What, Where, When and Sometimes Why:

Data Mining Two Decades of Women’s History Abstracts

Citation for Original Article:

This piece originated from David Newman’s work in then-brand-new technology of probabilistic topic modeling. Sharon Block quickly saw the potential value in this massive data mining tool for historical analysis and the two successfully received funding from University of California, Irvine to undertake several case studies. Sharon’s interest in sexism in the historical profession led to this analysis of the place of women’s history in historical publishing. Because full text journals were not available, we turned to (what were then) widely-used database abstracts that covered historical publishing from c. 1450-present.

One of the challenges of the piece was satisfying reviewers. While this is true of all peer-reviewed scholarship, in addition to many helpful critiques, some reviewers were not sure how to evaluate this interdisciplinary work. Some seemed to view it as outsiders writing about women’s history (double blind review meant that readers did not know that one author very definitely considers herself a women’s historian), some misunderstood how topic modeling works, and as a whole, reviewers disagreed on the ideal purpose of the essay. The title aimed to signal that while we address issues relevant to current historical debates, our primary focus was to explore, not necessarily explain, the patterns we newly identified. Our idea was that this piece would provide hard data as an impetus for others to do further investigation into sexism in historical publishing.

Scroll down to see the annotations.

Setting this piece within the context of debates in women’s history was important to me – especially because one of the early readers believed that the authors were computational interlopers who did not know or care about the field.

In the past half decade, prominent historians have quantified scholarship on women’s history to analyze the state of the field. In a 2004 publication, Gerda Lerner tallied 720 recent U.S. women’s history articles, books and dissertations from the Journal of American History’s list of Current Scholarship by time period and theme. In her 2006 book, Judith Bennett quantified scholarship in various women’s history journals and conferences to show an overemphasis on more recent time periods. In 2007, Merry Wiesner-Hanks analyzed the regional focus of Berkshire Women’s History Conference papers and Journal of Women’s History publications in her essay on the place of women, gender and sexuality in World History.1 Other scholars have published state of the field pieces that provide qualitative analyses of women’s and gender history.2

It took three years from submission to publication (partly due to editorial turnover) which meant that the scholarship under review was already more outdated than I would have wanted at publication – ending in 2005 for a 2011 article. It was not possible to retroactively include abstracts later than 2005 because redoing the topic models would have meant starting from scratch.

This article is clearly structured around data analysis, as represented in tables, charts, and graphs. But in an indication of one of the difficulties of stretching beyond traditional disciplinary methodological boundaries, the original copy editors did not realize there were 16 images that went with the article. This was far beyond the journal’s standard maximum number of figures of 3-4 per article which meant I had to get editorial permission to publish an article with that many figures. The permission was not difficult to get, but did strike me as an indication of how far outside the mainstream this kind of data representation was for this women’s history journal.

Quantitative and qualitative analyses provide these women’s historians with a sense of the developments in much of our field and point to remaining shortcomings and opportunities. This article builds on the desire to understand the scope and achievements of women’s history by providing a more comprehensive quantitative overview of the place of a large segment of women’s history within a large segment of historical publishing between 1985 and 2005. Our analysis examines more than a half million abstracts from two widely used article databases that cover historical study since c.1450. We use these to explore the place of women and women’s history within the historical field in general, and within regional and chronologic subfields in particular. While women’s history reflects some overall shifts in the historical profession, it also has a demonstrably separable trajectory in terms of its expansion, content, and regional/chronological foci.

While topic modeling has not seen widespread use in women’s history, in 2014, the feminist journal Signs used topic modeling to build an interactive tool to interrogate its past forty years of publications (“Signs @ 40 1975-2014,” http://signsat40.signsjournal.org/topic-model/

We then move to exploring the approximately 31,000 abstracts that we identified as women’s history-focused. We look at shifts in article publication patterns between 1985 and 2005 to see how the field has – and has not-- changed. We directly explore the content and range of post-c.1450 women’s history across these two decades, and question whether a seemingly more twentieth-century focus of women’s history is a by-product of overall developments, a more complicated transformation, or less of a shift than it might originally appear. We also track the regional and chronological subject area variations within women’s history abstracts, and suggest that this be a starting point for discussions of the place of women’s history within various subfields. In the paper’s final section, we select a single topic area – sexuality -- for deeper analysis. We identify broad subject areas covered within sexuality histories and trace their variations across time and place of study, suggesting the value of this kind of quantitative exploration.

I originally envisioned this as a proof of concept or case study exercise that showed the value of topic modeling to the field of women’s history; an area of inquiry that is known for innovative but often not quantitative methodological innovations. Even in 2008, it seemed clear to me that feminist scholars were not recognized players in data mining and massive corpus analyses. For these reasons, it was important to me to do research that married data mining to feminist analysis.

Thus, as our title suggests, we are addressing several “whats, wheres, and whens” of two decades of post-c.1450 women’s history: what place does women’s history have in the field at large and what kind of subjects are included within women’s history; where in various regional histories does women’s history most frequently appear; when do publications on women’s history increase or decrease in numbers as well as when, chronologically, women’s historians most focus their efforts.

This paragraph was meant to answer conflicting reader recommendations to frame this essay as a state of the field report versus an analysis of the causes of sexism in historical publication. I decided to be upfront with both the aims of this piece, and with what it did not accomplish as a way to manage readers' expectations.

The “sometimes why” is a more complicated venture. At various points we forward possible explanations, grounded in historiographic scholarship, for the trends we have identified. But for the most part, our broad analysis of tens of thousands of abstracts at a time, aims to recognize basic patterns that raise as many questions about the constitution of the field of women’s history as they answer. We mean this article to start a conversation about women’s history as revealed through a large-scale quantitative analysis that provides hard facts, rather than qualitative impressions, about the field. We conclude by proposing questions about how we can benefit from this type of interdisciplinary collaboration, what it might suggest about how we understand the place of women’s history in the field, and the role of the profession and academic institutions in the support of various kinds of historical study.

Methodology

The methodology section shrank in revised versions of the essay because discussions of technological processes seemed to lead to confusion and, most early readers were not particularly interested in how the technological sausage was made. It was a challenge, especially when topic modeling was so new, to describe it in terms historians would understand, so we went with a citation to my 2006 historian-friendly introduction to topic modeling [Sharon Block, “Doing More with Digitization: An Introduction to Topic Modeling of Early American Sources,” Common-place: the Interactive Journal of Early American Life 6:2 (January 2006)]. We did not cite our jointly authored technical piece [David Newman and Sharon Block, “Probabilistic Topic Decomposition of an Eighteenth-Century American Newspaper,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57:6 (April 2006), 753-767] because it was not aimed at humanities scholars. Personally, I find methods discussions engaging, and would have liked to explain more about topic modeling, including topics as most frequent word lists so that readers could analyze the labels I put on them for themselves. A web supplement with all that additional information would be useful if I wrote the article today.

The main source for this article is 513,259 substantive abstracts of articles and essays published between 1985-2005 in America: History and Life and Historical Abstracts databases. America: History and Life (AHL) focuses on the history of the geographic regions that now make up the United States and Canada. Historical Abstracts (HA) covers the history of the world outside of North America from approximately 1450 onward. Some of the most widely used abstract databases in the historical profession, AHL and HA include English and non-English language publications, and gather historically-oriented articles from more than 3,000 scholarly journals, including women’s studies publications. These databases are not perfect representations of the historical profession by any means -- the exclusion of pre-1450 scholarship may be one of the biggest handicaps -- but they still provide a much larger corpus of information than heretofore examined.

Word frequency counts, though hardly an innovative method, proved to be useful in doing a feminist analysis of the half million historical abstracts. On various issues, we determined that a frequency count might support an analytic point more clearly than topic modeling. This was an excellent reminder that the newest, snazziest technological innovations don’t necessarily yield the best results in every situation.

Footnote 5 was added to try to further explain probabilistic topic modeling after one reader wrongly suggested that our “database” needed significance tests.

We analyze this collection of abstracts using two main methodologies. First, word frequency counting (how often a given word occurs) reveals how and when terms related to women appear in historical abstracts.3 Second, topic modeling, a computer science data mining technology that is arguably the state-of-the-art model for text document collections, allows for a more complex subject analysis.4 Topic modeling learns subject categories without a priori subject definitions. Unlike traditional classification systems where texts are fit into preexisting schema (such as Library of Congress subject headings), topic modeling establishes a comprehensive list of subjects through its analysis of the word co-occurrences throughout the corpus. The content of the documents—not a human indexer—determines the topics collectively found in those documents, arguably making topic modeling’s subject indices far more sophisticated than human classification.5

At the time I wrote this, debates raged (as much as they could “rage” in a pre-social-media era) on the distinction between gender and women’s history. Hence this explanatory paragraph.

