Close Readings of Big Data:

Triangulating Patterns of Textual Reappearance and Attribution in the Caledonian Mercury, 1820-1840

Citation for Original Article:

This article began as a discussion of how we might utilise digital humanities techniques to identify scissors-and-paste journalism within the British newspaper press.1 While presenting my preliminary results as part of a wider symposium on reprinting, republication and copyright, questions were raised about publisher intent, namely the degree to which we could accurately distinguish between reprinting, a formal and usually legitimised process, and plagiarism, or unauthorised printing, merely by identifying multiple instances of a text within a digitised corpus. As a result, that which I had previously referred to as “reprinting” is styled here as “textual reappearance” so as not to imply publisher intent or agreement where it is not known. This discussion, I feel, is illustrative of the generally conservative nature of digital humanities research in periodical studies; there is both a strong aversion and significant resistance to inferring patterns statistically rather than from explicit testimony or deductive evidence of individual intent. These critiques encouraged me to develop ways of leveraging the statistical benefits of digital methodologies within a framework of traditional close-reading techniques.

Newspaper digitisation has been hailed as a revolutionary change in how the researchers can engage with the periodical press.2 From immediate global access, to keyword searching, to large-scale text and image analysis, the ever-growing availability of electronic facsimiles, metadata, and machine-readable transcriptions has encouraged scholars to pursue large-scale analyses rather than rely on samplings and soundings from an unwieldy and fragmentary record—to go beyond the case study and attempt the “comprehensive history” of the press that seemed so elusive forty years ago.3 Yet, after a decade of access to digital newspaper corpora, much of what has been attempted remains fundamentally conservative in approach.4

In surveying other uses of digitised newspapers collections over the past ten years, I found that periodical scholars tended to engage with collections in fundamentally traditional ways–browsing, establishing provenance and creating effective samples—but that the traditional practices for interrogating the archive were not seamlessly transferable to the digital archive; while researchers were generally responding to long-standing practical hurdles, such as travel and physical access to collections and time constraints upon research activities, effectively utilising digitised archives to address long-standing research questions still required novel ways of thinking about periodical material. My argument for pursuing this project was that if engagement with digital archives required a fundamental shift in practices, and therefore a significant outlay of effort in translating traditional research frameworks into a new environment, we might profitably divert at least some of this energy into asking fundamentally new questions.

In British Settler Emigration in Print (2016), Jude Piesse laudably provides URLs to the precise facsimiles she consulted and comments on the search parameters used to obtain her sample. However, her coverage was fragmentary, relying heavily upon select case studies rather than demonstrating general trends, admitting that "[d]igital searches frequently generate thousands of hits, which can be difficult to navigate or to appraise in any detail."5 She also subtly laments the loss of the immersive offline experience: “Despite the obvious benefits of focused digital searching, it is quite possible that it misses details that research in paper archives would bring to light”, the ease of jumping straight to a keyword discouraging a deep contextual understanding of the materials. Online interfaces encourage this type of sampling, with simplified full-text and metadata searches returning a list of “relevant” hits based on often-hidden algorithms, constricting research in ways similar to using a publisher-created newspaper index.6 Yet, from the beginning, researchers pushed at the boundaries of these offerings. Through a series of thoughtful search enquires, Dallas Liddle subverted these interface prompts and wrangled a sample of the metadata hidden within the Times Digital Archive.7 Bob Nicholson likewise went to admirable lengths to delineate the work required to effectively sample an externally curated digitised corpus.8 All of these uses stretched our understanding of the press beyond what was possible a generation ago but a much greater degree of abstraction, or large-scale analysis, is possible. Digitisation offers an opportunity to understand the newspaper press as a multipolar, interactive system—as something other than the sum of its parts.

During my PhD and early postdoctoral research, I came upon the idea of scissors-and-paste journalism in a manner that, it turned out, was common to most scholars engaged in significant newspaper research—noticing either a high number of attributions to other newspapers or coming upon the same article in different newspapers. While this practice was often considered amusing or curious by those I spoke to, only a small number of researchers had attempted to study it directly and they had faced similar difficulties. Relying upon serendipitous identification of reprints was impractical and early attempts to leverage digitised newspaper collections—usually beginning with a serendipitous identification followed by intense keyword searching—were time consuming and always in danger of misinterpretations and false narratives owing to missing waypoints on disseminations paths. Using computational techniques to find seed articles (wherever they might be) seemed a significant step forward but obtaining the raw data and computational power necessary for this sort of research as a junior humanities scholar was daunting as was the concern that any results obtained would be deemed insufficiently grounded in traditional research practices—a fad rather than a shift.

Although digitisation has impacted many aspects of periodical research, it is perhaps best placed to address the problem of textual reappearance and to understand its role within and between individual publications. Referred to as scissors-and-paste journalism, reprinting, syndication or simply duplication depending on the nature of the reappearance, the inclusion of a single, recognisable length of text in multiple publications was very common in the nineteenth century.9 Yet, despite the reappearance of text being oft-observed, much of our evidence for the underlying practices that prompted it is anecdotal: infrequent and sometimes erroneous attributions, memoirs of editors who engaged in the process, and recriminations by victims of the so-called pirate press.10 The precise scale of the process was largely unknowable before the advent of mass digitisation, as the fallibility of human memory and reading speed prevented a comprehensive view. The modern computer, in contrast, is well-suited to finding these identical blocks of text; rather than be distracted by nuanced interpretation, it needs only to stoically read through billions of lines of meaningless text in the pursuit of a matching pair. Indeed, the more removed the researcher is from the process the more effective the search will be. Using a graphical search interface to obtain a representative sample of even a single text has been proven cumbersome and imprecise.11 Instead, large-scale interrogations of multiple digital corpora have been required to effectively map wider trends.12 Yet, just as the serendipity of sampling constrains the wider applicability of a case study, the noise associated with big-data analysis makes applying wider textual trends to specific compositional practices problematic. Duplicates, out of context, tell us little of historical patterns of practice.

The term “middle-scale analysis” was derived from a conversation with several other digital humanities scholars long after the methodology had been first attempted. We had been discussing the relative merits of small-scale and large-scale analysis techniques for answering different research questions and we were considering the possibility of applying one set of techniques to a dataset of the other size. Thus, middle-scale does not refer to a third set of techniques or a medium-sized dataset, but rather finding a middle-ground between different approaches and sample sizes by moving back and forth between the two in iterative steps. The rest of this paragraph establishes the small-scale dataset upon which I will use techniques developed for large-scale statistical analysis.

The choice of the “Edinburgh-Arrow” issues for this case study was almost arbitrary. In order to properly ground the study, I chose a newspaper with which I had worked in the past, which I understood well and which I knew frequently engaged in reprinting reports from other periodicals. After comparing this title to the wider corpus with the plagiarism detection software Copyfind, I chose an issue that appeared to have an average number of reprints. When undertaking a close reading of that issue, I found a mention of the annual archery contest and, as the newspaper was published on different dates each year, I thought the contest would serve as a useful anchor for obtaining like-for-like issues across multiple decades.

In response to these difficulties, this essay explores a middle-scale analysis, one which iterates between the case study and big data to demonstrate how to best leverage digitisation when contextualising both small- and large-scale analyses. It explores the case of the Caledonian Mercury—a four-page, thrice-weekly newspaper published in Edinburgh by Thomas Allan—over the course of twenty years, 1820-1840, the heart of what Robert Cowan deemed “the first expansion” of the Scottish newspaper, after the post-Napoleonic boom in provincial titles but before the removal of stamp and advertising duties.13 It first compares a distant reading of the Caledonian Mercury against two of its London contemporaries, The Morning Chronicle and The Examiner, to provide a broad view of how its composition contrasted or aligned with newspapers known to be important sources (Chronicle) or curators (Examiner) of news content.14 It then provides a close reading of five “Edinburgh Arrow” issues of the Mercury in order to test and contextualise the trends seen in the distant reading.15 Finally, it offers an additional computational analysis that compares these five issues of the Mercury to contemporary issues of other newspapers to determine the proportionality of automatically and manually matched content. Through this iterative process, from large to small and returning to large-scale analysis, it demonstrates a digital means for understanding the degree to which the provincial press republished material from other newspapers and made use of implicit and explicit attributions.

One of the most important revelations of my postdoctoral work was the value of abstraction. While I had been trained to be highly detailed in my recording of historical events, and to zealously avoid overgeneralization, my understanding of theory and model making had been woefully underdeveloped. Attempts to expand my research capabilities through statistical work had been limited by deep-seated biases towards testimony-based deduction over statistical inference. Prior to my own work with reprint detection, my understanding of statistical text analysis was limited to topic modelling and I had had significant concerns about the conclusions those studies presented. They seemed to discount the biasing effects of their practical choices, such as return limits and corpus construction, which had been at the forefront of my mind during postgraduate study. Although these limits were likewise necessary for my own computational study, I tried to ground them in contextual awareness of the size and standard deviation of newspaper articles in this period and the speed and efficiency of postal routes and compositing practices. Upon reflection, however, I did not make the rationale for these choices explicit and thus opened myself to the same criticism I directed at those earlier statistical studies.

