance our understanding of the social, political, and cultural experience of technology in nineteenth-century Britain, using topic models at k=500 applied to Hansard’s parliamentary debates of Great Britain – that is, the text of the debates in the House of Commons and House of Lords, 1803 to 1911.

The article began as an exercise in bridging two fields – the history of technology and the digital humanities. I had already published a book about the history of technology in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain, Roads to Power (2010). I had also published my first experiments in the digital humanities, namely “Words for Walking” in the Journal of Modern History (2012), an article that applied a controlled vocabulary and word count to Google Books. We had mentioned topic modeling as an algorithm of possible use for historians in The History Manifesto (2014), but I had yet to systematically apply topic modeling to questions of history.

I was increasingly aware of the need for a systematic engagement with algorithms that answered basic questions about their ability to produce new historical knowledge. I decided, therefore, that the best possible proof would be to use topic modeling on the area I knew best – the history of state-built infrastructure in Great Britain – and to show what topic modeling could produce that confirmed the state of our knowledge, and where topic modeling allowed us to make new discoveries.

Can digital history enhance the toolkit of historians of technology? Some historians have prognosticated the application of text-mining tools to large-scale digital corpora such as the Google Books corpus, yet researchers have little to demonstrate what the application of ideas such as these would look like in practice. The history of the infrastructure state in Great Britain offers a good test case for whether text mining techniques can enhance historians' knowledge of a relatively long period.

One merit of the history of infrastructure is the rich historiographical context that a researcher works against in this field. The history of the state and technology is relatively well understood. Studies in the infrastructure state of Britain in particular are equally rich, with the Webb’s early study of bureaucratic innovation, The King’s Highway (1911), followed by research into the so-called “transport revolution” of Philip Bagwell and Derek Aldcroft, a nexus of technological innovation and labor management in canal, highway, and railroad that matched and undergirded other aspects of the industrial revolution.1 The timing of these improvements and their cause, whether state or market, have been the subject of renewed interest over the last decade, prompted by larger theories of infrastructure and the state formulated by Chandra Mukerji, James C. Scott, and Michael Mann.2 As a result, the British infrastructure state has become the subject of research by myself, Paul Slack, Dan Bogart, John Broich, and others. The British study of technology has been enhanced by quality studies of the Indian railroad, road, and canal system, while imperial histories of technology have long examined the relationship between empire and technological might in guns, steam, and surveying.3 Finally, not only infrastructure, but also the entire context of technologies, landscapes, institutional systems, and fossil fuel economies that constituted the industrial revolution have also been reexamined according to these questions.4 A broader critique of experts and expertise in imperial science and technology has problematized old triumphalist narratives of technology as the material equivalent of democracy, and explained sewers, embankments, abattoirs, and the pipes carrying drinking water as landscapes where state technology was deployed to manage the population.5 If text mining can illuminate this already well-plowed field, it surely merits our consideration.

A group of historians of technology gathered in Paris asked me to give a keynote after the History Manifesto, and I felt encouraged to speak about the confluence of the history of technology and digital history. I was then invited by a member of the same group to follow up at another invited talk at the University of Oklahoma, where Suzanne Moon of Technology and Culture encouraged me to write and develop this argument, and that openness made room for more of the essay to be spent on explaining the technology and the historical findings is produced. Around the same time, another group of historians of technology in Bogotá asked for a paper, and their ideas also contributed to the formation of this argument. The historians of technology were a wonderful and refreshing audience at a time when many digital humanists were having difficulty publishing quantitative arguments in mainstream journals. I credit Technology and Culture and the broader community of historians of technology for being already accustomed to understanding technology as a kind of cultural practice.

One of the pleasures of working with Technology and Culture was that readers familiar with the history of technology were already accustomed to thinking about a vast variety of technologies as cultural objects. It’s typical, in courses on the history of science and technology, for scholars to offer students a history of technology from steam power to the microchip, handling each innovation as simultaneously an innovation in materiality, culture, economics, and politics. Ironically, they were less interested in debating theories about what the technicality of digital methods implied – and more interested in examining what new methods could contribute by way of a historical argument.

This interest in argumentation over theory might reflect the fact that historians of technology already possessed a rich theory of technology as a cultural object that allowed them to transcend methodological wars raging elsewhere in the humanities. By reviewing the historiography above, I was nodding to a tradition that had long married culture and technology. What is not explicitly stated in this article is that the scholars familiar with the historiography cited above found it easier to take for granted the paragraph that follows – where I lay out the way that new kinds of information technology today make room for distant readings. In other subfields of history, the memory of the rebellion against the “quantitative turn” has assumed something like the status of a founding myth, such that historians who identify as cultural or social historians typically also identify themselves as scholars who necessarily reject quantitative history; the use of digital technology thus functions as a kind of “shibboleth” marking in-group and out-group. In Science or Technology Studies, by contrast, many historians who have embraced a cultural turn are also scholars who have paid minute attention to quantitative thinking in the past – consider the work of Bruno Latour of Chandra Mukerji. Because of this openness – as well as the subtlety of their thinking about technology as a cultural artifact -- I have found historians of technology in general to be a superb audience for digital methods.

This article will present a “distant reading” of the history of the infrastructure in the British Empire, demonstrating how topic modeling the parliamentary debates of Hansard can reveal new tensions and turning points that characterized the uptake of infrastructure over the longue durée. The application of text mining to Hansard reveals the importance of little-documented episodes that marked the progress of technologically-connected empire and its contestation, for instance the expensive and contested drainage and improvement of the River Shannon in the 1860s and the parliamentary contestation of the private telegraph connection between England and India around the same time. Text mining also helps us to identify a Whig or “Liberal” discourse of technology concerned with urban public spaces and hygienic publics, organized as early as the 1830s, against a Tory “Conservative” discourse of technology mostly concerned with military technology. Text mining can even illuminate the history of parliamentary spending on imperial prisons and parks, helping us to interpret the Fenian attacks on Phoenix Park and St. Stephen’s Green in Dublin. In short, digital techniques can help the researcher to generalize about the history of technology, its political context, and its cultural meaning, lending material for a historical synthesis that builds upon the insights of foregoing historians while potentially illuminating new directions for further research.

The topic model thus shows itself to be an invaluable tool to the historian of the infrastructure state: it reveals overlooked turning points in the history of technology and the state, structural differences in parliamentary positions visible over the longue durée, as well as informing our political interpretation of the cultural significance of particular parts of the built environment. This article will conclude by testing a digitally-informed synthesis of the history of imperial technology against existing historical consensus on the imperial history of technology. It ends by recommending a partnership between archival research and digital synthesis, demonstrating how the two methods can be used to enhance each other.

Topic Modeling

I had already begun experimenting with topic models several years before this essay was published. At the Harvard Society of Fellows, there were biologists who had used topic modeling to generalize about birdsong. When Cora Johnson-Roberson and I released the toolkit Paper Machines http://papermachines.org/, Cora had advised me that there was much enthusiasm for topic models as a way of synthesizing the major themes of research; she had designed Paper Machines with a tool for visualizing the rise and fall of discourses over time. Paper Machines' topic viewer depended upon static topics, unlike the dynamic topics used here. We had experimented with topic models, and I had given talks on the results, but at first, I was suspicious of the results. I came to dynamic topics later, working with data scientists at Brown University, who recommended to me the new papers. We proceeded with the Hansard debates by extracting topics at k = 10, 100, and 500, and by comparing static and dynamic topics, using different algorithms, and examining the results by hand. The first literature reviews that mentioned topic modeling (cited below) and the first studies applying topic modeling to historical questions were being published as we were doing our research.

The purpose of the section that follows was to give an account of what kind of work the algorithm of topic modeling did – and to investigate the kinds of generalization about the past that a topic model might help with – specifically, the identification of “discourses.”