Throughout our analysis, we employ a broad definition of women’s history. We include work that focuses on individual women, on women as a group or groups, and on the power dynamics of patriarchy that some have shorthanded with the term “gender.” We do not single out feminist scholarship from that which addresses women’s experiences without an interest in patriarchal power structures. In short: we use “women’s history” expansively, to encompass all kinds of scholarship that addresses women’s lives, experiences, and the societal beliefs that surround them.

We did not want to include too many technical details about the topic modeling in the text, for fear it would alienate readers. We instead explained in footnotes that we did runs of 40-120 topics of the half million abstracts, and 20-80 topics for the c. 19,000 women’s history abstracts, then reviewed which seemed to be most useful to understanding each corpus. This would be one example of where data analysis relies on judgment as much as science.

We identified this broad field of women’s history by included abstracts that ranked highly in women’s history topics from our initial topic modeling runs; those that were published in women’s studies or women’s history journals; and those that the AHL/HA databases had given the terms of “women,” “woman,” or “gender” as a subject heading.6 Together, our combination of subject word, topic model, and women’s studies journals resulted in identification of about 6% of abstracts -- 30,891-- as being substantially focused on women’s history.

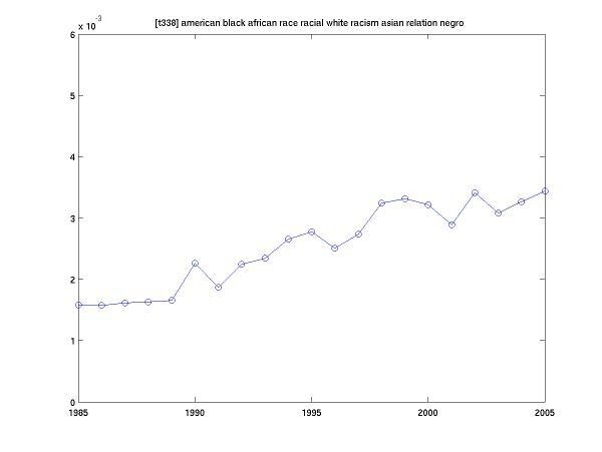

This chart, which did not make the final cut for the original article, gives an example of what topic modeling could show about change over time.The topic area that I labeled “Race” has the mostly likely words listed at top of chart and traces its increase from 1985-2005 as a proportion of all historical publications. This chart was created from a 400-topic topic modeling run of all abstracts in order to get to this level of specificity.

See also comment on The Methodological Challenge.

This table shows one topic modeling analysis of the c. 19.000 abstracts identified as related to women’s history. Because we did not focus on detailed topics for the bulk of the article, I labeled topics mostly for my own ease of identification (ie: I had two topics related to literature, and did not parse the fine differences between them for this essay). Creating a representative topic label involved parsing each list of likely words and looking at the articles with the highest percentage of text relating to each topic. If I wrote this today, I would crowd source the topic labels with multiple domain experts and provide an online supplement with transparent labels on each topic that showed areas of agreement and disagreement.

| Topic Label | T# | % of 20 | Likely Words |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, Feminism | t19 | 0.0862 | women history gender feminist feminism movement social studies political historical between historiography work research american issues review politic historian author how theory cultural class race |

| Labor | t11 | 0.0842 | women labor work gender social employment economic worker working men class male female domestic roles industry status policy sex welfare union organization role home position |

| Sex Roles | t4 | 0.0700 | women men roles female new male gender social class american who century girl than many work them society during domestic role sport often some world |

| Class, Sexuality, Gender | t3 | 0.0700 | women century gender social class female men 19th middle roles public england sex male britain sexual british between victorian society masculinity domestic sexuality new power |

| Sex & Society | t2 | 0.0661 | women social law marriage sexual prostitution century legal divorce court control sexuality men public violence state sex gender against family right cases between society reform |

| Literature | t17 | 0.0612 | her mary women author she novel writer england work writing letter literary great woman elizabeth britain life margaret female poetry his english century william wollstonecraft |

| Suffrage, Feminism, Politics | t9 | 0.0557 | women political movement suffrage right social politic feminism feminist woman party organization national reform new irish association state jewish union equality campaign ireland league who |

| Family, Social & Economics | t10 | 0.0532 | women family household marriage men children economic social families than married single between canada among mother age data female labor gender sex who widow support |

| Family, Kinship | t15 | 0.0459 | family household families century inheritance marriage social new member children generation kinship property economic rural son land pattern relationship between england one early 19th among |

| Literature I | t12 | 0.0450 | her life she family letter who mary his author husband virginia wife dickinson woman frontier anne daughter emily death diaries alcott massachusett louisa pioneer first |

| Civil Rights | t7 | 0.0408 | right civil black movement american action discrimination race affirmative employment racial african white act political equal equality activism south 1960 during 1964 california federal public |

| 20th C gender, culture | t14 | 0.0405 | women gender century female culture art quilt sex roles american men male how china cultural periodical popular images chinese about masculinity body 20th early fashion |

| Europe, Marraige | t16 | 0.0400 | women marriage social france century french status family des germany between und der church men 18th court life early les marriages society who law europe |

| African Americans, Slavery, Abolition | t5 | 0.0388 | women review american black history work life gender author book edited harriet century her race america literature novel slave culture new white lives beecher writing |

| Religion | t6 | 0.0383 | her she life church who woman his husband first catholic religious year mary work marie death mother mormon wife sister became france career russia maria |

| African American, Civil Rights, Black Church | t8 | 0.0383 | women her black she south woman american movement social christian southern african right civil temperance carolina union reform indian life king white work baptist mary |

| Homosexuality | t1 | 0.0374 | sexuality sexual homosexuality lesbian sex gay film male homosexual gender new cather female century art his between theater science willa work culture men body novel |

| War/Military | t13 | 0.0321 | war women world military during political peace civil france movement soldier french american roles army revolution japan national international service who japanese gender politic italian |

| Education | t20 | 0.0289 | women education canada school university teacher college student colleges universities social ontario canadian studies female teaching educational career higher science girl new gender history boston |

| Literature II | t18 | 0.0275 | her elizabeth letter britain novel author great work women writing she charlotte mary new century gilman life margaret jane writer perkin poet literary woman british |

Women’s History in the Field at Large

In retrospect, I could have punched up this opening paragraph to better convey the excitement of some of our findings. I suspect that, with such new methodologies, I was wary about stepping too far away from what I could prove to adopt a more conversational, or even slightly polemical, authorial voice.

The amount of scholarship on women and gender within the historical profession has, not surprisingly, grown since 1985. Our analysis shows that this growth has neither been steady over time, nor have particular historical time periods and regions seen equal amounts of women’s history scholarship. Judging by an array of word counts, male figures still remain the overwhelming focus of historical study. In addition, several scholars have suggested that women’s history disproportionately focuses on very recent and on U.S. history topics. Here we show that some of this concentration may actually be more a reflection of general scholarly trends than specific to the field of women’s history.

One of the most surprising findings was that even by 2005, women’s history content was still a single digit percentage of all publication abstract content. I checked these numbers ten different ways because I would have guessed that women’s history content accounted for closer to 25%; undoubtedly women’s historians were overrepresented in my own professional networks. I also asked a dozen-plus women’s and non-women’s historians to guess the percent of article publications over the past two decades that focused in some way on women’s history. Pretty uniformly, they guessed closer to 50% than the reality of 10%.

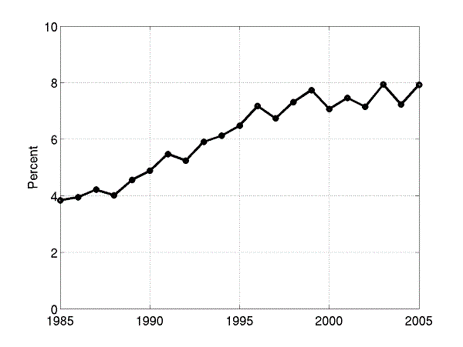

Publications related to women’s history have been increasing since the 1980s. Figure 1 shows that women’s history articles accounted for about 4% of all abstracts in 1985, and grew to about 8% by 2005. Some of this relative growth resulted from an increase in absolute numbers of women’s history publications and some from a decline in the overall number of historical articles. In 1985, about 27,500 historical articles were abstracted in AHL and HA. Of these, about 1,058 related to women’s history. By the second half of the 1990s, women’s history articles began leveling off at the 1,500 per-year mark, while history articles overall continued to decline -- to about 19,000 by 2005.