A Distant Reading of Three Newspapers

Unlike close reading, in which a text is read within its original structure, distant reading “aims to generate an abstract view by shifting from observing textual content to visualizing global features of a single or of multiple text(s)."16 Through this abstraction, the researcher is at least partially freed from pre-existing biases of focus, aiding them in the discovery of unexpected trends and correlations. Nonetheless, all computational analyses are guided by human-designed parameters that in some way bias the results, if only by limiting those aspects that are to be compared. Here, limits were placed on the category of materials analysed—by genre and corpora—and the unit of analysis—by word count and the temporal distance between units. These limits focused the results on instances of news content—which was quickly disseminated in word-for-word copies—without biasing for or against a specific tone or topic.

Because I had heavily criticised other statistical textual analysis for a limited problematising of their corpus’s construction, I attempted to provide at least a basic acknowledgement of the flaws and limits of my own corpus. Although I suggest a new opportunity presented by the particular shape of the British Library’s collection to explore non-geographical connections, this was a retroactive reflection and did not prompt or recommend the collection to me at the start of the project. However, I included it here to demonstrate that through the explicit acknowledgement of the limits and difficulties of the corpus, a researcher can open themselves up to different research questions and opportunities. Ignoring limits, or trying to dismiss them (as I did somewhat as well), will tend to limit the range or research discoveries rather than expand them. Were I to undertake this study anew, I would have made it more explicit what questions I could not answer and would have to abandon within the current project.

In terms of genre and corpora, a desire to focus on news content in the early nineteenth century, alongside practical licencing considerations, led to the use of the British Library 19th Century Newspapers, Part I and Times Digital Archive.17 Although far from a complete record of British reportage, access to these machine-readable collections allows a mapping of textual reappearance within newspapers on a previously unachievable scale. Combined, they contain seventeen individual titles for 1820, rising to twenty-seven titles by 1840, distributed regionally and across the political spectrum. Unfortunately, only two other Scottish periodicals are included in this collection, the Glasgow Herald and the Aberdeen Journal, which may have impacted the number of matches for regional news, discussed in more detail below. Nonetheless, initial analysis of the corpus demonstrated several non-geographically determined clusters of titles with significantly overlapping text, suggesting multiple national networks of news dissemination against which to test initial hypotheses.

The software I used for computationally identifying reprints was developed by a US physics professor as lightweight and versatile plagiarism detection software. It was introduced to me by a textual scholar who had utilised it to find quotations and repeated turns-of-phrase in literary works as part of his author attribution study. The programme can be run with either a graphical user interface, at a slightly greater overhead cost, or on the command line using a configuration file. In both cases, it allows the user to customise the exact parameters under which it will detect a “hit”. This allowed me to filter out false positives without manual examination. However, devising the best set of parameters took a great deal of trial and error.

I first ran an entire year of issues with the most forgiving set of parameters possible, a small word count (10) and a large percentage of errors forgiveness (50%). This resulted in thousands of entries and after a manual examination of a small sample I found most of them to be invalid.

Based upon my previous work, which anecdotally suggested that domestic British reprinting took place within a month, I limited the temporal range to three calendar months; because of the formatting of dates, I could not specify four weeks directly. I then increased the word count requirement to 200 words—again anecdotally based upon the smallest size article I had seen reprinted—but maintained the high error forgiveness percentage to account for articles that had omitted text rather than being truncated at the end.

This resulted in a more manageable list. Taking a small date range across both sets of results, I determined that almost no true hits had been excluded by the new parameters while nearly all the false positives had been. This level of noise reduction, erring on the side of false positives, was deemed sufficient in terms of word count. Examination of the dates found that the actual limit was closer to two weeks, and this time frame was used as a second-pass filter before analysis, removing additional false positives.

This methodology provides similar but distinct results from the Viral Texts project at Northeastern University, which makes use of the self-designed Passim software. Passim utilises pre-processed text files and is more focused upon finding individual passages of repeated text rather than large-scale instances of reprinting within a single page. My methodology, born partly out of necessity (the software and data format available to me at that stage of my research) unexpectedly provided results that suggested branching dissemination pathways as a result of a bias in results in favour of large blocks of reprinted text on a single page, comprised of several articles, over smaller individual instances.

The unit of analysis was shaped by the nature of the machine-readable texts. Developed to support full-text searching through a graphical user interface, rather than raw analysis of the text, the dataset first required cleaning. The raw data was transformed from XML into plain text, removing metadata and creating a collection of page-level units of analysis. These files, owing to their creation through optical character recognition, contained a significant number of transcription errors. Rather than attempt to retroactively correct these errors, a highly flexible piece of open-source plagiarism detection software, Copyfind, was used to identify matching texts.18 Individual pages were compared against each other on a month-by-month and a month-by-succeeding-month basis, producing a list of likely instances of textual reappearance—a match of at least 100 words per page in clusters of at least 20 words each. These manifests were regularised for the typical two-week domestic news-cycle while same-title matches, which were almost exclusively advertisements, were filtered out.19 These lists were then processed to determine the average word count of a match as well as the percentage of each page and issue that included duplicate text.20

The first analysis undertaken for this project was the creation of a century-long manifest of instances of duplicate text within the entire run of the British Library’s 19th-Century Newspapers. It was a rough visualisation of this material, a layered bar chart (hits within 100-word ranges, over time), that I first presented to colleagues at our initial symposium. The concern at that stage was the lack of specificity regarding titles, periodicities, layouts and topics. The raw number of computational matches, moreover, seemed very low compared to material that could be identified manually for a given issue. It was therefore suggested that a finer grain analysis be undertaken to tease out more of the meaning behind these textual reappearances. As examining and processing the millions of individual hits manually was impossible, additional filters and heuristics were needed to meaningfully leverage the advantages of computational reprint identification.

The results of these analyses support anecdotal evidence that the Chronicle, the Examiner, and the Mercury had an unusually high level of textual reappearance between them.21 These newspapers all fall under the general heading of liberal or reform publications—though the Examiner held more explicitly radical views than the “moderate constitutional liberalism” of the Morning Chronicle and “Whiggishly inclined” Caledonian Mercury—so this degree of overlapping text was not unexpected.22 Despite this, the distribution and nature of textual reappearance varied noticeably between them. Measured by raw word count, the number of words that could be found in an earlier publication, the Examiner deviated the most from the corpus average. In the Chronicle and the Mercury, approximately 55% of matches fell into the range of 100-400 words, evenly distributed, with higher word counts appearing in decreasing frequency. In contrast, over 75% of the Examiner’s pages fell into this range. This discrepancy is most readily explained in the larger number and smaller size of its pages. For the Chronicle and Mercury, which had similar page sizes and overall word counts, the average length of a matched textual unit—likely representing an article—was 200 words, the same as the corpus average. Throughout the corpus, 1840 saw a marked decrease in the percentage of matches under 300, a more even distribution in the number of matches between 100 and 600, and a significant rise in the number of matches over 1000—a trend that merits specific consideration when undertaking a close reading of these issues. Of the three publications, the Mercury most closely mirrored corpus averages across the period.

When I began this project, I had considered the relative merits of working primarily with a Scottish periodical, of which my contextual knowledge would be far greater, versus a London periodical, which might be more useful to a wider range of researchers, or some sort of representative national sample. As a result of my earlier studies, I was more familiar with the Chronicle than other London publications, owing to its status as primary metropolitan source for many articles published in Scotland, and with the Examiner, owing to it frequently reprinting from other publications in general. Taken together, they also represented a strong anecdotal network of reprinted content, at least on those topics I had researched previously. I, therefore, undertook low-resolution analyses of these three publications in order to establish them as being either in the upper or lower end of reprinters and to qualify my later results appropriately. That both London periodicals proved to be interesting outliers, and the Mercury appeared to track the median results of the corpus as a whole, was largely a happy accident— one that allowed me to answer different and, in my opinion, more interesting questions than I had originally aimed to address. For this reason, I would suggest humanities researchers plan to undertake multiple distinct, iterative analyses, and allow their research questions to evolve after each stage—without retroactively fitting questions to results within a single iteration.