Across the university system, scholars are teaching computers to make sense of large-scale textual corpora, to find turning points and to read context with more patience than a human being. Sociologist James Evans suggests that these methods of repeated pattern-matching are best understood by social scientists as promising to fulfill the mandates of social theory developed since the 1960s, for example, using text mining to identify patterns of repeated “discourse” as identified by Foucault, where historical structures of power and identity are visible in repeated patterns of speech and action.6

The method of textual analysis that we recommend is called “topic modeling.” Topic modeling has been effectively used to identify changing patterns of historical interest in academic journals, to critique the formation of a discourse of state power in Qing China, and to study the history of Bush-era engagement with terrorism.7 Discourse analysis studies using topic models been more frequently published in literary journals such as Poetics. History journals are only beginning to publish the preliminary results of topic modeling over time, even though Mats Fridlund and René Brauer advocated the application of topic modeling to historical questions some years ago.8

The point of this section was to be as pedagogical as possible, reaching an audience of historians without technical training, and making the case for the applicability of topic models to historical questions, which other humanists had made before me. Because this was a proof of concept article intended for an audience of historians of technology, my aim was to introduce topic modeling in a way that made sense to a lay audience. My literature review in footnotes 7-9 consists of a smattering of short articles introducing the concept of topic modeling and a possible “fit” between topics and humanities discourses. I also point to web-browser-based tools such as InPho Topic Explorer that put the tool within reach of historians with no technical background.

In the paragraphs that followed, I laid out basic parameters for the interpretation of topic models as they had been explained to me by my collaborators in data science, especially the “ranking” and the role of the first twenty words. I described basic rules-of-thumb for interpreting topic models as I had come to speak about them to my students, including a hypothetical description of how a computer might topic model an entire library. These descriptions were tailored so as to highlight some of the potential flexibility of topic models – for instance, the same word might appear in different topics – while underscoring practicalities identified by other digital humanists, for instance the way that topics seem to run in parallel to human discourses. I briefly reviewed some of the comparative work to date that had compared the effectiveness of different topic modeling strategies, then transitioned to the specific kind of topic modeling that this article relied upon – dynamic topic modeling.

In keeping with the principles of critical thinking that I later introduced as “critical search,” my intention in this section was to explain to the reader that the choice of algorithm was the subject of critical and evolving inspection and conversation, not automatic or routine prescription. The intention was to document my path to one particular algorithm – partially through emulation of other scholars' documented experiments, partially through critical inspection of alternatives – and to lay out, in a relatively concise way, the practical advantages that this path afforded. At the same time, I used lay language throughout.

Topic Modeling represents a subset of the branch of machine learning that is Natural Language Processing, whose other subcategories include machine translation and sentiment analysis. Topic modeling, like these other tools, deals in the computer-aided recognition of recurring structures. In particular, topic models deal in the probability that words co-occur together, and these probabilities are used to group together words that commonly are seen together. Various techniques of topic modeling have been developed since the early 2000s, and at present there are several software packages that can be readily deployed on a pre-existing base of digitized texts by a scholar with no computer knowledge whatsoever. Other scripts allow the scholar who has only the most passing acquaintance with command-line programming to topic model the data of her own choosing, although deploying these scripts on a text database the size of Hansard generally requires access to mainframe or cloud computing.9

The grouping of frequently collocated words tends to produce results that reflect broad generalizations about the invisible categories that structure mind, language, priorities, or prejudice in a given corpus.10 For instance, if we consider all of the books any given library, there is a high probability that the word “missile” is in the same book as the words “bomb”, “tank,” and “war;” there is a much smaller probability of “missile” co-occurring with the word “soufflé.” Topic modeling thus allows the scholar to generalize about discourses. It might be complemented by the same critical skills as the scholar close-reading a speech clamoring for war. Adding the close-reading skills that most scholars practice in seminar, the computer grants the power of recognizing patterns over hundreds of thousands of other texts.

The computer’s output takes the form of a list of the top twenty words in each grouping and a “ranking” that indicates how prevalent a particular topic is in the corpus overall Here is a topic model from Hansard about harbours:

| Topic number | Probability | Words in order of prominence |

|---|---|---|

| 181 | 0.00482 | harbor, pier, work, board, coast, harbors, construct, Dover, refuge works, refuge, improv piers, public, loan, grant, govern, place, money, trade |

Table 1: Coastal Infrastructure Topic

The first number is the “topic number,” which has been assigned by the computer as an identity. The second is a probability score, which tells us how often this topic occur, in this case, in approximately 0.4% of the time that Hansard is debating. Finally, the topic consists of a list of words, listed in decreasing order of likelihood of occurring. The words in this case have been “stemmed,” meaning that we have asked a computer to classify “improvement” and “improver” as the same word.11 The list of words here indicates that harbours, piers, and coasts are regularly spoken about, and that when parliament discusses harbours they also have to discuss where the funding will come from, and typically loans and grants may be involved. Finally, we come to the topic label. This topic has been named the “Coastal Infrastructure Topic,” and the label is scholar-assigned, and consists of the scholar’s interpretation of the data gathered by the computer.

As a result of this pattern-recognition, many of the results of topic modeling merely confirm general truths about discourse that the scholar already knows. In the case of the harbor topic, what we learn is that it was very likely, if piers and harbours were being discussed in parliament, that parliament was also talking about where the funding was coming from. If we apply topic modeling to all of Hansard, and we ask for a fine-grained level at 500 topics where each speech is understood as having its own discrete level, we get a fairly satisfying overview of parliament. The list of topics looks something like a table of contents of a textbook of nineteenth-century history. There are topics on abolition, paper money, the corn laws, the Napoleonic wars; workhouses, the great exhibition, the Sepoy Rebellion, Crimea, and so on. Within this basic overview emerge several topics that look like they pertain to infrastructure in particular: the creation and regulation of roads with tolls for carriages and later motorcars; the importance of the post; the improvement of rivers; and national conversations about railways (see Table 2). There are another twenty topics of this kind that do not appear on Table 2. They handle other familiar topics: the administration of telegraph and telephone by the postal service, the regulation of light in factories and the attempt to regulate smoke; the collectivization of municipal water and gas, and the improvement of piers and harbors. Everything looks familiar, and nothing is too challenging.

A protestation that became familiar to many digital humanists in the

2010s was the common refrain from question and answer sessions: “What

can Digital Humanities tell us that is new?” As I weighed my response

over the years, I came to realize that I was most excited about novelty

when text mining methods were applied to new corpora too large to read

through traditional means – for example, recent histories of

bureaucracies, or the voluminous output of online communities familiar

to readers now through Ian Milligan’s work. I had not begun modeling

Hansard because I believed text mining would produce a totally new

version of British history – that seemed unfathomable, given that

hundreds of British historians through the years had consulted Hansard

in detail. I was rather more curious about what kind of results would

come from comparisons of familiar turning points over long stretches of

time. As we pointed out in the History Manifesto, comparisons over the

longue durée have particular promise for digital analytics, because

humans cannot compare word count across decades with the rigor and

consistency of computers.

Along the way, some scientist – perhaps Simon DeDeo? – referenced this

rule, and I began to think about how relevant it was to our exercises of

text mining Hansard. Of course, we shouldn’t expect computers to give a

novel analysis in the first pass through a database that hundreds of

historians had read! If they did, that would probably mean that the

textual analysis was wrong. What were we looking for then? Surely, we

would want textual analysis, in the first instance, to validate common

subjects of consensus like the reality of the Transport Revolution, and

only in the second instance, to help us to see something new.