Looking back on this, I’m still surprised at the low percentage of abstracts that contain any substantive content on women’s history. I would love to repeat this to look at 2006-2020 to see whether the percentage of women’s history content has changed in the last decade and a half.

I provided multiple ways for readers to engage with data and tried to answer the questions that might come up from the data presentation. One of the important issues when looking at absolute numbers was how increases in women’s history publications related to changed overall publication numbers.

Despite overall increases, the growth rate of women’s history abstracts seems to have slowed significantly by the second half of the 1990s; the small relative increases after that are due to an overall decrease in historical abstracts generally, not to an increase in absolute numbers of women’s history abstracts. Do we interpret this as a positive: women’s history is becoming a bigger part of history? Or, given that women’s history-related abstracts still only account for, at most, 8% of all history article abstracts, is the slowdown in absolute numbers of women’s history scholarship a cause for concern? At the very least, we can quantitatively confirm that women’s history is not anywhere near to a majority of publications.

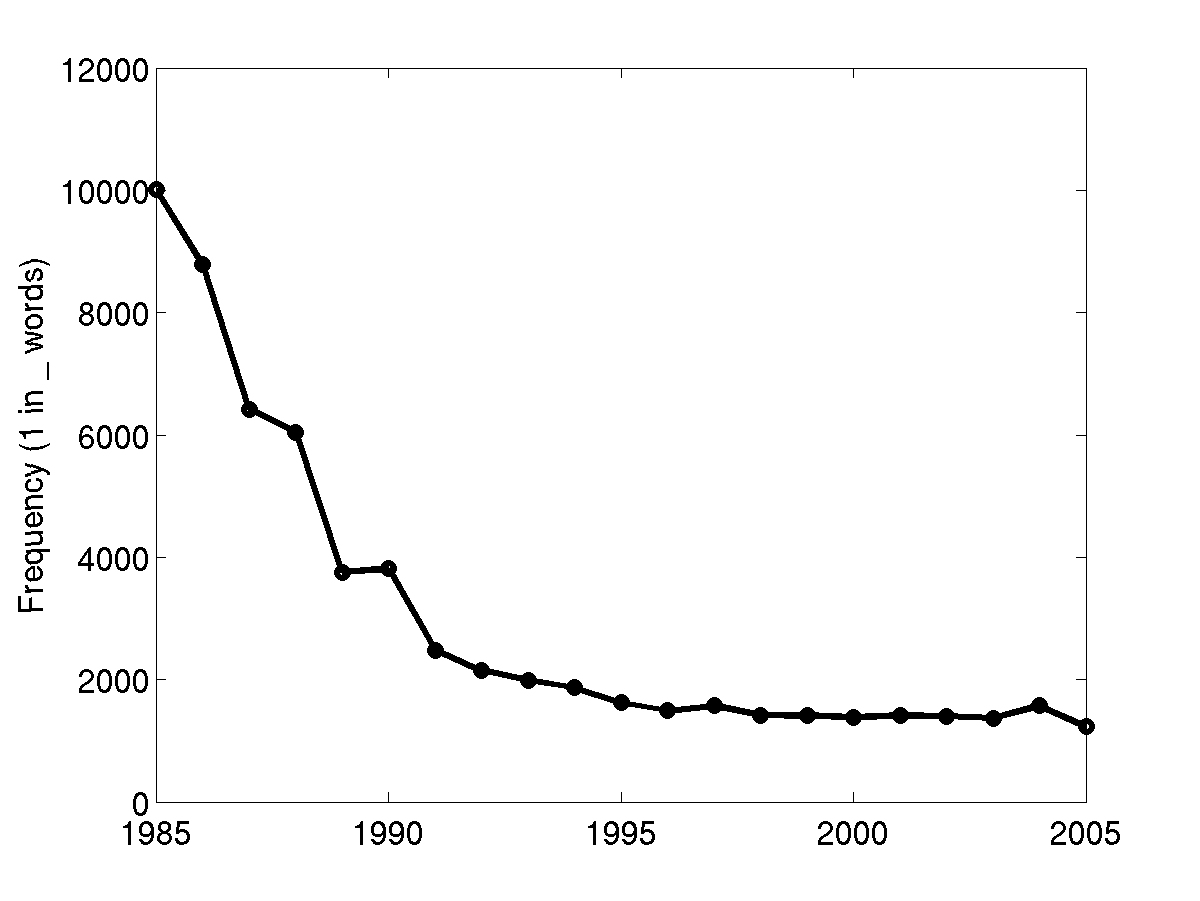

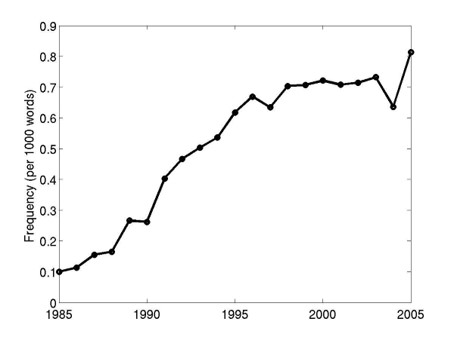

In the article’s original version, this figure was expressed as “Frequency in __ words” which produced what looked like a declining curve. For the revision, we inverted the chart to be a more user-friendly by calculating frequency per 1000 words, which created an upward curve that reflected the increased use of “gender” as a descriptive term. This was one way we tried to make the charts, figures, and math accessible to historians.

OLD Figure 2: Frequency of Mentions of “Gender” in Abstracts from 1985-2005

I tried to repeatedly remind readers that this was an analysis of abstracts, and so one step removed from the articles themselves. This was particularly important when analyzing the word frequency of “gender.” I suspect that the dramatic rise of the term “gender” in abstracts reflected shifting disciplinary jargon and may overstate a shift in the content and approach to women’s history.

While women’s history articles have been increasing since 1985, their content (or at least the identification of their content) has changed dramatically over time. Most strikingly, the usage of the word “gender” increased exponentially (See Figure 2). In 1985, “gender” occurred less than 1 in every 10,000 words in abstracts. By 2005, “gender” occurred in about every 1,250 words – an eight-fold increase. In comparison, the use of the word “women” grew by only 33% over this period. As most women’s historians know, the discussion of “women” quickly took a back seat in the late 1980s and early 1990s to the use of “gender” in historical scholarship.

Figure 1:

Women’s History Abstracts as Percent of Overall Abstracts versus Time.

Beyond tracing the historiography related to gender and the shifts toward cultural, rather than social, histories in many circles, I also wanted to note that there were costs to this beyond just a terminological shift. “Gender” wound up displacing what may have been more overtly feminist classifications like sexism, patriarchy, etc. To be clear, gender was a radical and empowering analytic tool for many women’s historians (myself included) in the 1990s. But looking back, I wonder if it gained traction in part because it could seem less challenging to the status quo. I could imagine a contemporary parallel to scholarship related to “race” versus “white supremacy,” terms that may address similar issues but carry very different valences.

Some of this expansive use of “gender” undoubtedly reflects the introduction of the term as a powerful analytic category in the 1980s.7 Attention to gender undoubtedly also reflects (and helped to produce) a shift toward cultural histories of power relations, rather than social histories of women’s lives.8 Indeed, the frequency of the word “cultural” doubled between 1985-2005, while the word “social” saw a steady (though not as dramatic) downturn. It may also be that abstracters are relying more comfortably on “gender” as a catchall explanation of complex arguments about status and power that might have been classified with other terms a decade earlier.9 Word frequency statistics bear this out: words such as “patriarchy” and “sexism” show no significant increase over this time period, and “feminism” shows little increase after the 1980s.10 Perhaps this reflects less attention to terms that might be seen by mainstream readers as more strident versions of feminist history: “gender” has been naturalized to a generic identifier less associated with activism (witness the regular appearance of “gender” as a checkbox category on institutional forms), whereas “patriarchy” and “sexism” still carry the imprint of a particular activist movement.11

I would love to see a study of how women’s, gender, and sexuality histories are described in more recent abstracts. Anecdotally, it seems that more historical publications are requiring abstracts, so it would be enlightening to analyze author-produced abstracts to see how they might compare to database-produced ones.