These word counts are given greater context by contrasting the percentage of each issue that was identified as duplicate material. Again, the results from the Examiner vary significantly from the Chronicle, the Mercury, and the wider corpus. In the latter three, over two-thirds of the issues had fewer than 6% of their content marked as duplicated text, with the strongest clustering around 1-3%. The Examiner, conversely, clustered around 10%, with roughly 15% of its issues registering over 15% of their text as duplicate material. As a self-styled “weekly review”, these higher percentages are to be expected, even if they appear anomalous within this particular corpus. Taken as a whole, the computational analysis suggests that the occurrence of duplicate material was similar between titles of similar periodicity, scaling logically between weekly and daily publications, and that preponderance of pages from daily newspapers within the corpus biased the average percentage toward that found in the most frequent publications. This highlights the value of pre-processing collections into sub-corpora, ideally over multiple iterations with differing criteria, in order to isolate meaningful trends. Despite these inconsistencies, an average of 3-4% of each issue of the Mercury was computationally identified as duplicate material, making it largely representative of the corpus’s more frequent publications; it is with this baseline figure that we shall compare our close readings to determine the general accuracy of computation matching.

As has often been the case in my career, the full understanding of where a piece of research fits within the existing historiography became apparent during the writing process. Although I had undertaken a diligent review of histories of these publications, of editorial practices for the relevant periods and of the growing literature on reprinting in 19th-century newspapers, it had been some time since I had read through general texts on the nature of the newspaper as a medium. While writing the first draft of this article, in its current configuration, I was undertaking unrelated research in the National Library of Australia and had begun to read a series of general texts on the history of the Australian press, largely written by 20th century newspapermen. Upon leafing through Henry Mayer’s The Press in Australia, I was surprised to find manually composed tables that were nearly identical in format to my own. Sharing an earlier draft of this section with the special issue’s editor, he was reminded of a similar piece by Clark and Wetherell, which I dutifully obtained and found, once again, a series of similarly formatted (if dissimilarly populated) tables.

After the initial shock, I found this fascinating and spent a great deal of time considering the different approaches that had been taken in all three cases, not just owing to differences in archival and computational access. In the end, it provided me the opportunity to consider the relative merits of three systems that had been independently created to answer similar, but not identical, research questions and the extent to which I should reconsider the shape and criteria of my interpretive categories. In particular, I had to justify to myself the value of, at least in this iteration, measuring by OCR wordcount rather than column inches, which was the more common method. Although I still feel my approach has merit, and I genuinely sympathised with compositors after years of hand transcribing texts for rudimentary computational analysis, Quintus van Galen, working with positional metadata, has argued persuasively for a return to “column inches"in future iterations of this research, bringing in the wealth of research on newspaper materiality that is lost when focusing solely on disembodied text.

A Close Reading of the Caledonian Mercury

A close reading of an issue can focus on the text, images, marginalia, or other manuscript marks; it may also include an examination of the physical layout and the materiality of the item. In this study, close reading entails the dissection of the issue, the careful examination of the text to disambiguate, categorise and number individual textual units by type, topic, geography, source and word count. This type of newspaper anatomy has several precedents. In The Press in Australia, Henry Mayer dissected “twelve random copies” of the Age and Melbourne Herald for 1855, 1875, 1900 and 1925, cataloguing the average percentage of physical space given to different content types as well as the coverage of various broad topics.23 From these, he argued that such samples were always in danger of producing misleading trends, with layout and composition fluctuating dramatically in response to changes in “news-values and [the] accessibility of news.” In contrast to this broader survey, Charles E. Clark and Charles Wetherell’s study of the Pennsylvania Gazette offers a detailed discussion of a single title.24 In it, the authors measure the column inches dedicated to different content types and topics, as well as the geographical distribution of stories (by place of action) and their average delay in publication (from time of action). Of particular relevance to this study is their discussion of sources: other publications, correspondence, and oral communication, with the first providing at least 66.4% of the Gazette’s news content.25 Although they had to rely upon explicit attributions and deduction, the degree to which they were able to infer the interconnectivity of colonial American and European newspapers is impressive. By using similar categories, but substituting word count (and, in some sense, compositor effort) for the measurement of physical space, it is hoped that the present study will complement to previous close readings and provide new perspectives on how to conceive of the composition of a newspaper.

As for the choice of the Mercury itself, the wider applicability of this dissection can be seen through the anatomy of a Georgian newspaper put forth by Francis Williams:

The normal format was a single sheet of 24 1/2 inches by 18 3/4 inches folded once to produce a four-page paper in folio 12 1/4 inches by 18 3/4 inches. Each page was made up in four columns printed solid with the minimum of headings. The news offered consisted normally of summaries of Parliamentary debates, foreign intelligence copied from Continental papers, Court intelligence, reprints of the London Gazette, brief reports of decisions in the law and police courts and a certain amount of commercial intelligence. In addition as general readership grew there might be a medley of gossip paragraphs about those in the public eye, a column of jokes and epigrams on social follies, notices of new plays, some verse and a 'Letter to the Printer.'26

Based largely on the London dailies, this summation is equally representative of the Mercury between 1820 and 1840. It, too, was composed for four pages, printed on a single sheet, though with more columns, growing from five in 1820 to seven in 1840. Its content can, likewise, be placed under the same general headings, though these were perhaps more constricted in any given issue owing to its less frequent publication. Although any delineation is contentious, the Mercury contained four general categories of content and their appearance on certain pages was consistent across the period:

As suggested above, the four categories listed here were not those originally envisioned at the start of either my first large-scale or my initial close reading analysis. While advertising may seem uncontentious, the placement of non-commercial notices as either advertisements (which they resembled in form and multiple publication) and news (which they resembled in purpose) was a subjective decision. Likewise, although miscellany—such as poetry—and editorial commentaries had previously been separate categories, they were so alike in their patterns of reappearance and attribution practices, and so numerically uncommon compared to news and advertisements, grouping them together provided more meaningful results. As for numerical content, my editor and I corresponded at length to agree upon a meaningful title for this category, which includes local and metropolitan shipping notices, market and stock prices, weather information and census data. In the end, their grouping was largely based on their similar use of tables and ellipses, which OCR scanning was rarely able to accurately reproduce.

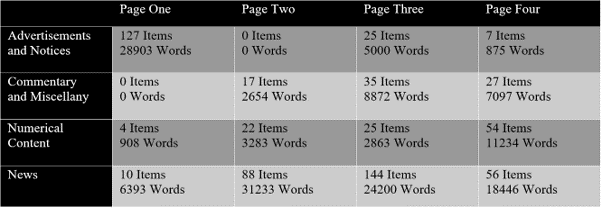

Table 1

The combined item and word counts, by page, of the four main types of content printed by the Caledonian Mercury in the sample issues.

Much of the information gathered here was originally derived from conversations with newspapermen and others with hands-on compositing and printing experience and rarely appears in academic works. Had I not had the opportunities to speak informally to individuals at the American Antiquarian Society, the Museum of Printing or the Wai-te-ata Press, I would have not understood the meaning behind the Mercury’s deviation from practical norms of the period. Although it is very minor point in the context of this study, these oral histories, like my experience of typesetting small runs of text, have influenced the associations and interpretations I arrive at in my analysis of the computational data, reminding me of the additional and absolutely necessary layers of subjectivity that are required when working with big data.

The front pages were principally composed of advertisements, stock prices and other formalized notices. Across the period, only 7% of the individual items could be categorised as news content and these appeared only in the 1835 and 1840 issues. Although advertisements were never wholly confined to this page, their place here represented a standard feature of the Mercury throughout the period. Page four, the other outer page, was more varied. Of the 144 individual items, 19% were commentaries or miscellany, 39% were news items from local, regional, national and international sources, and the remaining 42% were advertisements, price lists or other numerical content. As the period progressed, the relative percentage of news and miscellany increased with numerical and advertisement notices remaining largely confined to the final two columns despite an increase in the number of columns per page. The mechanics of printing a four-page, single-sheet newspaper allowed the setting and printing of the outer pages of the issue first, leaving the inner sections for more recent reportage.27 This idea is plausible for the Mercury before 1835, with the inner and outer pages presenting distinct content, but is incompatible with the later issues, where parliamentary reports frequently ran across the first and second pages and information derived from recent London newspapers appeared on the back page. Even in the earlier issues, the chronology of reportage across all four pages, and the insertion dates of advertisements on the first, suggests that the inner and outer pages of each issue were set and printed at roughly the same time.

The tension between providing a widely applicable predictive model, which relies upon abstraction, and a meaningful interpretive model, which relies upon individual contextual fit, is something raised by all robust academic histories. Although the size of my sample was comparable to those undertaken by other newspaper historians in similar studies, I wanted to ensure that these percentages were at least representative for the Mercury as a whole. In the end, it was impossible for me to assert uniformity across issues except at the low resolution of a yearly average. This note, therefore, was a recognition that the model will likely not be accurate for any given issue but would hopefully remain generally predictive for yearly analyses. As texts produced at scale, both in terms of size of individual runs and the frequency of publication, this level of variation, and the requisite averaging, is perhaps more acceptable in studies of newspapers than for monthly reviews or annual publications but should nonetheless be taken into account when applying the model more widely.