The importance of familiarity here is that it serves the purpose of validating a new method for scholars who are uncertain of how far computational algorithms can replicate scholarly processes. The lack of unfamiliar information should be taken as a sign of success, mimicking the “80/20” rule of thumb used by scientists that suggests that, in a good experiment, eighty percent of the results should look familiar, and no more than twenty percent of the results should be surprising. The fact that a topic model is capable of identifying regularly-occurring discourses in the past that are similar to the ones that a scholar of history might pick out given the same set of documents confirms that a topic modeling algorithm can carry out basic classifying work and report on the contents of documents in such a way that makes it useful for the scholar sorting large bodies of information without independently verifying each document on her own.

| Topic number | Probability | Words in order of prominence |

|---|---|---|

| Highway Regulation Topic | ||

| 39 | 0.00547 | road-, roads-, mile-, highway-, motor-, carriage-, toll-, turnpike-, speed-, traffic-, car-, horse-, repair-, cab-, main-, driver-, trust-, limit-, vehicle-, |

| Post Office Administration Topic | ||

| 164 | 0.00467 | mail-, service-, post-, general-, service-, postmast-, postal-, letter-, mails-, train-, contract-, arrange-, convey-, London-, company-, office-, packet-, railway-, delivery-, arrive-, |

| River Infrastructure Topic | ||

| 190 | 0.00466 | river-, drainage-, water-, work-, drainage-, board-, navig-, sewag-, shannon-, thame-, conserve-, navigation-, thames-, canal-, works-, flood-, carri-, land-, district-, improv- |

| Railway Topic | ||

| 4 | 0.00936 | railway-, line-, company-, railways-, construct-, great-, light-, western-, interest-, company-, public-, mile-, scheme-, traffic-, guarante-, work-, railroad-, companies-, promot-, propos-, |

Table 2: Selected Infrastructure Topics from a 500-Topic Model of Hansard, 1800-1910

Even while topic modeling correctly identifies several well-known features of the history of British infrastructure, the method also offers the capability of turning up occasional unknown turning points that were debated within their own time. The most surprising result is the appearance of the word “Shannon” in a discussion of river improvement and drainage, occurring even earlier than the more familiar Thames in the same topic, a little-documented feature of imperial infrastructure history. The computer’s ability to retrieve this event is significant, as it sheds light on microhistorical studies that have not been adequately positioned in terms of their historiographical context. The implications of this finding will be discussed at greater length below.

An important enhancement of topic modeling for historians is “dynamic topic modeling*,*” one category of tools for discerning how language changes over time.12 The earliest dynamic topic models were created in 2006 by computer scientist David Blei to understand how a particular topic changes over time.13 In essence, the computer is instructed to find a basic topic, and then it is further given a budget for ways that the basic topic might change from decade to decade. Dynamic topic modeling has been applied to the distant reading of journals in computer science and engineering with good results.14 It has even been applied to the debates of the European parliament, where political scientists have used a type of dynamic topic model called NMF (non Negative Matrix Function) that uses matrices rather than probability to find change over time, with the result of picking up nuances better.15

I was urgently aware, as I was writing this, about concerns from humanists about the reliability of digital methods, and of topic modeling in particular. I wanted to guard against charges that topic modeling was a “black box,” and therefore an unknowable technology whose results merited distrust. I had asked my collaborators -- data scientists at Brown University – to direct me to literature about every technical variation on topic modeling available. We had run results for both LDA and NMF topics, and the results that I chose to examine in detail were those that seemed, both in the literature and in practice, to produce more reliable results for change over time. This iterative practice of engaging an algorithm by examining its variations and their results in detail became the seed of the epistemological approach to digital methodologies that I later outlined in the article “Critical Search” in The Journal of Cultural Analytics.

| Rank w/i Topic | Overall Topic Keywords | 1810 | 1810 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 | 1860 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | post- | office- | palmer- | post- | post- | office- | office- | telegraph- |

| 2 | telegraph- | post- | pitt- | postmaster- | office- | post- | post- | post- |

| 3 | postmast- | build- | eden- | depart- | hill- | fill- | patent- | crawford- |

| 4 | mail- | accept- | post- | postag- | letters- | accept- | record- | messag- |

| 5 | stamp- | situation- | patent- | mail- | postag- | held- | postmast- | electr- |

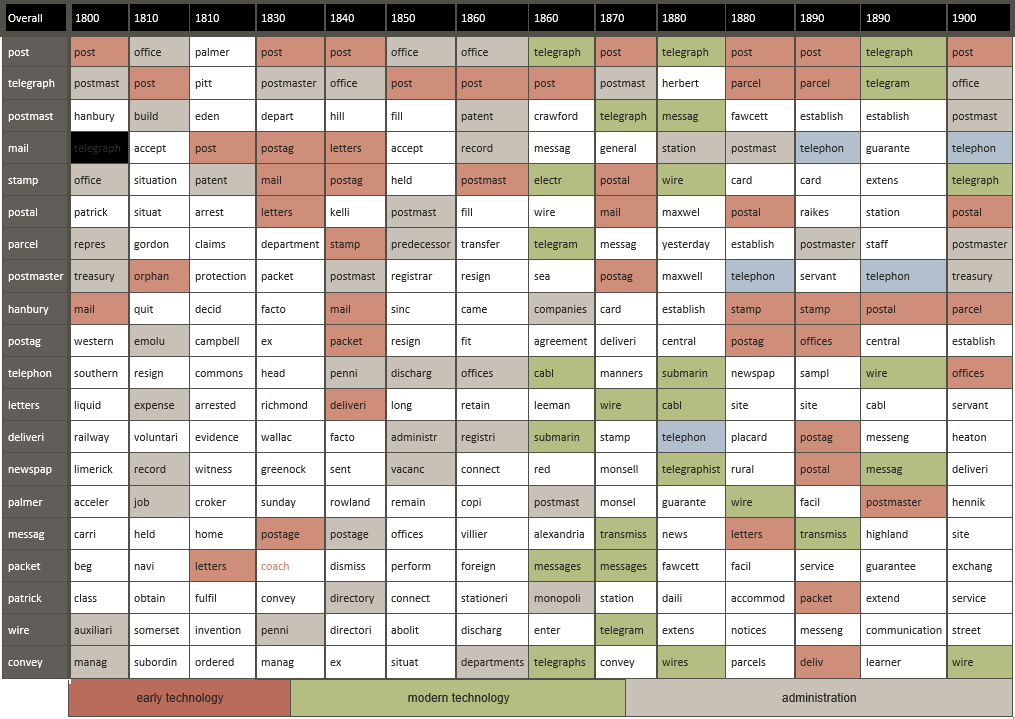

Table 3: Excerpt of “Post Office Topic” 1810-1870 from Dynamic Topic Model of Hansard

I was extremely wary of the question of to what degree topic models produced interpretable results that could be used by historians. I was still skeptical, but I decided to make my skepticism of topics part of my pedagogic practice. I began to take a stack of printed dynamic topics, like the one above, on tour with me as I gave talks. I would hand out a stack of topics based on Hansard to the audience – even when the audience contained no historians of Britain. After a talk on innovation in digital practice, I would explain the theory of topic models, as well as my doubts, and I would ask the question: do you think the words in question give an accurate or interesting portrait of change over time? I would ask audience members to physically mark up the topic with pen and highlighter, circling nouns or underlining verbs, and working with a partner until they had something to talk about. On several occasions (but especially in one particularly vivid meeting at the Université de los Andes in Bogotá, where I was speaking at the invitation of Alexis de Greiff and Stefania Gallini), I was astonished by the extent to which audience members were willing to fight for the topic as a tool for doing research. Carefully poring over one topic at a time tended to produce precise insights about names and places that intersected with an overall portrait of the time. I would say that it was therefore the audiences in these meetings – rather than the data scientists – who taught me how to read a topic model, and this article is very much a reflection of the insights that happened in those meetings.

The output of dynamic topic modeling is a chart like the one shown in Table 3, where the first column from the left shows the rank of prevalence of each word in that decade, and the second column from the left (highlighted in dark gray) represents the basic topic (the equivalent of the normal LDA topics we saw in the previous slide). Each column to the right represents a new decade as we move from left to right. Table 3 demonstrates that the computer picks up the introduction of new technologies such as the postage stamp and the telegraph, accurately identifying the 1840s and the 1860s as moments of technological adaptation, as well as known moments of bureaucratic reorganization like the debate over the remuneration for the patent on the post coach system awarded to Palmer in 1785, still under debate in 1810. As with the static topic model discussed above, the results are mostly validating of the method and do not present new evidence. The only surprise is the name of Crawford, a reference to a little-studied Royal Commission on ownership of the telegraph between England and India. The significance of this finding will be discussed further below.