Like the percentage of women’s history abstracts generally, the increasing use of the word, “gender,” also leveled off by the mid-1990s. We certainly hope that this does not mean that women’s and gender histories have already seen their heyday. A more positive interpretation may be that women’s history is becoming more integrated into diverse topics, so that the women’s history content is not fully explained or easily identified in brief abstracts. It may also be possible that as women’s history becomes mainstream history, abstractors see less need to mark such scholarship as focusing on women.

Figure 2:

Frequency of the Word ‘Gender’ in Abstracts from 1985-2005

As any historian who was around in the 1990s can attest, Joan Scott’s conceptualization of gender was incredibly influential, and that shift toward looking at power relationships, not just women’s lived experiences, is very clear in this figure. Joan W. Scott, “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis.” The American Historical Review 91, no. 5 (1986): 1053-075 doi:10.2307/1864376.

Paragraphs like this displays my own interests in the structure of the academy, not just its intellectual products. At the time I wrote this article, institutional efforts aimed at addressing the continued marginalization of various underrepresented minorities in academia were just ramping up. I continue to believe that any analysis of scholarship requires simultaneous attention to the structural conditions under which that scholarship is produced. For instance, if I wrote this paragraph now, when I’m much more aware of trans issues, I probably would not refer to women’s historians as “female” without qualification. My recent work on racism and sexism in a popular scholarly database extends this kind of analysis (Sharon Block, “Erasure, Misrepresentation, and Confusion: Shortcomings of JSTOR Topics on Women’s and Race Histories,” Digital Humanities Quarterly, 14:1 (2020) [http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/14/1/000448/000448.html

Still, this leveling off also raises several questions for women’s historians and the profession more generally. First, what is an appropriate ultimate level of women’s history publications within historical journals? Can we numerically quantify when women’s history has “succeeded” and is suitably represented in historical publications? Should attention to women appear in half of all historical studies? Should a certain percent of studies include a feminist or gendered analysis? Second are more profession-based questions: do publication levels fairly reflect the percentage of women’s historians? If not, are there material factors – likely related to women’s place in the profession -- that might account for any discrepancy? Women’s historians are, of course, not all women, but they are disproportionately likely to be female, and thus the field is more impacted by professional equity issues than many other thematic fields.12

The next two paragraphs are a basic word frequency analysis that is, to my mind, really powerful proof of the degree of marginalization of women’s history in historical publishing. Some might argue that the word “women” appearing more frequently than men shows the over-representation of women’s history, but it is clear that women’s appearance is notable in ways that men’s is not in historical scholarship. The analysis of gendered pronouns suggests that men are still the overwhelming focus of historical publications.

Moreover, the overall increase in work on women’s history does not translate into equitable treatment of women and men in historical studies. Women do receive more attention as a group or subject of study in overall abstracts. The word “women” is used almost six times as often as the word “men.” This likely reflects the scholarly interest in women as a category versus the appearance of individual men as incidental subjects of historical inquiry, without analytic attention to gender identity.

Footnote 3 notes that we undertook standard pre-processing, such as removing stopwords from the text we were analyzing. However, after a few topic modeling runs, we realized that many standard stopword lists include gendered pronouns as stopwords (for example, http://xpo6.com/list-of-english-stop-words/), which prevents and analysis of their presence as a proxy for the degree to which abstracts focused on men versus women. Keeping these pronouns in the processed text allowed us to confirm that men were still overwhelmingly the focus of publication abstracts.

But what about attention to individual male and female subjects? The comparative use of some objective and possessive personal pronouns, “her,” “hers,” “him,” and “his,” makes clear that individual men are still implicitly the focus of the majority of historical scholarship. Together, all of these pronouns are used over 200,000 times in the half million abstracts. Yet only 14% of these uses are for “her” or “hers.” While women, as a category, are a subject (perhaps even an over-essentialized subject) of analysis, historical scholarship still appears to be largely focusing on men’s activities as a matter of course – not necessarily to analyze men as gendered beings, but as default individuals of study.

At the time, masculinity studies seemed to be both on the rise and controversial; some feminist scholars felt that women still should be the focus of the field. Hence this paragraph confirming its rise and gently weighing in to reject the idea that scholarly focus has to be a zero sum game. While writing this article, I focused on presenting clear and convincing data findings. If I wrote the article now, I would foreground my opinions on the field more, and present more potentially controversial perspectives on the implications of the data findings. Of course, it is much easier to do this with a track record of digital history publications behind me, not to mention another decade of seniority in the profession.

Nevertheless, analytic studies of masculinity studies have unequivocally been on the rise.13 The appearance of the term “masculinity” shows a dramatic trajectory –from a virtually non-existent frequency of`1 in about every 90,000 words in 1985, to appearing more than once every 2000 words by the year 2000. This upswing reflects the ways that historical articles have begun to focus critically on men beyond their incidental appearance. This increase likely suggest a more widespread interest in fully understanding all aspects of gendered power dynamics. But does the increase in masculinity studies relate to the slowing expansion in women’s history in the new millennium? We should be careful not to posit a zero-sum-game of interest in gender-related studies, but it may be useful to consider the relationship between feminist, women-focused, and broadly-constituted gender histories.

Historians love regional differentiation. Because America: History and Life (AHL) focuses on North America and Historical Abstracts (HA) focuses (theoretically) on everywhere else, it made sense to compare the two databases. I was a little surprised that women’s history pretty consistently appeared more frequently in North American-focused publications.

Turning to a regional analysis of history abstracts shows that a higher percentage of articles are being published on women in North America than in the rest of the world. Almost twice as many North American abstracts as Non-North American abstracts include either “woman,” “women,” or “gender” somewhere in the entry (almost 10% v. about 5%, respectively). As Table 1 shows, a variety of words relating directly to women are almost twice as likely to appear in North American abstracts as non-North American abstracts.

I spent a lot of time thinking about how to present tables and charts in ways that would be most accessible for women’s historians. All of the charts are, I hope, pretty straight forward. Still, as a colleague emailed when this article was originally published, “it’s a good thing I know the author because otherwise those charts would scare me to death!!” A divide between quantitative and qualitative comfort probably continues to exist. In the past decade, however, scholars have become much more comfortable with visual representations of data, which are now more readily producible without particular software expertise. Perhaps non-numeric graphics would have reduced that knee-jerk math/data fear that some women’s historians felt when viewing the many tables and graphs in the article.

Table 1. Select Women-Related Word Frequencies in Overall Abstract

| Word | North America | Non-North America |

|---|---|---|

| Female(s) | 1 in 2625 words | 1 in 2786 words |

| Feminism(s) | 1 in 5505 words | 1 in 9619 words |

| Gender(s) | 1 in 1334 words | 1 in 2524 words |

| Her(s) | 1 in 795 words | 1 in 1513 words |

| Mother(s) | 1 in 3956 words | 1 in 7792 words |

| Wife | 1 in 6062 words | 1 in 11,346 words |

| Women | 1 in 261 words | 1 in 462 words |

For most of the trends I discussed, I aimed to break them down to see what changed over time. It was a tricky endeavor – and I did not always find the best balance – to providing accurate information and offering a readable narrative. This has been a challenge for me in various data mining and digital humanities settings: how to present quantitative findings, particularly of huge corpuses, in ways that make the findings a tool for analysis, not the end result. This piece sometimes erred on the findings over argument side.

These word choices mark the larger presence of women’s history abstracts within North American history overall. Women’s history abstracts are twice as big a proportion of North American abstracts (almost 9%) as non-North American abstracts (slightly more than 4%). This has been fairly consistent over time of publication: in 1985, women’s history-focused abstracts accounted for over 6% of all North American abstracts, but just over 2% of non-North American abstracts. In 2005, women’s history abstracts had expanded to almost 11% of North American abstracts and 6% of non-North-American abstracts. We can view these increases as positive or negative trends: on the negative side, North American women’s history was about the same proportion of it regional field in 1985 as non-North American women’s history was two decades later. On the positive side, the amount of women’s history on non-North American topics has tripled in two decades.

Footnote 14 offers details on our data analysis process as well as acknowledging our inability to include all regions in our analysis.

Table 2 compares the regional breakdown of overall abstracts and women’s history abstracts in more detail. North American abstracts account for just over 1/3 of overall abstracts, but more than half of abstracts on women’s history.14 In contrast, several non-North American geographic regions are particularly underrepresented in women’s history. Work on Eastern Europe/Soviet regions shows the biggest discrepancy, accounting for almost 17% of all abstracts, but less than 7% of women’s history abstracts. Western Europe and, to a lesser degree, South Asia, are both overrepresented in women’s history percentages in their fields.