The inner pages consistently contained most of the news content. Page two allocated over 60% of the items and 85% of the word count to news content, nearly all of which referred to the royal family or Parliament. The remainder came from the London Gazette, as Williams noted, discussing recent appointments, bankruptcies, and stock prices. Similarly, 63% of the items appearing on page three were categorised as news, though with a more even split of metropolitan (32%), Scottish (36%) and international (11%) coverage. The remainder of items were local advertisements or sponsored content (11%), numerical content (11%), and commentaries or miscellany (15%). Between 1820 and 1840, the Mercury saw an increase in parliamentary coverage and commentary, and its concentration on the second page, with a commensurate decrease in inner-page advertisements—only a handful appeared in the 1830s and none in 1840. Soundings from other seasons suggest that despite cyclical fluctuations in shipping, politics and commerce, the distribution of content was relatively consistent year-on-year, making it suitable for computational analysis.

There were two main principles that went into the development of my method of categorisation. First, I wanted my category system to be broad enough that even a relatively small sample size would produce clear trends. This is apparent in both my genre classification as well as my ability to abstract attribution types into broad categories such as location, unnamed publication, named publication and named individual. The other principle was an adherence to quoting and annotating data rather than entering it in abstract form. By using direct quotations, the material can be recategorized at higher and lower resolutions during later iterations or repurposed as a base for alternative research queries. Releasing the data open access therefore allows both interrogation of my interpretations for this project and reuse by other researchers. During this project, I experimented with several different resolution types before settling on the set depicted.