In this article, I was careful here not to overstate my budding faith in topic models. Each sentence in the above paragraph matches an observation that matches details in the topic models to historical facts debated in parliament. I chose the topic of infrastructure, in part, because the infrastructure topics offered the few computational accounts where I already knew how to interpret the majority of the names and debates referenced. I could therefore accurately judge what was new to the historiographical literature that could be learned from a topic model.

The issue of background knowledge raises important pedagogical questions. If a PhD in the history of British infrastructure is a prerequisite for accurately interpreting a topic model, what use would undergraduate history students have for topic modeling? How could they possibly learn from a topic model, or correctly identify what was historiographically interesting in its returns? In the classroom, I typically encourage students to recognize that the tools of digital analysis are a supplement to an older humanistic traditions of careful reading, comparison, and historical analysis, not a replacement thereof. My assignments interweave digital tools such as topic modeling, word vectors, etc., with trips to the library in search of secondary sources and lessons that concentrate on the close reading of the texts. These are difficult lessons, particularly for non-history majors, who are accustomed to thinking of code as a form of analysis that is entirely self-contained.

In the remainder of this article, we will turn to larger topic models are laid out in spreadsheets that can be quite challenging to read. In this case, the scholar is reading the dynamic topics from an all-Hansard model for words about technology, infrastructure, and the built environment, hoping to find patterns that replicate, enhance, or nuance the guns-maps-and-steel thesis of earlier scholars. We will not, in the main, be following up on the keywords in context, leaving those investigations for a later scholar. The point of this exercise is to see how far the topic models by themselves can take us, thus allowing us to test the hypothesis that topic modeling provides a methodological innovation supporting longue durée and comparative analysis in the history of technology.

For instance, let us return to the case of the topic about the post office. Looking at a full spreadsheet of the entire period from 1800 to 1900, and drawing out words related to technology, infrastructure, and the built environment allows us to tell a fuller story. The information still contributes little that is new: a technological regime of coaches and letter delivery in the early nineteenth century gives way to a technological regime based around telegraph wires and telegraph stations later in the century.

Table 4:

Post Office Topic, Dynamic Topic Model of all Hansard Debates, 1800-1910[^16]

The layout of this table is an attempt to more-or-less capture the dialogue about topics that happened in Bogotá, where historians – mainly from Latin America – helped me to mark up a series of dynamic topics from the nineteenth-century Hansard. By circling or underlining certain word-forms or themes, the long list of words became more readable by humans trying to understand change over time. In the table, I have rendered the patterns I found in through the use of color; using gray, red, and green to mark up different subjects results in a visualization of a temporal discontinuity around 1860. What is interesting about this is that the output of the dynamic topic model does not, in itself, make the temporal discontinuity explicit; it is scholarly attention applied on top of the dynamic topic model – closely reading the topic model as one might closely read a document, if you will – that allows the scholar to notice a discontinuity.

The dynamic topic model offers more information, however, if we use color to illuminate the technological shift. In red, keywords are highlighted that pertain to stamps, letters, post offices, and delivery, a discourse that persists from early in the century until late; it doesn’t go away, as we might have assumed at a first glance. In green, keywords are highlighted that reference the new technology of wires, telegrams, and telephones that becomes a large part of parliament’s concern with the Post Office after 1860.

This line of argument about a bureaucracy being set into motion that then sustains later revolutions in the history of technology came directly from my reading of the dynamic topic model; it makes sense from my reading of nineteenth-century bureaucracy that this dynamic exists, in which – to use a metaphor from Reinhard Koselleck – geological layers are laid down in one era, and then new innovations are laid on top of them. But that generalization would not have occurred to me had I not been poring over the dynamic topic model, trying to make sense of the dynamics of continuity and discontinuity in the words in front of me. Nor did that explanation of geological layering come all at once; it was only after the dynamic topic model had been marked up, and the red and green explained, that I found myself asking how it was true that parliament was no longer talking about postmasters in 1880 as they had been in 1820. In such a way, “zooming out” from the past with the help of macroscopes allows the scholar to reduce the dynamics of time into a single view, such that vast dynamics, unfolding over decades can be articulated with the precision of a literary scholar performing a close reading on a poem.

Even more illuminating is the section highlighted in beige here: a discourse about administration, that includes the employment or discharge of postmasters and other officials, the recording of their work, and the subdivision of post offices into departments. This topic also handles the granting of patents, monopolies, or emoluments to the originators of the reformed post-coach system of 1785 and the new penny-postal system of 1840, and the expense of maintaining the system of a national post office with inquiries from the Treasury running throughout the period. What the gray topic reveals is that the bureaucracy set up before 1860 was able to adapt to new technology in the following decades.

I would have hesitated to stand behind so bold an assertion about the ability of topic models to produce new insight into the longue durée had I not been working with a topic model about the post office, having just completed a study of roads, post, travelers, and bureaucracy from 1746 to 1848. I could confidently assert that the topic model showed me something new about the shape of bureaucracy over that time period, at which I had not been able to arrive on my own through primary and secondary readings.

The century-long dynamic topic model of the Post Office pushes past the initial insights of the smaller model to reveal some of the institutional patterns of bureaucracy and technology that typified the experience of a century. Distantly reading the Post Office through Hansard allows the reader to glimpse some particular structures of the debate: a shift from early technology to modern technology, and the significance of earlier debates about employment and regulation that set up the Post Office and were not significantly revisited in later years.

We see from this example that the distant reading of topics in parliamentary debates can unveil shifting concerns and attention to different administrative structures. It can mark out watershed moments, for instance the attention given to a new technology. We can apply this same technique of examining topics in other domains, for example divisions of institutional and party outlook, the infrastructures of empire, and the relationality of different landscapes and technologies that occur within the same debate.

Institutional Divides

The line of investigation of dynamic topic models changes here from the historical material with which I was most comfortable – the history of postal bureaucracy – to the question of other forms of technology. My reading of the literature was that recent generations in the history of technology had little touched the army and navy – at least since Neil Headrick’s account of the use of technology in building empire. It seemed improbable that we would learn anything about the politics of imperial technologies beyond their use in subordinating Britain’s colonies. The Army and Navy therefore seemed like perfect material upon which to ask a naïve question: might we be able to discern new historical discontinuities in the nineteenth century, if we worked with a dynamic topic model, and could digital methods therefore tell us anything new?

We can test how far such a topic is useful in comparisons by examining two topics about similar institutions and their approaches to infrastructure. How, we might ask, do two different institutions compare in their approach to infrastructure, for instance the army and navy, or the Conservative and Liberal parties?

| 1810 | 1820 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| railway- | project- | telegraph- | ships- | iron- | traffic- | construct- | |||

| railroad- | traffic- | ships- | cable- | fleet- | engine- | traffic- | |||

| road- | road- | dockyard- | trunk- | trunk- | |||||

| canal- | map- | lines- | lines- | ||||||

| railroad- | telegraph- |

Table 5: Mentions of Infrastructure in the Army Topic

If we pull up the topic related to the army, we find a consistent interest in technology across the period, one that shifts from road, canal, and rail to maps, telegraphs, ships, shipbuilding, and trunk lines towards the end of the century. There are more technological terms discussed in 1840 and 1900 than in the other decades, when technological terminology is not part of the top twenty keywords debated by parliament.

| 1810 | 1820 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sea- | dock- | dock- | dockyard- | dockyard- | construct- | iron- | dockyard- | dockyard- | dockyard- |

| station- | coast- | ships- | dockyards- | fleet- | dock- | dock- | battleship- | ||

| dock- | station- | fleet- | dockyard- | shipbuild- | station- | coastguard- | |||

| build- | gunboat- | gun- | contstruct- | ||||||

| packet- | coastguard- | channel- | |||||||

| ordinance | gibraltar- | ||||||||

| stores- | station- |

Table 6: Mentions of Infrastructure in the Navy Topic

As I explain here, the payoff of the question asked above is knowledge of historical discontinuities in 1840 and 1900. Essentially what is happening is that the use of topic models helps the historian to identify new historical turning points – a moment of enthusiasm for technology twice in the nineteenth century – in a chronology that is markedly different from that in the literature, which leads us to expect the Great Exhibition of 1851 as a turning point. Topic modeling thus points us to hidden dynamics of the life of technology in the past for which I still have no explanation – why would there have been a sudden moment of enthusiasm for technology in 1840 and 1900? In this way, using topic modeling acts much as critical theory does, in that it opens up the field of the past to new questions: in this case, questions of pure temporal discontinuity.