Read now, this is a rather weak paragraph on the reasons for the lack of attention to historical topics outside of the West. Today, I would be more direct about racism, xenophobia, American exceptionalism, and the structure of the publishing industry. Still, I will give myself a little credit for trying to point to the ways that women’s history publications related to the treatment of women in academia.

Source availability, feminist activism, sexism, and acceptance of women’s history as a legitimate field of study all contribute to these regional variations. In the case of Eastern Europe, scholars have already suggested that such underrepresentation results from a significant “infrastructural vacuum and institutional resistance” to women’s history. This is, perhaps, the case in other regions as well. And the reverse may also be true – it would be worth investigating whether North American historians or journal editors are comparatively more supportive of women’s history.15

This was a hard chart to figure out how to format. I wanted to make clear that the “Regions outside of North America” was a breakdown of “Non-North America (HA).” In retrospect (and with better presentation design tools available a decade later) two side-by-side graphic representations may have worked better. Nevertheless, I really value the detail in this table that makes clear how North American and Western Europe topics overwhelmingly dominated both women’s history and general historical publications.

Table 2: Regional Distribution in Women’s History versus Overall Abstracts

| Region | Women’s History | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| North America (AHL) | 52.9% | 35.9% | |

| Non-North America (HA) | 47.1% | 64.1% | |

| Regions outside of North America | |||

| Africa | 5.9% | 5.4% | |

| East Asia | 7.3% | 8.0% | |

| Eastern Europe/Soviet | 6.7% | 16.9% | |

| Latin America | 6.4% | 7.6% | |

| Middle East | 3.1% | 4.4% | |

| South Asia | 3.4% | 2.2% | |

| Western Europe | 53.8% | 41.9% | |

| Other/Unknown | 13.4% | 13.5% |

When I researched and wrote this article, there seemed to be significant discussion and debate about whether women’s historians only wanted to do 20th-century scholarship, and how this was a major flaw in the field. Accordingly, I analyzed the chronological spread of women’s history. AHL and HA categorized the scholarship it abstracted by time period, so I could compare women’s history’s chronological foci to general historical publications' chronological foci.

We might think that the overrepresentation of North American scholarship on women’s history can be explained by chronology. If women’s history tends to be disproportionately concentrated on the most recent centuries, a country with a relatively abbreviated early history would be likely to have an increased proportion of articles related to women’s history. However, when we compare time periods addressed in women’s history abstracts and overall abstracts from c. 1450-20th century, it does not seem that women’s history is significantly more recently-focused than the profession as a whole.

This table offers a good example of the many expertise-based choices that are necessary for a thoughtful analysis. It would have been simpler to provide a chart where each row was a century. AHL and HA provided the years on which an article focused, but as in all data analysis, I had to make decisions about how to aggregate and present it meaningfully, such as how to group work that crossed decades (see footnote 16). For instance, scholarship repeatedly focused on the 1880s-1920s, which does not fit into a category of a single century. I also decided to break out the pre- and post-1945 time periods because they showed that the women’s history was more under-represented in the pre-1945 period. Each figure in this article represents extensive pre-analysis of the data, re-running and re-categorizing with the goal of best highlighting and coherently presenting the most important findings.

As Table 3 shows, the twentieth century accounts for the overwhelming majority of all historical abstracts from c. 1450-onward.16 However, women’s history abstracts are not disproportionately focused there– if anything women’s history is slightly underrepresented in twentieth-century scholarship. Work exclusively on the twentieth century accounted for about 57% of women’s-history-focused articles, and about 63% of overall articles. Still, this analysis supports Judith M. Bennett’s conclusion that women’s history and overall historical scholarship focus primarily on post-1800 time periods.17

Judith Bennett’s work had rightly impacted on how scholars understood the state of the field of women’s history. Adding to her contention that women’s history disproportionately studies modern time periods, we found that women’s history publications most focused on the nineteenth and turn-of-the-twentieth century.

Our larger analysis adds to Bennett’s by teasing out some of the differences between post-c. 1450 women’s history and scholarship more broadly. Rather than unrelentingly focusing on the very recent past, women’s history abstracts focus more on the nineteenth century than does overall scholarship–about 16% of women’s history abstracts but just 12% of general abstracts focus exclusively on the nineteenth century. Likewise, women’s history articles are more likely to focus on turn of the twentieth century period than does general scholarship (6.7% v. 3.7%), which focuses more broadly on the first half of the twentieth century.18

Here too, I could see a graphic representation working better to show the distribution of time periods in historical abstracts. I am not opposed to precise quantitative tables, but think that graphics generally allow for a more clear and immediate impression, especially for an audience who is not particularly quantitatively oriented. For Table 3, seeing the relative value may have been more important than knowing the size of a category to the 1/10th of a percentage point. At the time, I had hoped that other scholars would pick up on this research and further refine its findings, so decided that exact percentages would be more useful for those interested in pursuing further analysis.The asterisk below the table is another example of my efforts at transparency and clarity and footnotes 13, 16, and 22 offer further details on the classification process we used to analyze chronology.

Table 3: Distribution of Abstracts Over Various Time Periods

| Time Period | Women’s History | Overall |

|---|---|---|

| c. 1450 through 17th Century | 5.1% | 5.6% |

| 18th Century | 4.1% | 3.8% |

| 18th through 19th Centuries | 2.2% | 1.8% |

| 19th Century | 15.9% | 12.2% |

| Turn of the 20th Century (1880-1920) | 6.7% | 3.7% |

| 19th through 20th Centuries* | 5.0% | 4.2% |

| 20th Century (in total) | 57% | 63.1% |

| 20th c: 1900-1945 | 16.9% 21.1% | |

| 20th c: Post-1945 | 30.2% | 32.9% |

| 3 or more Centuries | 3.9% | 5.6% |

*Twentieth-century percentages include 1900-1999 dates, as well as 1900-1945, and post-1945 categories.

The finding that women’s histories undertook fewer chronologically sweeping narratives intrigued me. I suspect that this could be due to women’s historians facing decades of accusations of transhistoricism and critical accusations of wrongly undertaking “activist” history, as well as to the developmental stage of the field. It may also reflect the degree to which women’s historians have been accepted as intellectual authorities in the profession.

Bennett has also explicitly encouraged feminist scholars to avoid taking refuge within our historical era of expertise. However, women’s historians seem reluctant to write across time periods: overall scholarship was much more likely to focus on three or more centuries than was women’s history.19 It may be that women’s historians, already all-too-often battling the perception of “advocacy” or “ahistoric” scholarship, take great pains to stick closely to our historically-specific evidence. Yet we risk this making us timid about claiming expertise across wide swaths of time or place, and in so doing, we may be limiting the significance of our findings.

Paragraphs like this, that narrate expected chronological differences across regions, are not particularly exciting or surprising. But presenting basic data findings still strikes me as important to document. Today, I would add a discussion of how the start of North American abstracts in the c.1450 time period reflects a problematic settler colonial approach, not a chronological reality. (See for instance, Juliana Barr, “There’s no such thing as ‘Prehistory’: What the Longue Durée of Caddo and Pueblo History Tells Us about Colonial America,” The William and Mary Quarterly 74, no. 2 (April 2017): 203–40.

As we might expect, non-North American general abstracts are much more likely to focus on earlier time periods than are North American abstracts. Less than 4% of North American abstracts focus on the c.1450-1799 time period, compared to 12% of non-North American abstracts. In addition, non North-American women’s history is actually more likely to focus on earlier time periods than general scholarship: more than 15% of non-North American women’s history abstracts focus exclusively on c.1450-1799. Correspondingly, non-North American women’s history actually focused less on the 20th-century than did overall non-North American abstracts (51% v. 69%).

My writing tends to signpost, such as in this conclusion to a sub-section. In a historical journal piece that involves quantitative data with which some readers might have not fully engaged, I particularly wanted to narratively flag the section’s findings.

The limits of AHL and HA databases restrict us from including ancient and medieval history in this analysis. However, within these limitations, women’s history is not disproportionately more recently-focused than history as a whole. Rather than women’s historians abandoning earlier time periods, non-North American women’s history appears to have focused more on c.1450-1800 topics than has the field at large. Still, because women’s history is a bigger percentage of North American history – which is the biggest overall field -- these chronologically earlier studies may not seem to hold as noticeable a place in women’s history publications.

This section identifies and looks at the content of the publication abstracts that included notable content on women’s history. I envisioned the article going from broad (all of historical abstracts) narrowing to a smaller subset of women’s history, and then ending with an even narrower in-depth analysis of one sub-theme within women’s history. I thought this would show potential uses of data mining from varied vantage points.