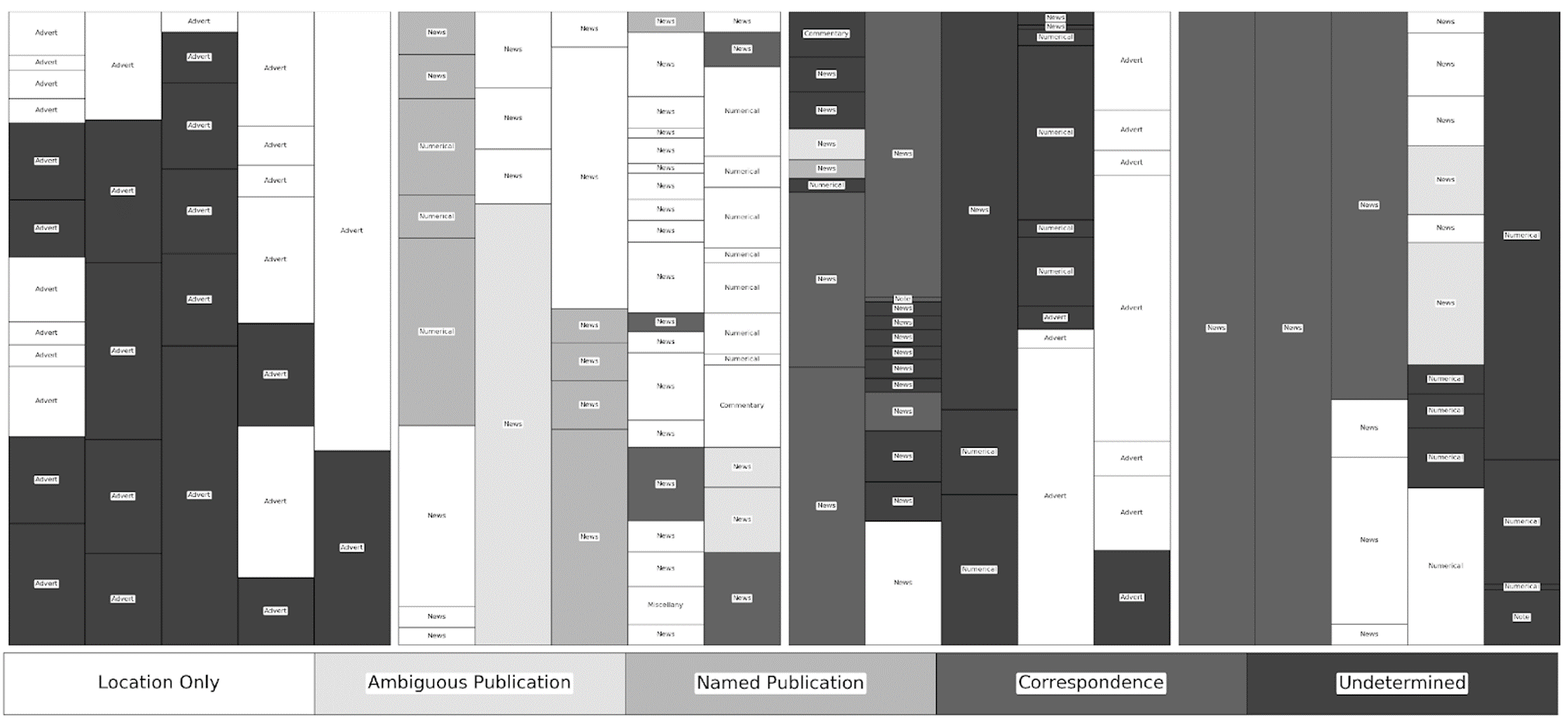

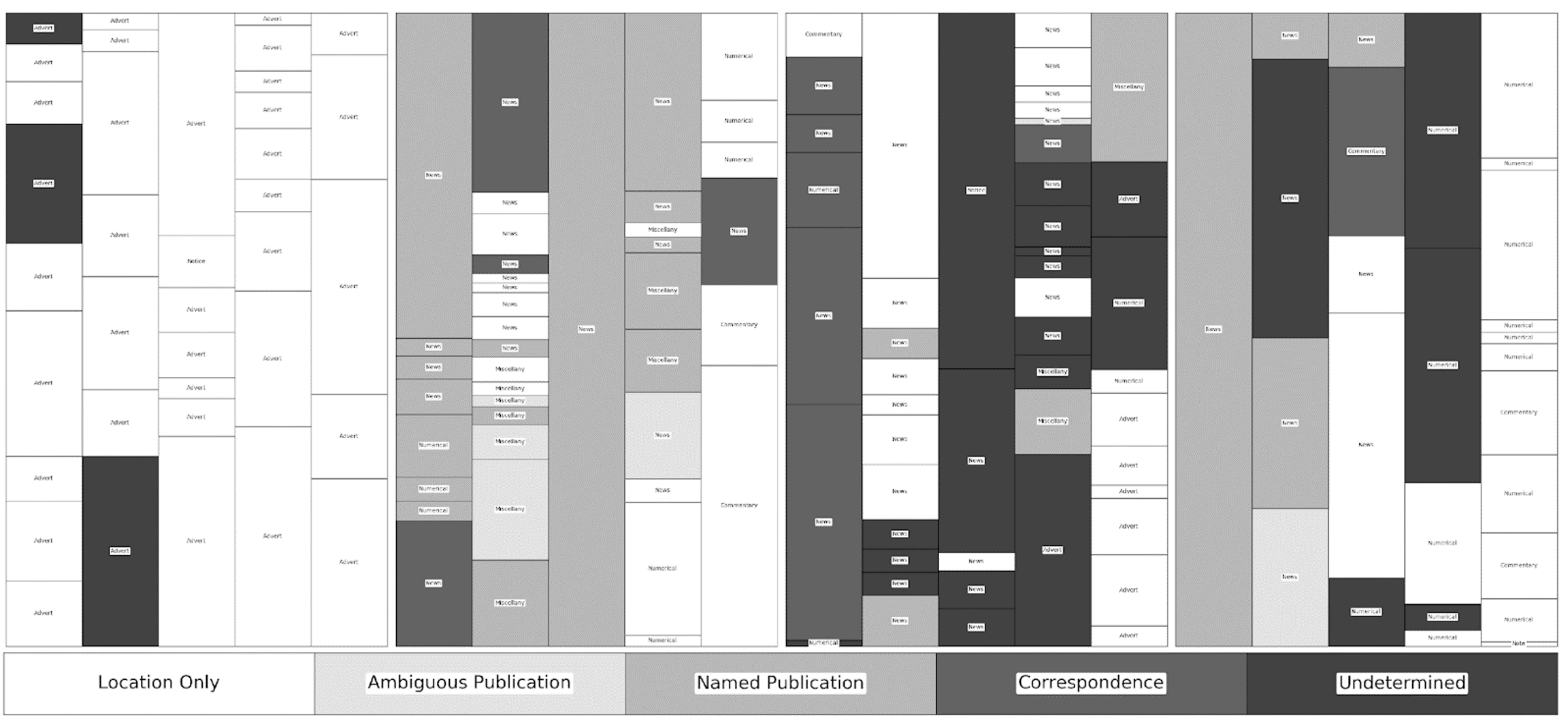

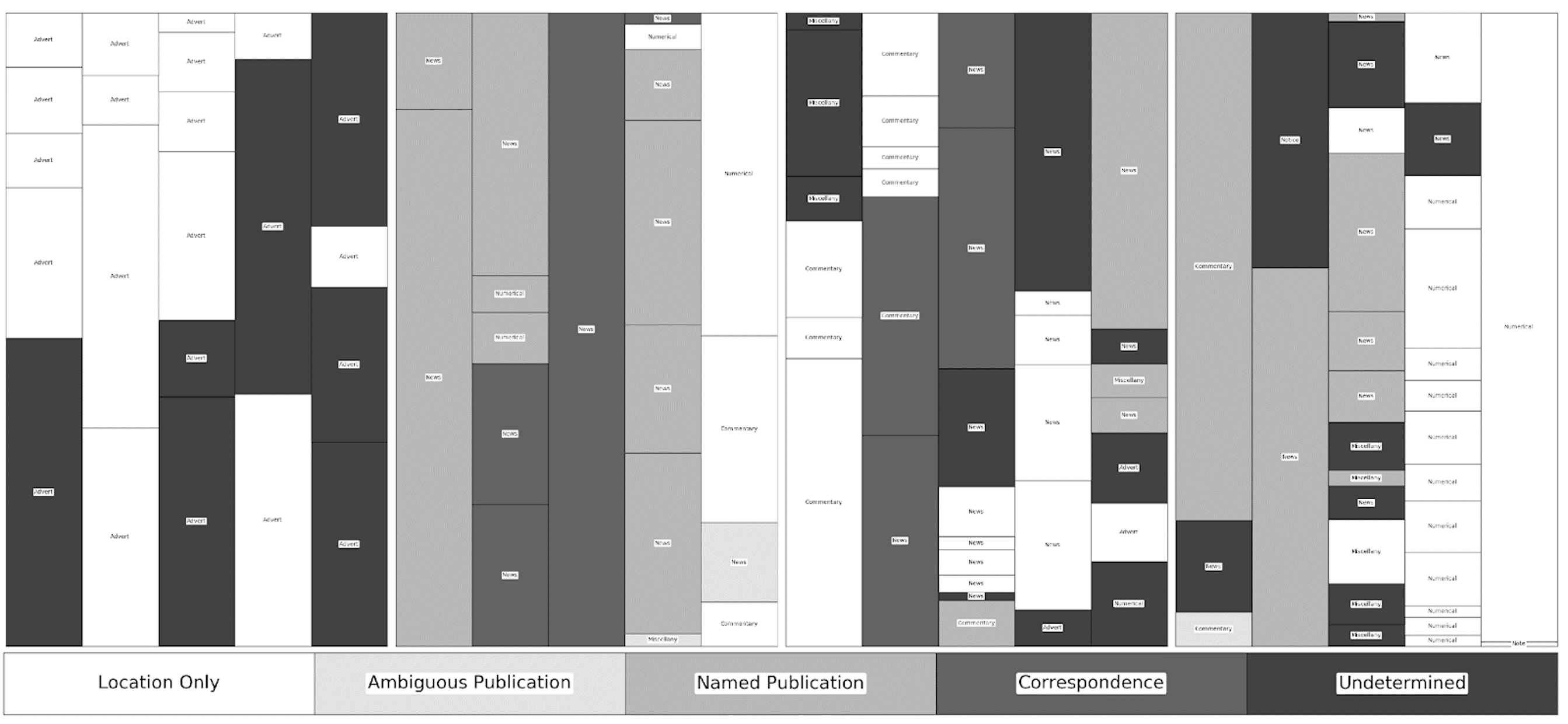

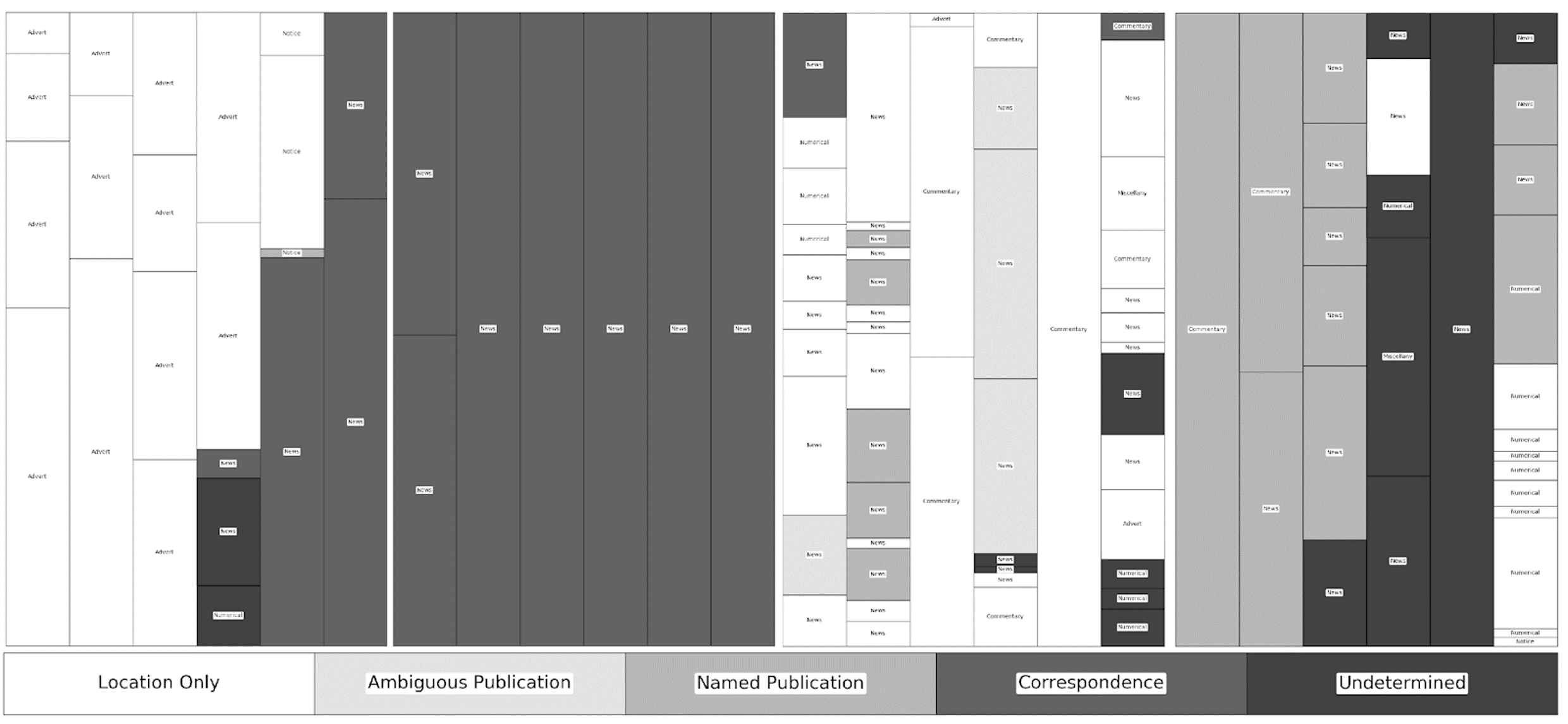

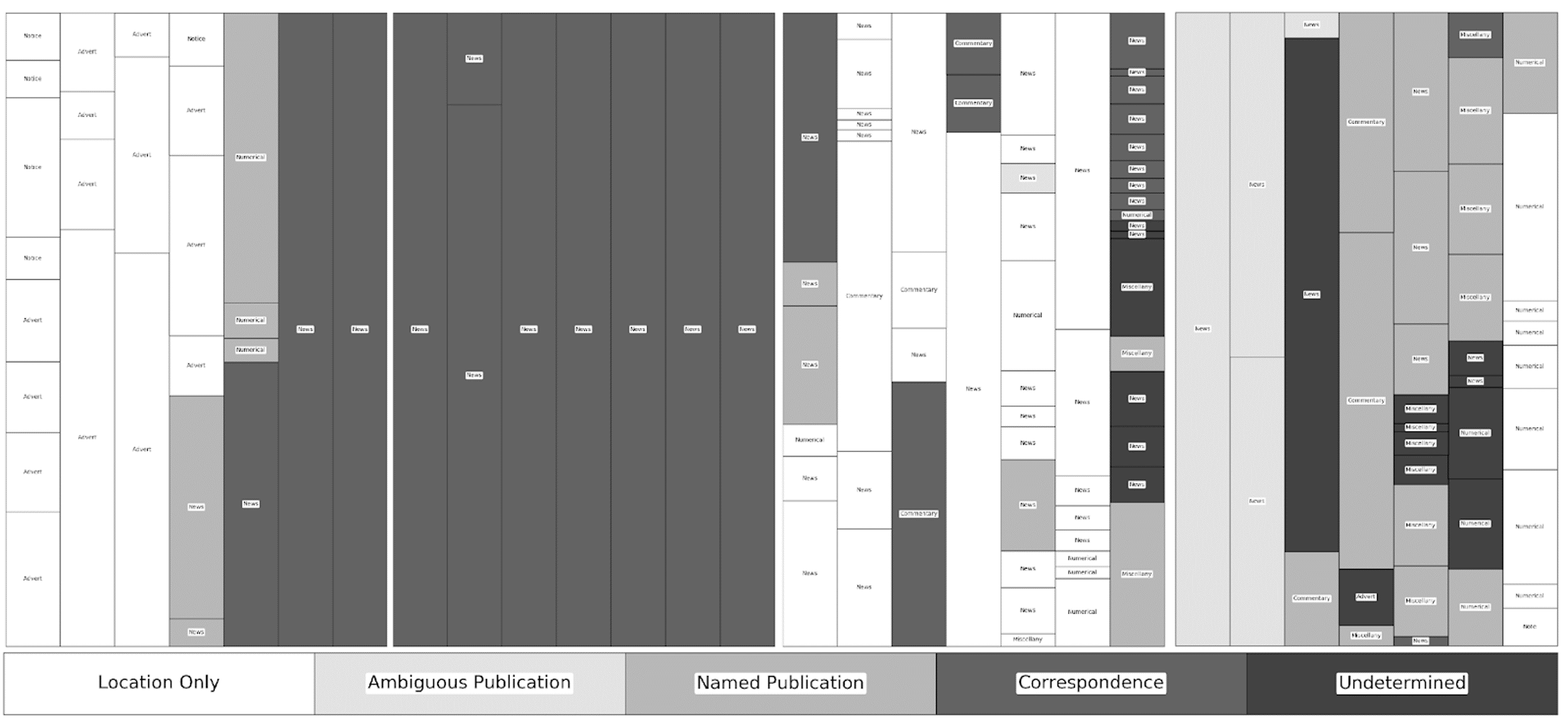

The relationship between content and placement is immediately clear but a finer cataloguing suggests additional correlations with curatorial and attribution practice. Cataloguing began with the disambiguation and numbering of individual texts (hereafter referred to here as snippets) by page number, column number (left-to-right) and snippet number (top-to-bottom). These snippets were then coded for five characteristics: the type, the topic, the location of the action discussed, the source of the material, and the word count as determined through optical character recognition. Type was separated into five fixed categories—advertisements and notices, commentaries, miscellany, news, and numerical content—while topic was left open ended. Place of action, derived from a close reading of the snippet, was only entered if explicitly mentioned and left at the resolution of that reference—leading to some locations being listed as a country and others as a province or city. The source of the material was recorded as either the specific title, an ambiguous title such as “Paris papers”, the name of the correspondent, or the location at the resolution given. In this period, the Mercury had very few decorative elements to indicate different sections or textual units and I have relied upon my judgement regarding shifts in topic, as well as typographical and semantic clues, to determine where one snippet concluded and another began. Once the snippets were fully disambiguated and coded, they were re-visualised to provide a simplified facsimile of each page, depicting the placement and length of each snippet, and shaded to represent different sources types, allowing for a visual comparison of different pages within and across issues. The results provide a basis for understanding the standard practices of curation—the use of previously published material— and attribution in the Mercury.

The visualisations depicted here went through several iterations before publication. In order to better understand attribution and topic patterns during my initial close reading, I created a series of Excel formulas to normalise OCR word-count data as a percentage of a given column. I then visualised this information using a 100% Stacked Column graph, customising it to reduce the space between columns to zero. Although the resulting visualisation looked similar to the current iteration, it was time consuming to input and customise each graph, owing to the inconsistent number of items per column and page.

While attending an event hosted by the Software Sustainability Institute, I had an informal chat with two mathematicians regarding my current project and they suggested using the MatPlotLib for Python 3 as a way to both improve the customizability of my graphs as well as increase the efficiency of the data translation process. After a few hours, the three of us arrived at an initial prototype of the Newspaper Dissector. Conversations continued for several weeks thereafter to fine tune input and display mechanics.

During the proof stage of publication, however, I had to revisit the programme in order to produce three colour variants of the charts. One utilised a standard five-hue colour scheme that was visually appealing to those with a full-colour range. A second utilised a five-value greyscale palate for hardcopy visualisation. This was originally done through pattern, rather than values, but the resulting visualisations were unintelligible at the print resolution. The final variant was created to be intelligible to those with red-green colour blindness—something I have anecdotally found to be extremely common in the digital humanities. The five colours were based upon those recommended in the academic literature on accessibility for colour-blind readers and tested by a number of colleagues through social media networks.

Figure 1

Re-visualisation of the Caledonian Mercury for June 15, 1820, shaded by source type. High-resolution and full colour images and associated data available at http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.5998502.

Figure 2

Re-visualisation of the Caledonian Mercury for June 16, 1825, shaded by source type. High-resolution and full colour images and associated data available at http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.5998496.

Figure 3

Re-visualisation of the Caledonian Mercury for June 14, 1830, shaded by source type. High-resolution and full colour images and associated data available at http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.5998493.

Figure 4

Figure 4: Re-visualisation of the Caledonian Mercury for June 15, 1835, shaded by source type. High-resolution and full colour images and associated data available at http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.5998454.

Figure 5

Re-visualisation of the Caledonian Mercury for June 15, 1840, shaded by source type. High-resolution and full colour images and associated data available at http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6011597.

Although the Caledonian Mercury was a major newspaper in Edinburgh for the period under study, and its inclusion in the early digitisation programmes of the British Library made it particularly accessible for a variety of research projects, there remain relatively few official records of its business practices. Likewise, unlike newspapers that continued into the 20th and 21st centuries, or those with editors or owners of wider historical interest, there has been little academic literature written on the title. Therefore, my most reliable source of information about the publication was its imprint, a legally required statement of ownership and editorial liability that appeared on each issue, and contemporary commentaries on it by other publications.