We can compare the Army topic to a topic related to the Navy and its expenditures. The navy, unlike the army, is interested in dockyards and battleships. Importantly, the same temporal structure prevails in both cases: 1840 and 1900 jump out as two moments when forms of technology predominate over other concerns in the parliamentary debates. The structure of technology within the topics shows that parliament was willing to entertain the importance of technological adoption for the army and navy not based on the temporality of engagement, for instance during the Sepoy Rebellion, Crimea, or Suez. Rather, serious engagement with new technology happened at moments of dynamic technological innovation, when the attention of parliament was shifted by the newborn railroad and around 1900 with the telegraph – but this shift occurred forty years after the telegraph had been adopted to use by the post office.

We might hypothesize that the explosion of debates in 1840 and 1900 reflect technological enthusiasm in parliament, driven by revolutions elsewhere much vaunted in the press: for instance, the earliest reports of the railway and those of the internal combustion engine, both of which events seem to have propelled parliament into advocating for already-existing technologies such as road, map, dockyard, packet, and ship channel as well as the new technology of railroad, telegraph, and battleship. For the army, a world of road, rail, and map making shifts to telegraphs and trunk lines, and the navy has undergone a shift of technology from packets to battleships. Technological enthusiasm in parliament seems propelled to entertain army and navy applications around new technology only at particular moments of innovation.

Clearly we would need more information to interpret this particular example. Nevertheless, shifts of interest across topics point us towards institutional shifts at moments of shared activation: 1840 and 1900 as moments when parliamentary will solidified to drive Britain’s military technology forward.

| 1850 | 1860 | 1860 | 1880 |

|---|---|---|---|

| hall- | morton- | stafford- | wolff- |

| benjamin- | peto- | northcot- | drummond- |

| sir- | sir- | sir- | sir- |

| westminst- | survey- | northcote- | portsmouth- |

| metropolitan- | spithead- | miscellan- | mission- |

| halls- | fort- | words- | constantinopl- |

| bridg- | approv- | minut- | gibraltar- |

| bridge- | discussion- | accounts- | errington- |

| exet- | finsburi- | glad- | diplomat- |

| sewer- | burial- | bombay- | admiralty |

| works- | suggestion- | drawback- | bryce- |

| toll- | fortif- | westminst- | conference- |

| plans- | forts- | impress- | convent |

| seen- | works- | gas- | secretari- |

| marylebon- | inch- | nomin- | granvill- |

| statu- | central- | balanc- | maceo- |

| determin- | arsenal- | introduct- | consul- |

| kneller- | undertak- | custom- | dockyard- |

| nottingham- | complet- | explained- | consult- |

| metropolis- | portsmouth- | contemplation- | constantinople- |

Table 7: Excerpt From “Conservative Party Agenda Topic” showing decades in which technology appears: 1850, 1860, 1880 (partial); Technology-related words are in bold

Here is another instance of “checking” how the topic fairs against another conventional theme in British history – the story of party politics. I wanted to plumb the depth and breadth of what the topic models could do for our understanding of infrastructure, and so I began to add new angles of interpretation of the infrastructure story, each corresponding to a topic model where some mention of technology could be found. In effect, the organization of the article here follows my methods of research: I had a gigantic folder of all 500 dynamic topic models of Hansard, and I keyword searched the folder for each of two dozen words from a list of terms in the history of technology, selecting the topics that appeared most frequently. This kind of search was done by hand – or rather by using Google Docs – rather than using any kind of code, although I could have used code to automate it. This research project dates from before I started writing my own code, so I was interested in relatively simple kinds of searches that would help me to understand the range of ways that topic models could enhance my understanding, as a scholar of infrastructure, of the conversations in which infrastructure occurred.

Here I found myself, as someone who had researched the history of infrastructure through traditional archives, rather amazed at what I was finding. I would never have contemplated writing a book on party alignments and technology over the entire nineteenth century, so vast is the topic; one would have to have a thorough command of the allegiances of speakers, the direction of party and intellectual history, and the history of sewers, bridges, and naval warfare, alongside my expertise in roads and post, to make any headway. But the topic model, by simply grouping like words with like, produced a topic model of liberal subjects and another of conservative subjects, and each referenced certain kinds of technology. Here was a thesis that would be worthy of an entire article or even book in the history of technology – one that might have taken a decade to aggregate by traditional means – that simply emerged from close inspection of the topics.

Another topic handles the conservative party agenda. The majority of words in this topic are names of major conservative party figures. References to technology, infrastructure, and the built environment are few. However, a few moments emerge as significant: first 1850, when conservatives became involved in debates about the rebuilding of Westminster, the sewers, and the improvement of the urban environment; then 1860, when debates over gasworks, burial places, and fortifications at Portsmouth and Spithead; and finally 1880, with a discussion of dockyards.

| 1830 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1870 | 1870 | 1880 | 1880 | 1880 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ewart | liverpool | lunat | spooner | diseas | survey | canal | diseas | |

| cordial | inhabit | asylum | warwickshir | foot | complet | train | suez | cattl |

| approv | benett | pauper | maynooth | disease | surveyor | acceler | company | anim |

| gladston | toxeth | asylums | kensington | mouth | works | fawcett | agreement | foot |

| intention | park | confin | purpose | anim | ordnanc | convey | lessep | mouth |

| sound | manchester | workhous | answered | pleuro | map | steamer | traffic | disease |

| tobacco | salford | lunatics | exhibition | pneumonia | soon | north | concess | contagi |

| contended | manchest | ashley | birmingham | privi | completed | arriv | de | privi |

| maintain | merchant | visit | lesse | stamp | scale | car | navig | outbreak |

| constituents | dock | insan | enfield | animals | lloyd | postal | isthmus | slaughter |

| proprieti | port | patient | chaplains | contagi | passeng | mails | director | duchi |

| galleri | corrupt | crimin | burlington | slaughter | inch | holyhead | ulster | animals |

| satisfact | wiltshir | treatment | exhibit | affect | certif | western | bourke | pneumonia |

| amendments | packet | workhouses | promis | compulsori | shipown | servic | exclus | infect |

| liber | merchants | liverpool | ventil | infect | staff | perth | neutral | pleuro |

| full | separ | sent | romish | farm | jenkin | run | construct | prohibit |

| stage | canning | patients | gold | meat | surveyed | improv | lesseps | lancaster |

| futur | gladston | erect | cullen | barclay | possible | packet | share | affect |

| hours | huskisson | cure | resolution | stringent | noel | postmast | regent | dodson |

| best | sign | lunaci | endow | spread | gerard | tender | confer | agricultur |

Table 8: Excerpt From “Liberal Party Agenda Topic” showing parts of decades where technology appears: 1830, 1840, 1850, 1870, 1880 (partial);Technology-related words are in bold

Liberal party discussions, by contrast, concern technology, infrastructure, and the built environment far more regularly. In 1830 they are already flocking to discuss parks, the National Gallery, and the importance of England’s expanding docks. In 1840, they are concerned with lunatic asylums, pauper asylums, and workhouse reform. In 1850,while Conservatives fight for the rebuilding of Westminster and the sewers, Liberals were concerned mainly with the Great Exhibition. In 1870, we find a conversation about the reform of slaughterhouses and the regulation of farm animals to prevent pneumonia and foot-and-mouth diseases, alongside another conversation about the ordnance survey. In 1880, the conversation about cattle diseases continued, alongside a new interest in the Suez Canal, the post office, and mail packets and trains.