Focusing on the topics that account for women’s history within all historical abstracts confirms that women’s history publications make up a larger part of North American history abstracts then those focused on the rest of the world. Our topic model run of the half million abstracts identified seven major subject areas focused primarily on women and gender (Table 4). Within every area, women’s history made up a bigger part of North American-focused scholarship. Thus, part of the reason that U.S. women’s history can seem to dominate overall women’s history overall is due to women’s history’s bigger place within North American history than within other regions.

One of the confusing aspects of topic modeling is that it analyzes topics within the content overall. So a single abstract could be assigned numerous topics. Some readers did not understand how 3% of abstract content could be women’s history, while 6% of the number of abstracts included a focus on women’s history. I tried to explain this in detail here but recognize that how topic modeling works was not intuitive for many readers. Footnote 20 specifies the different numbers of topics (40, 80, 120) we tried out in topic modeling runs of this corpus; we tried to be as transparent as possible about the our technical choices without bogging down the text with those details.

Women’s history-focused topics account for almost 3% of the content of all historical abstracts.20 Because topic modeling identifies the content overall, rather than counting each abstract that mentions a women’s history topic as being exclusively about women’s history, this c. 3% represents the content of all scholarship that focuses on women’s history to the exclusion of other topics. In other words, topic modeling can separate out the parts of women’s history abstracts that simultaneously address other scholarly subjects (e.g.: politics, religion, labor) to focus exclusively on the women’s history language. Thus, 6% of all abstracts may have significant women’s history content, but only about 3% of the text of all abstracts focus explicitly on women’s history – concretely showing the full integration of women’s history with other thematic areas of study.

Looking back, these women’s history topics look rather staid. I don’t know if that was a result of the work being done, how it was abstracted, or how I, as domain expert, interpreted the topic model results. I could imagine that in 2021, I might focus on different topic words in labeling each topic because our collective jargon has changed over time.

Table 4 explores these thematic areas of women’s history within historical scholarship. Work on feminism and suffrage is one of the largest topical categories, followed closely by scholarship on more intimate details of women’s lives: families and kinship, and marriage and sexuality. Literary subjects – whether biographies of notable women or literary approaches to women’s history – are also well represented. How are we to evaluate this broad variation of fields that make up women’s history scholarship? Should there be more scholarship overtly on feminism or less on personal lives – however we might define those two categories? Rather than presuming to dictate what women’s history should consist of, we note that even at this high level vantage point, there is a significant spread of topics across multiple aspects of women’s lives. We also note that abstracts likely focus more on methodologies and source than full text, which may account for the prominent percentage of literature and biography-related content.

I wanted to make sure that the arguments made from the data mining results did not get lost in the quantitative details, so offer a narrative summary here.

I debated how much to explain about the probabilistic topic modeling process, about labeling of topics, etc. Here I decided to just include the topic labels I added to topic modeling topics as a domain expert, rather than including lists of most frequent terms in each topic. If I wrote this now, I might redo this table into a visual to make the regional differences in thematic foci more easily scannable.

Table 4: Major Women’s History Topics in Overall Abstracts

| Topic | North America | Non-North America |

|---|---|---|

| Women & Biography | 0.53% | 0.22% |

| Family, Kinship | 0.58% | 0.42% |

| Feminism, Suffrage | 0.71% | 0.36% |

| Women’s Labor & Work | 0.48% | 0.29% |

| Women & Literature | 0.62% | 0.16% |

| Marraige, Sexuality | 0.55% | 0.43% |

| Sex Roles | 0.37% | 0.22% |

| Total | 3.8% | 2.1% |

There is no doubt that women’s history accounts for a diverse and growing proportion of historical scholarship. Within this growth, however, its rate of increase has been slowing. An increased focus on “gender” in abstracts partly represents changed scholarly interests, but likely also reflects a changed shorthand for women’s history. Even though references to women, as a group, far outnumber mention of men as a category for analysis, the overwhelming majority of abstracts still talk about individual men, not women, as historical subjects. Regionally, by multiple measures, women’s history holds a significantly larger place in the North American and Western European historical fields than in many other regions. However, women’s history’s seemingly-disproportionate focus on more recent time periods appears to be a reflection of the historical profession as a whole. In the next section, we focus more in depth on women’s history abstracts to further analyze the extent to which these trends relate to women’s history rather than larger trends within the profession.

The Field of Women’s History

One of the values of comparing all historical abstracts to women’s history abstracts is the ability to pinpoint where variations occur – if women’s history publications follow or depart from more general trends in historical publishing.

Here we explore the 30,891 abstracts that focused significantly on women’s history, exploring how the picture changes when we look within women’s history abstracts, rather than at women’s history as part of the historical field as a whole. We show that women’s historians speak with a regionally-shared language, and that some regional variations in content relate more to the place of women’s history within various subfields than the content of women’s history scholarship. We continue to dissect the notion that women’s history has developed a twentieth-century bias and suggest that it is more complicated than a simple shift toward scholarly emphasis on the most recent time periods. In terms of absolute numbers, women’s history has not turned away from c.1450-1799 time periods; rather work on the post-1800 period has increased, therefore changing the overall chronological balance.

This paragraph and associated table offer an opportunity to directly compare overall abstracts to women’s history abstracts. The larger focus on women-related terms in North American-focused histories largely disappears within women’s history abstracts.

Table 1 showed that women-related words appeared far more frequently in North American abstracts than in abstracts on the rest of the world. This regional difference largely disappears within the 30,891 women’s history abstracts (Table 5), suggesting a trans-regionally shared language with which experts talk about women’s history. Thus, the broad regional differences in overall word frequencies appear to have more to do with the place of women’s history in different regions and less to do with the amount of work being done within women’s history. Still, some of this lack of variation is likely due to the flattening of complex issues into abstract-friendly terms, and it does not mean that abstracts that focus on women’s history in different regions and time periods take identical approaches to the field.

The structure of these databases suggests the disproportionate focus on the United States (and Canada), and I noted this structural overemphasis in the following paragraphs. I would hope that the most recent decade of women’s history publications would show less dominance of North American (and secondarily Western European) regional foci.

Within women’s history abstracts, we can see an array of regional transformations between 1985 and 2005. In the mid-1980s, women’s history was significantly dominated by North American scholarship, which made up close to 60% of all abstracts. But by the mid-1990s and continuing through the first years of the new millennium, women’s history had become equally focused on regions outside of North America.21 Of course, equality between one continent, made of two nations, and the rest of the world is not exactly parity, but it does suggest the expansion of women’s history beyond its earlier regional foci.

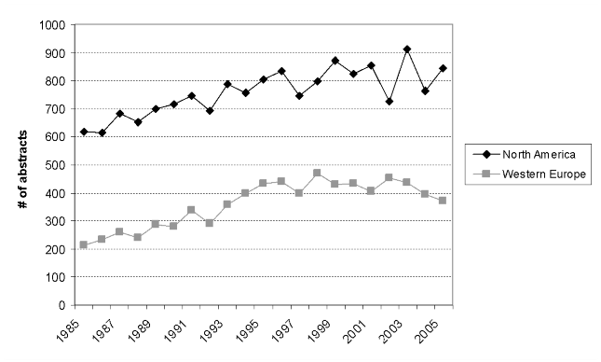

Anyone who has undertaken quantitative analysis knows how important it is to think carefully about what the data shows. At first glance, Figure 3 looked like 2 parallel lines increasing, but the rate of increase was nearly double for Western Europe as for North American women’s history abstracts. I extensively analzed each figure that made it into the article (and many more that didn’t) to be sure all findings were both accurate and significant.

Western Europe was overwhelmingly the largest non-U.S. regional focus of women’s history abstracts (Figure 3). While both areas' article abstracts increased their absolute numbers fairly steadily over the twenty year period (with some leveling in the new millennium), this was a much bigger proportional increase for Western Europe – it increased about 100% over its starting numbers, compared to only about a 50% increase for North America. So while women’s historians may be turning to non-Western regions, the attention to Western history is still continuing to increase substantially.

If the article were structured differently, I might have had a section analyzing the many areas of change that seemed to level off after the early-to-mid 1990s. I bring it up repeatedly throughout the article, but it could be an interesting focused analysis to think about broad changes in the field of historical publishing.