By utilising the search functionality of Google Books, which has digitised hundreds of monthly and annual literary periodicals from this period, I was able to piece together a number of asides—many of them humorous or acerbic—about the newspaper and its editors. Although fragmentary, it did allow a general sense of trajectory with which to frame my own content analysis. Moreover, the creation of this institutional history was excellent practice for another project I have since undertaken, The Atlas of Digitised Newspapers and Metadata, which also involved piecing together ephemeral and unofficial commentaries.

Direct comparison across these years has two specific caveats. First, although Allan remained the owner of the Mercury, he was not involved in the daily running of it, leaving its management to the editor, who changed twice during the period: in 1827, James Browne was appointed, after which contemporaries commented on a rise in early reports; in 1838, the editorship fell to “a knot of young Whig lawyers, suckling politicians and expectant commissioners, who, gratuitously, it is said, furnish the requisite 'leaders.'"28 These changes mark three distinct eras in the sample period. Second, the 1840 issue was atypical in content owing to coverage of the attempted murder of Queen Victoria, which saturated the Mercury and other newspapers throughout the country, skewing the relative percentage of duplicate material from London. Yet, even with these caveats, clear patterns are visible, providing new insights into the general composition of the newspaper.

Once I had entered attribution data into my spreadsheet, I had two principal queries for it. First, I wanted to understand the physical patterns of information dissemination I was observing, where had the information come from and by which paths had it arrived in Edinburgh. This was largely achieved by differentiating between the place of action, upon which Clark and Wetherell had relied, and the places of attribution that were explicitly provided. From experience, I knew that these explicit pathways were usually incomplete, missing intervening points of republication, but they nonetheless provided some understanding of the route taken. In this examination, I had to be aware of two biases in my thinking. First, having explored Borders-Lothian publication networks at length in my PhD, I had to be careful not to make assumptions about the pathways with which I was more familiar so as to provide a consistent analysis across all content. Second, I had to stop myself from normalising the resolution of attribution information. While an account about London, which had many nationally distributed newspapers, was likely an account from London, this was not explicit in the evidence; any inference needed to come after the data collection stage and not before. These conscious efforts to maintain a “quote and annotate” data collection practice allowed me to recognise the overwhelming use of location rather than institution-based attributions and from this to make initial inferences about the role of readers in adjudicating reliability via the proxy of source location.

First, providing an attribution of some description was the standard practice, with over 80% of non-advertising material containing some indication of its source. However, the spatial placement of these attributions varied without correlation to topic or type. They sometimes appeared as explicit lead-ins, tag lines or narrative attributions; other times they were implied through a heading preceding multiple items, particularly in the case of local or regional news. The purpose of attribution is implied by relative proportions of attribution types. 60% of attributions were to geographical locations, through datelines or other textual references, rather than to specific publications or individuals. Moreover, nearly all items lacking an attribution provided a specific British location of action, implying that the material was obtained from that location. This suggests that the main purpose of attribution was to signal the physical rather than intellectual source of the information, to foreground the likelihood of its accuracy without the need for evoking the reputation of individual reporters or institutions.29 Its use also suggests that early nineteenth-century readers were expected to have or to develop a sense of practical communication distances, as well as the importance of certain locations in the political and economic landscape, in order to properly weight conflicting, anonymous accounts.30 Local and regional material presents a distinct case. The Mercury drew local content from a significant hinterland, including Edinburgh, the port of Leith, and rural Midlothian, as well as from Perthshire, Fife and the eastern Borders, with whom Edinburgh had long-standing economic connections. News from these regions were generally attributed implicitly by reference to the place of action or through the suggestion of direct communication with the newspaper’s editor, being placed beneath a sectional masthead reading Caledonian Mercury. The likelihood that these stories were obtained through oral transmission and personal correspondence makes disentangling direct reportage from unattributed duplicate material seemingly impossible for local items.