Summing up then, we see an ongoing Liberal interest in infrastructure and the built environment, including the dockyards and post as necessary systems for continued economic development. The Conservative interest is mainly limited to fortifications, improvements to parliament’s meeting place, and to protecting private property.

These differences give excellent support to recent histories such as John Broich’s London Water, which investigates the “conservative ecology” of figures such as Lord Salisbury, who defended the private water companies and private property rights against the attempted creation of a public utility in water by socialists such as Sidney Webb. Well before 1880, when Broich stages his battle, conservative interest in the built environment was limited mainly to questions of defense. Having advocated for the creation of a massive state bureaucracy of postal infrastructure, commercial docks and telegraph system, the Liberal Party remained committed to infrastructure systems for the remainder of the century.

We have in topic modeling a key to recognizing party divides in infrastructure, and looking for turning points as well as generalizing about long-standing party differences.

Imperial Infrastructure

This article takes the form of what I would call a “proof of concept” essay rather than an essay in argumentation. It is mainly centered around introducing the topic model to the field of the history of technology. The organization of the essay as a whole follows from this focus: thus the article opens with a literature review on the topic model, and the sections that follow apply the topic model to a range of questions in British history, asking the same question: does the new method have anything new to teach us about this subject?

In recent years, digital historians have become more aware of the importance of historical argumentation, thanks in part to the White Paper on Argumentation organized by scholars at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media in 2018. If making a historical argument had been foremost for this version of the article, it might have begun with the next section, where I introduce the idea of “complementary landscapes” – that is, the argument that British empire proceeded in many of its colonies by building parks and universities as “complements” to the prisons and barracks it built in other generations. Because park-building and prison-building seem to dominate for periods of roughly twenty to thirty years, topic modeling is ideally suited to discovering how habits of building out empire are structured over time - a feature of imperial experience that is otherwise invisible to historians.

Let us test how far topic models can illuminate the history of empire. If we go looking for empire across topics, we can perform a study in the shifting discourses that comprised discussions of imperial infrastructure.

| Roads & Gaols | Marine Regulations | Piers, Prisons, & Barracks | Railway Regulations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 1870 | 1870 | 1870 | 1880 | 1880 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 |

| counti- | anderson- | loss- | coast- | war- | coloni- | gorst- | railway- | railway- |

| county- | glasgow- | sea- | slave- | secretari- | colonies- | chatham- | construct- | construct- |

| counties- | disapproved- | life- | gold- | finaci- | cape- | secretari- | western- | western- |

| coron- | secretary- | seamen- | africa- | volunt- | australian- | received- | traffic- | traffic- |

| rates- | names- | shipown- | west- | troop- | australia- | john- | companies- | uganda- |

| middlesex- | factori- | save- | traffic- | brodrick- | colony- | sworn- | **uganda- | station- |

| lieuten- | bet- | insur- | east- | artilleri- | imperi- | bengal- | highland- | canal- |

| courts- | burgh- | lost- | zanzibar- | ordnanc- | queensland- | burmah- | guarante- | railways- |

| hertford- | objection- | marin- | slaveri- | guildord- | secretari- | bombay- | station- | northern- |

| cork- | complet- | marcantil- | suppress- | store- | emigr- | consideration- | railways- | north- |

| turnpik- | want- | unseaworthi- | ashante- | surrey- | confer- | viceroy- | canal- | passeng- |

| clare- | affairs- | live- | territori- | soldier- | island- | possess- | servant- | accid- |

| gaol | unfair- | boat- | nativ- | arm- | guinea- | rubi- | north- | companies- |

| mayo- | investigation- | sailor- | sultan- | transport- | conference- | expect- | passenge- | southern- |

| represent- | advertisements- | respons- | settlement- | afghan- | jamaica- | despatch- | northern- | midland- |

| chester- | brazil- | ships- | circular- | contraband- | canada- | corrobor- | carriag- | mile- |

| mile- | maltes- | caus- | african- | barrack- | western- | sir- | accid- | engin- |

| road- | necessary- | sustain- | king- | hanburi- | morgan- | rs- | midland- | carriag- |

| constabulari- | navig- | danger- | slavery- | manufactur- | zealand- | replied- | extens- | servant- |

| poll- | bad- | safeti- | station- | royal- | osborn- | nizam- | company- | travel- |

Table 9: Topics Where Empire Appears; Place names and technology-related words are in boldface.

Comparing different decades where infrastructure appears across topics can help the scholar to generalize about large-scale shifts of construction and building across empire. Table 8 brings together excerpts from four different topics that handle both empire and technology: “Roads & Gaols,” “Marine Regulations,” “Piers, Prisons & Barracks,” and “Railway Regulations.” The topics reveal a shifting pattern of geography. In the 1840s, parliament’s major concern with empire was in the debating of Ireland, where the infrastructure concerned was mainly roads and jails. In the 1870s, empire turns up in a topic about marine regulations – mostly discussions of ships and fisheries – which now included debates about slavery off of the gold coast and how life insurance for sailors lost at sea should be handled. In the 1880s, we see a shift to conversations about barracks and troops in the Cape, Jamaica, New Zealand, and the Subcontinent, where the technology in question is mainly that for housing troops. By the 1890s, the discourse of managing empire again shifts, appearing in a topic largely about railway regulation, where the railways in Uganda are apparently being discussed in the same terms of passenger safety and financial guarantees as those in the midlands. Dynamic topic models sketch for us not only the shifts of geographical attention that marked the imperial experiment, but also how different geographies were approached within different technological and architectural systems.

Topics in this case draw our attention to the prevalence of barrack- and prison-building as a mode of imperial infrastructure. One topic, which we have labeled for our convenience, “Communications Around Empire,” shows much the same structure as the Post Office topic with which we began: a preliminary structure, in this case where parliament debated transportation and the need for vessels to transport convicts and troops to guard them, was interrupted in 1860 by the adoption of the telegraph. We see throughout the period not a persistence of an administrative bureaucracy, but instead the persistence of troops and prisons meant to contain insurrection, and for which the telegraph later became vital. Dynamic topic models help us to generalize about the pattern of technology over time.

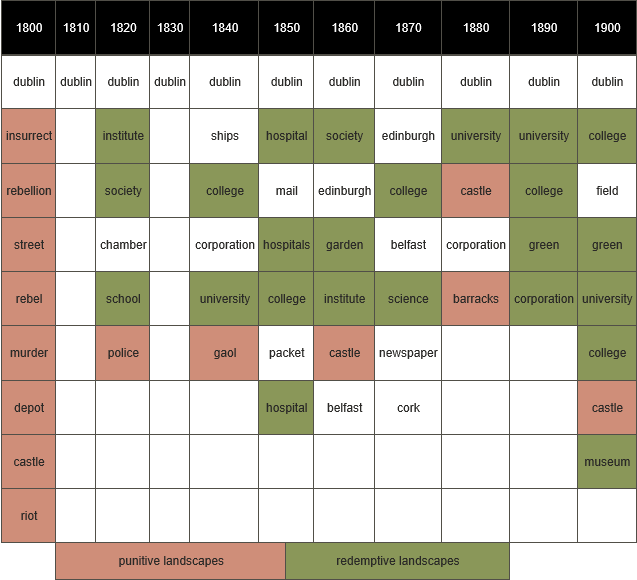

Generalizations such as these also allow us to contextualize particular prisons against a wider backdrop of imperial building. Another topic that is purely imperial concerns not Bengal and Uganda but the imperial cities of Dublin, Edinburgh, and Belfast, which became sites of regulation and construction during the nineteenth century (see Table 9). In 1800, the “Imperial Metropole” topic is bound up with discussions of insurrection, rebellion, riot, and murder. By 1820, we see a shift in parliamentary debates about Dublin to discussions of beneficent infrastructures: the building of institutes, schools, hospitals, and gardens; the religious integration of universities and colleges; the promotion of science. The police state does not disappear, of course; about every twenty years, parliament would renew its attention to police, jails, and the Castle specifically in Dublin and Edinburgh.