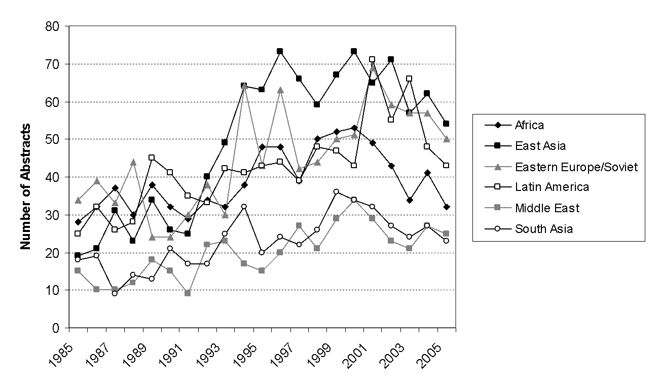

Outside of Western Europe and North America, each regional field’s women’s history abstracts likewise increased over time (Figure 4). One of the most dramatic increases occurred in East Asian history: in 1985, it was barely the fourth highest number of abstracts; by the mid-1990s, it had more than doubled to have the highest number of abstracts of any regional field of women’s history outside of North America and Western Europe. Most regions seem to be declining in the first half decade of the twenty-first century, with African women’s history abstracts showing the largest drop. Overall, scholarship still increased in each of these regions, showing the most pronounced gains occurring in the first half of the 1990s and then leveling after 2000.

I thought about using percentages to convey these frequencies because readers may be more used to seeing percentages, but I wanted this table directly comparable to Table 1, and Table 1’s percentages would have been as small as 0.009% which did not seem particularly reader-friendly.

Table 5: Select Word Frequencies in Women’s History Abstracts

| Word | North America | Non-North America |

|---|---|---|

| Female(s) | 1 in 295 | 1 in 227 |

| Feminism(s) | 1 in 618 | 1 in 604 |

| Gender(s) | 1 in 156 | 1 in 150 |

| Her(s) | 1 in 135 | 1 in 171 |

| Mother(s) | 1 in 750 | 1 in 818 |

| Wife | 1 in 1743 | 1 in 1759 |

| Women | 1 in 26 | 1 in 25 |

I thought about smoothing the data on this chart to make the trend lines more visible, but ultimately decided to present the data in its original form. Perhaps now, with better graphics tools, I would draw dashed trend lines through the data.

Figure 3:

Regional Variation in Women’s History Abstracts, 1985-2005 (Part I)

While the question of which time periods of women’s history received adequate attention may no longer animate the field, at the time I wrote the article it was a significant concern. Employing a topic modeling analysis of a giant corpus seemed like an ideal application to test hypotheses about women’s history publication trends.

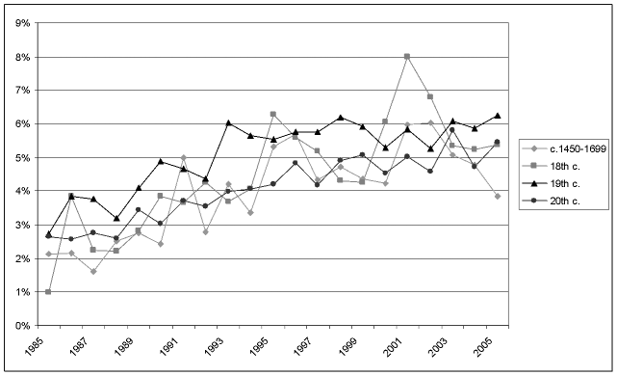

The chronological breakdown of women’s history has recently received a great deal of analytic attention. While abstracts on all time periods of women’s history have increased along broadly similar trajectories since 1985 (See Figure 5), the most marked increase has been in nineteenth – not twentieth-century -- women’s history.22 In fact, the numbers of twentieth-century women’s history abstracts actually increased the least of any time period between 1985 and 2005. Twentieth-century women’s history abstracts grew to 1.4 times their 1985 number, while c.1450-1699 century abstracts grew to 1.7 times; eighteenth-century grew to 1.9 times and nineteenth century grew to 2.1 times their 1985 numbers by 2005. Alternatively, looked at as a percentage of women’s history abstracts each year, twentieth-century women’s history has actually declined – from 75% of all women’s history abstracts in 1985, to 68% in 2005.

I struggled to present these six trend lines in a legible format. Color would have been easier, of course. I decided on two charts of regional variation (Part I and Part II) because including Western Europe and North America with all other regions would have left those other regions illegibly squished together due to their substantially lower numbers (ranges of c. 10-70 v. c. 200-900).

Figure 4:

Regional Variation in Women’s History Abstracts, 1985-2005 (Part II)

I was surprised to find that twentieth-century women’s historical publication was not disproportionally crowding out other women’s history; a comparison to historical publishing overall presents a more complex picture of chronological spread. This is yet another reminder that finding and reporting data is usually a multi-step process of investigating various permutations, looking for supporting explanations in related data sets, and above all, being careful to interrogate and cross-check all findings.

Thus, twentieth-century women’s history publications have not been increasingly dominating the scholarship on post-1450 women’s history. But there are several reasons why women’s history may still appear to be disproportionately focused on twentieth-century history. First, abstracts on twentieth-century history overall far outnumber all other time periods put together, meaning far more absolute numbers of women’s history publications on the twentieth century. Second, overall abstracts that are identifiably on the twentieth century have declined fairly significantly since 1985 – from a range of 16,000 abstracts/year for 20th-century scholarship in the late 1980s to a low of below 12,000 by the twenty-first century. In contrast, all other time periods have held steady or declined only slightly. Thus, even though women’s history on the nineteenth century has increased the most, women’s history has become a much larger percentage of overall twentieth century scholarship than of other time periods.

I have occasionally thought that I could have turned the discussion of chronology into its own article, with more in-depth analysis, examples of scholarship, and narrative explorations. An article with a clear and linear argument that used data mining to make a single point may have been more appealing to many women’s historians. But I had an interest in showing the range of results from large scale data mining as a proof of concept kind of approach, in the hopes that others would build on this kind of methodological work.

Here, too, I might have chosen to smooth the data somewhat, or perhaps present this with better graphics. Looking back, I’m not sure how crucial this figure is other than to show roughly similar trends. I wonder if the larger variations in 18th-century scholarship relates to its smaller overall numbers of abstracts; at the time, I tried to look for an explanation of the big spike in 2002, but could not find a simple explanation.

Figure 5:

Percent of Women’s History Abstracts withn Time period by Publication Date

This means that even though the twentieth century remains the largest focus of history as a whole, it does not appear that women’s history has any more disproportionately focused on that time period; the increases in 20th-century women’s history have not outpaced the increases in other time periods. Indeed, considering the limitations that face historians of periods predating the twentieth century, women’s and gender historians have become increasingly creative in finding and mining primary sources related to women throughout history.

This section emphasizes the topical power of topic modeling. Again, we tried to be transparent, so footnote 23 notes how we combined some topics in a 40-topic topic model.

Thus far, we have focused on the amount, not the content, of women’s history abstracts. Table 6 identifies, through topic modeling, the broad subject areas of study within women’s history.23 In contrast to the broad areas of women’s history identified within the larger historical canon (Table 4), the subjects within women’s history clearly cover many specific thematic fields. The largest topical area focuses, as does much general historical work, on various regional and national specificities. Other topics range from social to political to cultural to intellectual histories. As Gerda Lerner noted in her study of U.S. history scholarship, work on literary subjects (such as much of the Literature and Biography topics) remains a substantial segment of women’s history publications.24

Because readers repeatedly seemed perplexed over how topic models identify topics, we reiterated what we are measuring with these topics, complete with examples, here.

It is also worth remembering that the topic model creates multiple categories per abstract, so these topics measure the percentage of overall content of the abstracts, not individual topics per abstract. For instance, an abstract on labor and family in Latin America would count toward each of those three subject/regional areas in proportion to the number of words in that abstract that were statistically assigned to each of these topics. Thus, rather than marking each abstract with an exclusionary set of labels, each abstract contributes to a variety of topical areas in proportion to the amount that that abstract focuses on each area. This can produce more realistic subject categorizations and challenge the sometimes-mainstream image of women’s history as not intrinsic to other subfields.