My use of percentages here was not a decision I came to lightly. In previous studies, historical and pedagogical, I had had lengthy discussions about statistical significance and the obscuring effect of reporting percentages of small sample sizes. In the end, my editor and I agreed that inclusion of both absolute numbers and percentages in embedded tables, alongside the open access release of my entire dataset, would offset any misinterpretation that results from streamlining the flow of narrative text. Nonetheless, I did endeavour to make explicit noteworthy absolute numbers, such as the one piece of society news or two parliamentary commentaries listed here.

When the Mercury did indicate that duplicate material came from another publication, it did so with either the title (77%) or the location of the publication (23%). In both cases, London was the most prevalent source, with 50% of titles and 37% of location-based attributions. The remaining attributions were divided between Scottish (19%), provincial British and Irish (11%), and international or colonial (11%) titles as well as a smaller number (9%) of monthlies and separate publications, including books and pamphlets. Across the five issues, few publications were mentioned more than once, the notable exception being the London Gazette to which nearly 5% of all non-advertising snippets were attributed, most of them appearing under a heading naming that publication. Distinguishing by category, approximately 25% of news items were attributed to a publication, whereas only 14% of numerical content and notices were—all of which came from the London Gazette and Lloyd’s List. By far the most likely to be attributed to an earlier publication were commentaries, miscellany and human-interest stories, which may have been considered creative or analytical works and therefore garnered greater legal protections or moral rights, a notion requiring further research. The prevalence of attributing miscellany material may also help account for the relatively low percentage of attribution in 1820, which included only one item of society news and two short commentaries on Parliament and the royal family, attributed geographically or not at all.

One of the greatest challenges of working with new digital methodologies is the number of minor and preliminary conclusions I came to during my iterative analyses. This paragraph, for example, was largely focused on relating the main conclusions of my article, the overall percentage of textual appearance within mid-century newspapers and the degree to which it could be identified manually and computational. The paragraph was the result of more than a year’s worth of detailed research and I am still somewhat ambivalent about my ability to so succinctly describe the results of so much research. Conversely, the second conclusion, on the correlation between individual editors in the percentage of textual reappearance, was largely speculative and preliminary, and yet required significantly more space to put across. I would not, even at this stage, have reallocated my word count differently but the experience serves as a reminder to me of the poor correlation between research effort and publication word count.

If we include only snippets that are in some way attributed to another publication, we find that an average 21% of each issue, as determined by OCR word count, was duplicate material, a significantly higher proportion than the corpus average of 3-4% discovered with Copyfind. The average wordcount of these snippets was 380, at the high end of our expectations, with only a single piece over 1000—suggesting that increase in matches over 1000 words at the end of the period indicates the use of multiple snippets from a single source rather than the reuse of a single long snippet.31 The 1840 issue, despite a change in editorship and the extended coverage of the attempted regicide, contained the same proportion of explicitly duplicated material; only the 1820 issue contains a lower proportion (11%), explained by the relatively high proportion of private correspondence used. As for the correlation between Browne’s editorship and an increase in early reports, this sample failed to capture any significant decrease in the amount of previously published text, although the space provided to Parliamentary correspondence did increase.

Although largely an apologetic for the limited applicability of my results to the study of Scottish periodical networks, looking back on this paragraph now serves as a call to initiate a further iteration of this project, taking advantage of recent digitisation by the British Newspaper Archive as well as the forthcoming digitisation programme of the National Library of Scotland. Since writing this article, I have undertaken a significant study into the newspaper digitisation projects of ten national libraries and I believe that my frustration and concerns about “Close Readings of Big Data” greatly influenced my subsequent research agenda. I, therefore, wish I had been more honest and genuinely forward looking in my analysis here, treating my publication as an intermediate, iterative stage of research and not as a summative look back at iterative research that had now concluded.

Finally, the paucity of Scottish titles within the corpus may also help account for the disparity between the manual and automatic identification of duplicate material. Across the period, fourteen different Scottish newspapers were explicitly attributed, including the Aberdeen Journal and Glasgow Herald, which were included in the corpus. Of the others, only the Perth Courier has been fully digitised for this period, as part of the British Newspaper Archive. Most of the others have been digitised but only for the period after 1840, while the Galloway Register, Glasgow Chronicle, and Glasgow Courier remain un-digitised. However, the items attributed to Scottish newspapers tended to be short in comparison with overseas or English content, representing only 11.1% of publication-attributed snippets and 2.3% of the entire sample, and many fell below the minimum word count set for automatic identification. The exclusion of Scottish titles from the corpus is, therefore, unlikely to have a significant negative effect on the overall computational analysis.

Having examined the sample in detail, we are left with the following conclusions. First, the automatic identification of duplicate material appears to have consistently returned only 15-20% of attributed, and ostensibly duplicated, material. Second, over 80% of non-advertising items were in some way attributed, with roughly 25% giving the name of the source publication. Of the latter, numerical items were relatively less likely and non-news items relatively more likely to be attributed than the average. Third, change over time and editorial control appears to have minimally impacted the percentage of attributed material. Finally, the geographical composition of the corpus does not appear to have significantly biased the likelihood of computational identification.

Much like my conclusion on the close reading portion of my project, this paragraph goes through several important interpretive statements in quick succession without a clear connection to the level of curation and mediation that went into them. Conclusions about the general chronology of dissemination within Britain were based upon a final iteration of computational reprint detection that was itself based upon a corpus that had been filtered by my own specific, deliberate, and contextualised choices and processed by protocols that I had developed based upon a manually curated dataset. These had, in turn, been created from an unsupervised statistical sampling of a corpus that had been meticulously curated by librarians and digitisation specialists wholly unrelated to the project. It is for this reason that my final conclusions are abstracted to the highest resolution at which they remain both generally predictive and interpretively meaningful, given these various stages of statistical and manual curation. My final sentence is an explicit refutation of an early claim I had made in conference and seminar papers as I had gained a fuller appreciation for the limits of large-scale predictive modelling during this project.

Extrapolating from Close and Distant Readings

When computationally compared with the wider corpus of digitised newspaper content—all pages from the months of May, June and July—ninety-four instances of duplicate text were found. Of these, twelve (12.7%) were false positives, pointing to similar but non-identical parliamentary transcriptions, and one was an outright false positive. From the opposite perspective, 10% of the items catalogued in the sampled issues were shown to have also appeared in other newspapers within the corpus. Of these, only 47% were matched to publications that were dated at least two days before the Mercury; the remainder were printed either simultaneously or subsequently and therefore cannot be inferred as a possible source of the material. Thus, within these specific issues, roughly 5% of the items and 3.8% of the word count were plausibly matched to a source within the corpus, similar to the initial 3-4% estimate but far below that calculated by close reading. Moreover, unless one generously matches vague attributions such as “London Papers” to specific metropolitan titles, no source was confirmed by both explicit attribution and computational matching. For example, a small number of pieces attributed to “London” or without attribution were found in previous issues of the Times and Chronicle but none of the texts explicitly attributed to the Chronicle or Times were found automatically owing to their short length.32 This suggests that some items were popular enough to appear in multiple publications before appearing in the Mercury, even if their actual originator was not included in the corpus. It also introduces the intriguing possibility of a correlation between some popularising characteristic within the text and a purposeful ambiguity or occlusion of its source, similar to patterns found in urban legends. Regardless, the rapid duplication of texts within competitive markets, particularly London, the short length of certain texts, and the possibility of parallel dissemination pathways makes identifying specific lineages solely through computational matching extremely hazardous.

Later reviews of this article have presented me with the problem of identifying its true purpose. Although I have found the development of methodological practices personally fulfilling, the placement of this article within a special issue on “Copying and Copyright”, and its inclusion in national surveys such as the Research Excellence Framework, have highlighted to me the disappointment readers may feel, or indeed have felt, at the lack of definite conclusions about the Caledonian Mercury or reprinting within the British newspaper press more widely. I attempted, through thoughtful correspondence with the issue editor, to balance these two aims, though I now feel that the methodological has clearly eclipsed the historiographical in this case.

Nonetheless, I am unsure how to best reconcile these aims in the future. The removal of the methodological from historiographical publication spaces, and its isolation within specialised forums, has not served the discipline well and has largely led to static frameworks of analysis. While dual publication and cross-linking may serve to ameliorate this, it is unlikely that most historiographical readers will have the time or inclination to seek out the methodological, or vice versa, in most cases. Thus, some degree of abstraction and compression, both of methodology and historical data, may be required to allow for the true simultaneous publication of both.