The context lent by the topic model helps us to understand the structural relationship between Kilmainham Jail, where Britain kept its political prisoners, and the public parks of Dublin. Dublin’s parks were demonstrations of imperial munificence. But in the struggle for Irish independence, the parks also became sites of violent encounter. Phoenix Park, originally a private hunting ground opened to the public in 1745, became in 1882 the site of a double assassination of the newly-installed Secretary General of Ireland and his under-secretary by Fenian terrorists. St. Stephen’s Green, originally installed in 1880, became, in Easter 1916, the site of trenches from which rebels launched their attack.

Parks of course are strategically useful for a guerilla occupation of the city, as they are publicly accessible spaces where the governing class and the governed met. As demonstrations of imperial infrastructure, however, the parks also served a poetic role as indicators of Britain’s civilizing agenda. Irish Fenians attacked infrastructure directly in Canada where they bombed the trains, and in New York City, where they attacked piers. In closely-guarded Ireland, however, attacking the infrastructure of communications was more difficult. Attacking the parks, however, offered a symbolic opportunity to threaten the infrastructure of beneficence.

Topic modeling reminds us to contextualize these attacks on parks against the pattern of building over time. Over the whole of the nineteenth century, building parks to advertise Liberal Britain’s civilizing mission alternated with the installation and expansion of a punitive architecture of control. Attacking the Kilmainham Prison might have been beyond the strength of Irish resistance, but attacking parks was its symbolic correlate.

Table 10:

Punitive and Redemptive Landscapes of Technology in Colonial Dublin, Belfast, Cork, and Edinburgh, from ‘Imperial Metropole’ Topic.

Table 10:

Complementary Landscapes

If prisons and gardens form obverse sides of one system of imperial architecture in Dublin, it stands that one potential use of topic models is to find other such hidden relationships between different parts of the built environment. One place where relationships such as these emerge is a topic that we have labeled for convenience, “Managing the Children of the Poor,” a topic that reveals the shifting discourse (highlighted in mustard) about the reasons why parliament must intervene to protect the children of poverty, from illegitimacy in 1830, to vagrancy in 1860, to blindness and parental neglect in 1880, to underfeeding in 1900.

Table 11:

Managing the Children of the Poor.

Here, as with the “Imperial Metropole” topic, we see an alternation over time between decades where dark red predominates – a punitive discourse about regulating factories and creating workhouses – and where blue predominates – a salvific discourse about education, schools, reformatories, and later, compulsory education, vaccination, and nutrition, which comes to dominate the conversation after 1870. Again, the dynamic topic model foregrounds changing discourses. In this case, however, the probability model upon which the dynamic topic model is based should be interpreted as underscoring the fact that workhouses, factories, and schools were intensely debated with the same language, indeed often in the same debate. The school, factory and workhouse are thus what we are calling “complementary landscapes,” places that are exactly the same insofar as they were shaped by parliament into solutions to the problem of poverty imagined as a crisis of children abandoned by their parents to an early life marred by illegitimacy, vagrancy, and malnourishment.

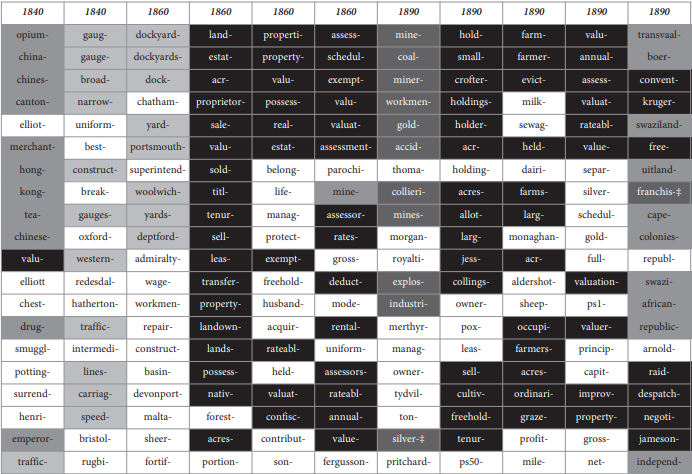

Table 12:

Excerpts from Topic, ‘Things Taxed and Regulated’; Light shading = Communications; Dark Shading = Empire; Darker Shading = Mining; Darkest Shading = Land Reform

A final set of insights pertain to expanding our review of dynamic topics from technology and infrastructure to landscapes and materiality more generally. In Table 11, t topic, “Things Taxed and Regulated,” is extremely vast, handling 205 columns of various items discussed in a similar language of assessment, value, inspection, and regulation. In this topic we read about the regulation of opium in China in the 1840s; the debate over narrow and broad gauge rails and railway speed in the 1840s, and mines in the 1860s, as well as dockyards for the repair of admiralty ships; by the 1890s, mines for gold and silver in the Cape and Transvaal are the subject of debate. From the 1860s, we see a burgeoning conversation about assessment schedules, qualified assessors, and the rental of land and mines: evidence of an expanding bureaucracy attempting to keep pace with the taxes required to sustain imperial infrastructures elsewhere. Thus the landscape of regulation (including the mines and the railways) can be understood as the complement of the landscape of taxation (newly and particularly assessed tenancies and leases).

This brings us to our final use of the topic model. The political scientist Karl Polanyi theorized a famous “double movement” of capitalism, where the ravages of capitalism are such that society requires the state to expand in defense of those who have suffered from dehumanization in capitalism’s wake. In a final view of this last topic model, we can see the broadening standardization by the state of the transport landscapes of railways and dockyards (in red) is connected to a landscape of capitalist exploitation in the form of mines (in yellow) in a shifting imperial geography from Hong Kong to India to Africa (in blue). The complement of these landscapes is shown (in gray) to be the smugglers and estates coming under increasing parliamentary inspection for the purposes of an effective and regularized taxation. But there is another discussion, more pronounced in the 1890s; the political complement to these extractive industries of different kinds: the discussion of allotment gardens, smallholdings, and crofts defended by radicals in parliament from the 1890s. This last complementary landscape represents Polanyi’s “double movement,” realized against the extractive landscapes of capitalism and empire: discussed in the very same spaces and language of assessment, value, and possession as were the dockyards and mines. We have, in miniature, the landscape allegory for the crisis of capitalism that gave birth, through land reform, to the socialist nationalization of land, transport, and industry, setting up Britain in the twentieth century for a clash between the anti-bureaucracy Conservative Party and the pro-infrastructure members of Labour.

Discussion: Testing the Method Against Existing Historical Consensus

Prior consensus is important to testing whether a new method has indeed contributed new knowledge. The background to this study is the historiography of technology, infrastructure, and landscape in empire. Historians of Britain, India, Australia, and Africa have concluded that the technologies of global trade brought with them regimes of surveillance and control, all presented with the patina of rational enlightenment. These forces irrevocably changed the everyday landscapes of Britain and its empire on six continents. Generally this story is told in five parts: first, there’s a story of mapping and surveying, especially of the subcontinent, Australia, New Zealand, and the Cape, in such a way as to make native lands more easily taxed.16 Secondly, there’s the guarantee system of railroads in India and Canada from the Dalhousie Minute in the 1840s, which at least in the case of India, punished native industry by charging higher rates for shipping from the ports than to the ports.17 Third, a private system of railroads on the continent, and in North and South America, was surveyed by British surveyors, built by British engineers, and funded by loans from British banks, which enriched British pockets.18 Fourth, a system of gunboats, superior guns, telegraphs, and railways that allowed Britain to suppress conflict wherever it emerged.19 Finally, imperial connections, including the handing over of the Suez Canal from French to British control and the rise of railways in Africa, the creation of harbours in Cyprus and lighthouses around the world.20 We might refer to these propositions collectively as “the guns, maps, and steel thesis of imperial infrastructure.”

Generalizing about diverse events of this kind is not easy, particularly when the historian regards an era of building at immense scales like that typified by the creation of London’s dockworks in the 1790s, or the ship building works of the 1880s, and in between, thousands of little-documented trunk roads and regional rail corridors. Calculating the expense and extent of these networks of communication is daunting for the student working one archive at a time. The labor that would be required to simply compare expenditure of railroads on a global level – to answer, for instance, the question, What was the most expensive railway in all of empire? -- would be staggering. As a result, scholars have traditionally avoided having to answer such questions.