Table 6: Broad Topic Areas in Women’s History Abstracts

| Topic Area | % of text aaddressing |

|---|---|

| Regional Focus (inc. colonialism/nationalism) | 12.7% |

| Labor, Economics, Class | 11.7% |

| Literature, Biography | 11.0% |

| Sexuality, Reproduction | 9.0% |

| Historiography, Reviews | 6.4% |

| Gender & Identity | 6.2% |

| Politics, Politcal Movement | 5.4% |

| Family, Marriage | 5.1% |

| Race, Slavery, Civil Rights | 4.3% |

| Suffrage, Feminism | 3.6% |

| Religion | 3.4% |

| Arts, Media | 3.3% |

| War | 3.3% |

| Education | 2.6% |

| Welfare | 2.5% |

| Other | 9.7% |

I wanted to emphasize the regional differences in topics. The differing terminologies used within regional women’s history abstracts struck me as an interesting insight into the broad trends within each region’s version of women’s history. At the same time, I’m now struck by how little race appears in this article; given how focused “race” topics were on North American history abstracts. I recall not wanting to be overly U.S.-focused, so may have underplayed the topic, since it was not an easily comparable one. I would hope that in 2021, the scholarship would support and even require a more intersectional analysis.

There are some broad regional variations in these topics: Not surprisingly, non-North American abstracts are more likely to focus on regional issues than are North American abstracts, while Race, Slavery and Civil Rights appear three times as often in relation to North American abstracts. More specific regional differences suggest an array of areas for future analysis. African women’s history focuses less on marriage and family than other regions, but words such as “power” “status” and “traditional” occur comparatively frequently. Commentary on religion was most common in Middle East women’s history (about 19% of the focus of its abstracts, compared to less than 6% for any other region). Middle East history also focused strongly on the study of feminism. East Asian history was most likely to focus on marriage and families. Latin American women’s histories focused more than most regions on political movements, as well as labor and marriage. Eastern Europe/Soviet abstracts were one of the most likely to reference “tradition” and focus on inheritance and households. South Asia scholars frequently addressed feminism and political movements, and were also the most likely to use the word “cultural”-- perhaps partly because of the importance of literary and post-colonial scholars doing South Asian women’s history. Work in North American history was one of the least likely to focus on marriage and family, and among the most likely to focus on sexuality, race, labor, and the term “public.” Finally, Western Europe focused far more on families, households and status than did North America.

This paragraph is a pretty week analysis of some really interesting trends described in the previous paragraph. This is the trade-off of a data survey piece: it is difficult to do a deep dive into any one set of findings. There were moments when I thought this article could be a short book – one chapter on each area of findings and analysis. But my own approach to scholarship favors jam-packed research and condensed writing. I also, honestly, did not think I wanted to invest so much into topic modeling – I wanted to continue research and publishing in colonial North American history. Ironically, my subsequent monograph involved hand-coding c. 4000 documents, but scholars repeatedly categorized it wrongly as a computerized data mining project.

Even though, as Table 5 showed, women’s history abstracts use similar levels of women-focused language, this more complicated analysis of what women’s historians address suggests that different thematic emphases predominate in various regional specialties within women’s history. There are undoubtedly numerous reasons for these variations (e.g., source availability, disciplinary guidance), but it does seem that women’s historians are responding to their regions' particular historiographic concerns.

I thought it was interesting to compare the largest four categories of topics, making up about one-third of all topics, in very recent (post-1945) versus the most distant (pre-1800) time periods. I do wonder if abstracters on early time periods are likely to write more generally about subject matter than those who are trying to distinguish the array of scholarship on recent history. This is a question that a full text analysis of scholarship could help answer: what shared disciplinary terms do women’s historians use for scholarship across versus within specific time periods?

In terms of chronologic comparisons, generalizable topics of study best traversed chronologic distance. Tables 7 and 8 compare the largest individual categories in distant and recent time periods. Chronologically distant women’s history abstracts seemed to focus on more transhistoric topics, such as family and households, women, gender, or religion. In contrast, three of the four biggest topics in post-1945 abstracts focus on issues particularly pertinent to twentieth-century life, such as women’s relation to political parties, civil rights, or employment discrimination. Ironically, the specificity allowed by twentieth-century sources may encourage more parochial topics; distantly-focused women’s historians may be more likely to focus on topic areas that could be of broad scholarly applicability.25

Looking back, this is a bit of a cheat paragraph. I begin to summarize the previous section’s findings, and then turn to an array of (unanswered) questions to raise issues about those findings. I’m guessing I was tired and/or hitting my word limit by this point in the essay, to be honest. Still, these are reasonable questions that get at issues of systemic bias, structural impediments, and continue to connect the scholarship we do to the lived experiences of being a woman’s historian.

To summarize, the field of women’s history continues to expand in multiple directions. Even though all regional areas of women’s history have increased since 1985, U.S. and Western Europe still dominate the field. How do we begin to explain the complex factors that may have accounted for regional variations in amount and subject of study? To what degree are they about reception to these fields by women’s historians; reception within these regional fields to women’s historians, or artifacts of particular tipping-point moments in training or individual scholarship? While an array of recent reflections on the state of women’s history has endorsed the need for the continued internationalization of women’s history, scholars might want to first more fully explore the limiting factors that produce these variant trends.

More signposting to reiterate what we had just showed. If I wrote this now, I hope I’d be more adventurous and perhaps offer resolutions, specific areas for needed followup, etc. Again, this shows the tension between presenting a data-mined overview of the state of the field of women’s history and diving deeply into those findings.

Because the relative amount of women’s history content published on various time periods had been such a concern in the field, I wanted to offer a broad comparison of topical content of the two most chronologically far apart time periods. I called these subject areas “categories” rather than “topics” to signal that I had combined multiple topic model topics to create each category title.

| Table 7: Top Four Categories for post-1945 Women’s History Abstracts | |

|---|---|

| 11.5% | Economic Employment Disparities |

| 8.3% | Gender and Identity |

| 7.0% | Political Parties |

| 5.1% | Civil Rights and Affirmative Action |

| Table 8: Top Four Categories for c.1450-1799 Women’s History Abstracts | |

|---|---|

| 10.5% | Family and Households |

| 9.2% | Women and Men |

| 6.9% | Gender and Identity |

| 6.5% | Religion |

In terms of the time periods covered by the AHL and HA databases, the picture is a complicated one: women’s history focuses on more recent time periods, but no more so than the field as a whole. Indeed, by several measures, twentieth-century women’s history scholarship appears to have increased less than some earlier time periods. But the domination of overall twentieth-century scholarship can still leave women’s history looking like a very recently-focused enterprise. Finally, a subject area analysis of women’s history shows coverage of a diverse range of historical subjects, with differing emphases along lines of regional historiographic concerns. Despite these variations, broad topic areas of c.1450-1800 scholarship could easily provide productive intellectual connections to other chronologic times and places, and we hope scholars will increasingly consider chronologically and regionally broad thinking when doing women’s history.

Within Women’s History: Case Study of Sexuality

Here I wanted to show the ways that topic modeling could zero in on a particular subfield. I chose history of sexuality because it was an area I knew well.

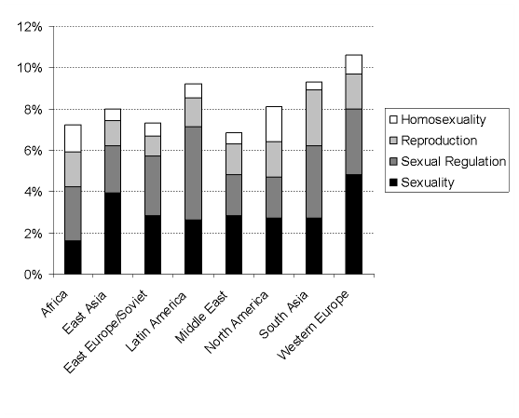

Historical studies of sexuality have developed, in part, out of work on women and gender, and remain firmly related to the field.26 Here we take sexuality as a case study to further explore the trends and patterns revealed by topic modeling. We break down the broad subject areas of sexuality histories, examine the degree to which studies in sexuality topics vary across time periods and regions, and ask how the topics within sexuality vary along these two axes. We suggest that both the amount and content of sexuality histories appear to vary more by region than by chronology.

Here, too, I thought it important to compare findings with larger sets of women’s history abstracts, to see the extent to which these matched or departed from more general trends.

Like most women-related subjects, sexuality appeared to be discussed substantially more in North American than in Non-North American abstracts overall. Of more than a dozen explicitly sex-related terms, only “prostitution” appeared more frequently in overall non-North American abstracts– and then, only slightly more often.27 More informal (and less supposedly-scientific) terms on homosexuality show some of the biggest regional differences: “Lesbian” and “gay” occur three-to-five times more often in North American as non-North American overall abstracts.

This section paralleled the explorations in the previous sections, beginning with word frequency analysis and moving onto topic modeling. Even though word frequencies are a basic computational methodology, I found them useful for comparing content, in this case, across regional abstracts.