The result is storytelling in the key of tradition, using the pattern of memory established by earlier historians to inform the choice of research subject. We handle an individual canal like the Suez as proxy for the networks of infrastructure as a whole because the process of learning about all canal building around empire would be hopelessly tedious. The guns, maps, and steel thesis of imperial infrastructure leans heavily on an earlier generation of historians of empire around the turn of the nineteenth century as sources highlighting principal events such as the Dalhousie Minute (a political circular) and the forging of the Great Theodolite that measured India (an event of engineering with colonial consequences) or the opening of the Suez Canal (an event of engineering with intercontinental political and economic consequences). The choice of which events are studied is essentially outsourced to historians or writers in the past; the job of the historian in the present is to analyze those events, but not to critique which events were chosen. This outsourcing is a necessity of the sheer volume of unread material: an inestimable challenge to the labor and discipline of even the most energetic historian.

The problems of synthesis are exactly what make text mining such a rich supplement to our archival encounters with individual cases. The use of this method has suggested added context to known events in the history of technology, for example the sustained history of party differences over infrastructure that preceded better-known instances of state backing of technology.

In the foregoing examples, topic modeling has illuminated new patterns of parliamentary engagement with infrastructure: conservative and liberal, naval and army. It has even helped us to understand how infrastructure was structured around a relationship between complementary landscapes that appeared repeatedly within the same debates over management of empire and poverty: parks and prisons are one such node; factories, workhouses and schools are another; and mines, railroads, and land reform a final such node of repeated engagement. The analysis of history from a distance – from Apollo’s eye – enables new groupings such as these to emerge from the data itself, interpreted by the scholar already familiar with existing historiography. They enhance our skills at critiquing received research subjects and existing categories. Perhaps even more importantly, they illuminate under-researched episodes in history, making room for new macrohistorical research that can shape our understanding of the larger context, as I shall explain in my conclusion.

Conclusion: Towards the Blending of Microhistory and Macrohistory

The examples of enhancements delivered by topic modeling include the illumination of particular events that have escaped major attention in the history of technology. For instance, the River Shannon appeared early in this article, highlighted by a topic on “River Improvement,” where the Shannon was ranked in an unexpectedly high place besides the Thames. Comparatively little scholarship has covered the improvement and technology of the River Shannon. However, over the course of the nineteenth century, the Shannon was mentioned 1,214 times in Hansard, in comparison with 3707 mentions of the Thames, 2,134 of the Nile; 853 of the Clyde, 809 of the Trent, 280 of the Severn, 186 of the Liffey, and 5 of the Ganges.21 The River Shannon was indeed the target of parliamentary money for improved navigation in the 1830s and 40s; it was embanked and drained for Limerick in the 1860s; eel weirs and salmon ladders were designed for it in the 1860s, making it an early subject of environmental engineering; parliament regularly inquired into the flooding of the river after its embankment and the rights of poor fishermen; and by 1910 a plan for hydroelectric power from the Shannon was being mooted.22 That the River Shannon in Ireland shows up as a target for so many discussions of infrastructural improvement is unexpected given the relative lack of historical scholarship on the subject. Historians have spent far more attention on the river infrastructure in London, which is associated with cholera, the Great Stink, Joseph Bazalgette, and the Embankment.23

In the section that follows, I turn towards one of the findings of my research with topic models of a kind that it is often assumed new methods should produce: a wholly new and surprising fact of history. I set out two of the historical insights that can be gained by topic models that reveal information which has hitherto not been a subject of historical analysis. Either of these subjects – Robert Crawford or the River Shannon – could be expanded upon as the subject of historical research either by methods distant or close, or ideally perhaps by a combination of the two. Should the essay have begun with them, therefore? Should a digital history essay make an argument about how Robert Crawford or the River Shannon was a fulcrum of history?

My assessment is no: both Crawford and the River Shannon are ideal subjects for some later researcher to follow up on. What the topic model tells us about is the fact that each of them participated in a larger pattern of historical change. The article foregrounds several instances of the kind of historical change that can be identified through topic modeling. But topic modeling, in itself, does not give us much original detail about either Crawford or Shannon. It would be appropriate to follow up on each through a combination of traditional techniques – like reading primary materials associated with the story of each – and distant techniques like looking for the context in which each appears, perhaps using word embeddings or grammatical triples over time. Obviously those techniques are outside of the domain of a paper organized around topic models.

Similarly, a dynamic topic model on the Post Office turned up reference to “Crawford” alongside the more expected names of John Palmer and Rowland Hill, the postal reformers, or George Eden and Pitt the younger, who examined their contributions. The Crawford in question turns out to be Robert Wigram Crawford, whose name signals the importance of the Select Committee that challenged the private monopoly of the Pacific and Oriental Steam Navigation Company over the telegraph connection to India in 1866.24 As with the River Shannon, the topic model recovers the memory of a little-regarded event of significance in its own time.

The insights gained from the Shannon and Crawford examples are typical of the insight that one hopes for from topic modeling: the computer reveals, in most cases, less a massive miscategorization of an entire era, and more frequently, a small insight about a topic of debate that was important in its own context and has since been forgotten by scholars. With the help of the topic model, the historian attempting to synthesize important turning points in the history of imperial infrastructure may redirect her gaze to the relatively little-known literature on the Shannon, the majority of which are published in venues relating to Irish history, or into close studies of the Pacific & Oriental Telegraph Company.25 In this way, microhistorical scholarship around significant subject matter that has been judged chiefly of local interest by the scholarly community may be brought to light. The topic model is in this sense a useful corrective to historical surveys of a period, as well as a generator of new possible research ideas for scholars and students.

It is clear that a macrohistorian armed with digital tools must nevertheless draw insight from microhistorical studies of particular technologies, individuals, and events to illuminate her narrative. However, it is equally true that digital studies on the longue durée have much to offer the microhistorian,, who may borrow from digital scholars, learning from topic models and similar tools the context that will help her explain the overall significance of a particular technology, individual, and company to a global scale. Microhistory and macrohistory should work together, each offering a method of insight into event and context in the past.

This paragraph is where I take time to reflect on the genres of criticism in the digital humanities – in part with the idea of pre-empting readers who might be accustomed to reading in-depth treatment of a single theme across multiple primary sources. In the research that forms the basis of this article, the visualization or the topic model becomes a kind of source in itself, wherein the scholar can study the flow of time through careful reading and comparison of topics. The method, and even the document base, are thus entirely new, as are the historical findings that result from this process. But the scholar’s careful, critical attention and comparative technique of putting sources side-by-side for examination and reflection are a method as old as the hills.

This article has advanced a method chiefly of use for comparing the categories of discourse across time periods. Seeking to explore only the method itself -- how a topic model can point the researcher to significant contexts – we have seen that dynamic topic models indeed are useful for highlighting t moments of shifting technology, institutional alignments, and political structures in the landscape. For this purpose, we have intentionally limited ourselves to reading the topic models themselves. In a more sustained study, the contextual enhancements of the topic model would act like a particularly well-gardened card catalogue, directing the researcher to names, places, keywords, and dates that would illuminate the parallel events we have found, the changing discourses, and the complementary landscapes. Such a study would surely be of interest to historians of technology and of empire more generally.

-

Sidney Webb 1859-1947. and Beatrice Webb 1858-1943, joint author, English Local Government: The Story of the King’s Highway (London,: Longmans, Green, 1913); Philip Sidney Bagwell, The Transport Revolution from 1770 (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1974); Derek Howard Aldcroft, British Transport Since 1914: An Economic History (North Pomfret, VT: David & Charles, 1975); Derek Howard Aldcroft, ed., Transport in the Industrial Revolution (Manchester: Manchester Univ. Press, 1983); Chris Wrigley, John Shepherd, and Philip Sidney Bagwell, On the Move: Essays in Labour and Transport History (London: Hambledon Press, 1991). ↩︎

-