Having released both the text of this article and the related data through my institutional repository, I can note, with some degree of satisfaction, that the individual charts and datasets have been downloaded at a rate of approximately 15-25% of that for the main text. While this is still relatively low, it does suggest a market for underlying research data, which I am now encouraged to fill with all my subsequent research publications.

In terms of category, 70% of computational matches were to news items, with 15% catalogued as miscellany, 12% as advertisements and 3% as numerical content. Within these news matches, two thirds of those indicating a previous printing had been given a publication attribution by the Mercury, whereas two thirds of those indicating only simultaneous or subsequent matches were attributed geographically. This suggests that at least one common source of news is missing from the corpus, and, more interestingly, that material from such sources was less likely to be explicitly attributed*.* The results also prompt speculation on the placement of the *Mercury* within the wider network. Over half of the news articles appeared simultaneously or subsequently with the corpus. If the corpus provides a representative sample, this implies that the *Mercury* existed near the centre of the dissemination timeline, receiving non-local news earlier than many other provincial publications, even if there is little computational evidence that it acted as a direct source of that material to others. As for evidence of biases within the corpus, only one locally authored story was computationally identified elsewhere despite frequent references to the *Mercury* in other Scottish publications.33 This may indicate that the *Mercury* was only used as a source by other Scottish newspapers, which were not included in the predominantly English corpus.

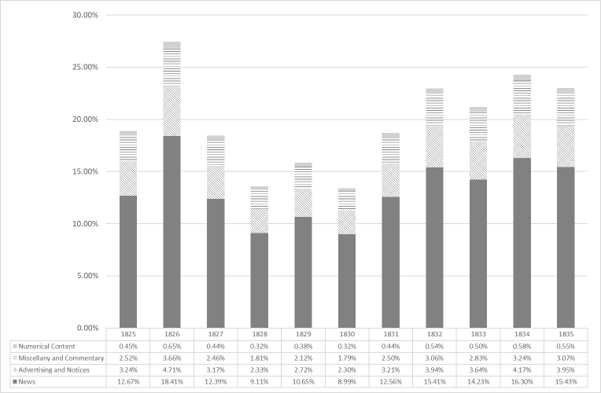

Figure 6

Likely percentage of the OCR word count of the average issue of the Caledonian Mercury for a given year to be duplicate material, shaded by content type. Data available at http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6011630.

The precise mechanics of this upscaling have been detailed in the footnote below, having originally been placed in the text and removed at the suggestion of the issue editor—a decision I agree with on the basis of foregrounding conclusions while providing easy access to the underlying analysis. Although the final mathematical processes involved in implementing a scaling algorithm were relatively simple arithmetic, the process by which I settled upon them was far more difficult than I had initially expected. I was aided in large part by my wider understanding of the contextual environment in which I was working. Many of my original conclusions were mathematically sound, in terms of raw calculations, but seemed wholly implausible given my understanding of the 19th century press. This gnawed at me greatly and forced me to independently re-devise the formula (rather than simply recalculate it) some ten or twelve times until I noticed a fundamental omission in my series of calculations. Moreover, it was not until I tested the calculation independently on several random issues from the corpus that I was satisfied of its plausibility—though not of its certainty. In the end, I only allowed myself to publish it with the hope that it would serve as a hypothesis for further research by other scholars.

Scaling these results to a wider analysis of all Mercury issues requires caution but offers tantalising results.34 In 1820 and 1840, Copyfind successfully identified 15% of duplicate items; conversely, in 1825, 1830 and 1835 it identified only 6%. When comparing word counts, the discrepancy between these dates is even greater, 17% and 44% compared with 10%. This, along with other differences in the 1820 and 1840 issues, makes it prudent to begin with a smaller range, 1825-1835. Based on the snippet catalogues, at least 21% of these issues should be composed of duplicate text. Scaling the computationally matched word count for each year by our sample-derived proportions, we find that the reality varies but roughly aligns to our sample percentage. Duplicated news content likely averaged 13% of an issue, with advertising and miscellany at roughly 3% each; numerical content, difficult to represent through OCR transcriptions, would like account for less than 1% of the computationally derived word count. Longitudinally, 1827 shows a dip followed by a slow rise, coinciding with the appointment of Browne as editor, suggesting his reputation for early reports may be merited.

Conclusions

As with all iterative processes, additional sampling will further refine these scaling factors, providing ever-more accurate representations of the Mercury and its content—understanding seasonal variations and the effect of key events being important next steps. Yet, it is already clear that iterative distant reading can provide new insights into the limits and considerations one should address during subsequent close readings and that iterative close reading is crucial for the improvement of large-scale queries.

At the start of this study, distant reading signalled the relative value of studying the Mercury over its London contemporaries, owing to its general adherence to corpus-wide trends, and highlighted the need to quantify the distribution of short, medium, and long snippets, particularly in 1840, in order to interpret the results of computational matching. Careful sampling and targeted close reading then clarified the distribution of computational matches among different snippet types and lengths, allowing new hypotheses about the attractiveness of certain traits and the specific limits of the current matching processes, increasing the value of a general reckoning of the scale of textual reappearance. It also allowed comparisons between two independently created lists of duplicate texts, leveraging the strengths of both interpretative (human) and literal (computational) identification to build the most complete catalogue possible. Moreover, correlating attributions types with the number of previous and subsequent appearances within the corpus hinted at both the completeness of the collection and the relationship between attribution and the virality of certain text types.

My final note, which perhaps was not sufficiently foregrounded here, was largely a caution against misreading “middle-scale analysis” as “humanities big data”. As I mentioned previously, these two concepts are not synonymous. My work with larger corpora has only increased my respect and appreciation for thoughtful, detailed close reading of historical material and the historical judgement and experience that is required to make meaning. Instead, I suggest that leveraging big data techniques on small scale datasets, such as a sub-corpus of larger digitised collections, may provide clearer connections to wider trends and models—something lamentably absent from many case studies—without sacrificing the immeasurable value of actually reading the texts with which you are working.

Most importantly, the iterative development and testing of scaling formulae allow us to understand the wider applicability of our soundings and samplings in new, more nuanced ways. The ambiguous and shifting definition of a newspaper in the nineteenth century often makes generalisation a counterproductive pursuit. Instead, a better understanding of correlative and interacting factors at the small scale, alongside the footprints of these at the large, may help us understand the press as something other than the sum of its parts.

Bibliography

The Waterloo Directory of Scottish Newspapers and Periodicals: 1800-1900, s. v. “Caledonian Mercury, The; (1720 - 1859),” accessed 1 December 2017, http://scottish.victorianperiodicals.com.

The Waterloo Directory of English Newspapers and Periodicals: 1800-1900, s. v. “Examiner, The; (1808 - 1881),” accessed 1 December 2017, http://english.victorianperiodicals.com.

The Waterloo Directory of English Newspapers and Periodicals: 1800-1900, s. v. “Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, The (1770 - 1865),” accessed 1 December 2017, http://english.victorianperiodicals.com.

“Scotch Newspaper Press.” The Westminster Review 12 (1830): 82-85.

“The Newspaper Press of Scotland.” Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country 17 (1838): 559-570.

Beals, M. H. “Scissors and Paste: The Georgian Reprints, 1800–1837,” Journal of Open Humanities Data 3 (2017): 1-8.

Beals, M. H. “Stuck in the Middle: Developing Research Workflows for a Multi-scale Text Analysis.” Journal of Victorian Culture 22, no.2 (2017): 224-231.

Beals, M. H. “The Role of the Sydney Gazette in the Creation of Australia in the Scottish Public Sphere.” In Historical Networks in the Book Trade, edited by Catherine Feely and John Hinks, 145-166, Basingstoke: Routledge, 2016:

Brownlees, Nicholas. “‘Newes also came by Letters’: Functions and Features of Epistolary News in English News Publications of the Seventeenth Century.” In News Networks in Early Modern Europe, edited by Joad Raymond and Noah Moxham, 349-410. Leiden: Brill, 2016.

Clark, Charles E. and Charles Wetherell. “The Measure of Maturity: The Pennsylvania Gazette, 1728-1765.” William and Mary Quarterly 46, no. 2 (1989): 279-303.

Conboy, Martin, Joad Raymond, Kevin Williams and Michelle Tusan “Roundtable Discussion of Martin Conboy’s Journalism: A Critical History, London: Sage, 2004. (x + 246 pp., ISBN 0761940995, $115 (hbk); 0761941002, $38.95 (pbk).” Media History 12, no. 3 (2006): 329-51.

Cowan, Robert M. W. The Newspaper in Scotland: A Study of ITs First Expansion, 1816-1860. Glasgow: G. Outram & Company, 1946.

Curran, James and Jean Seaton. Power Without Responsibility: Press, Broadcasting and the Internet in Britain. London: Routledge, 2009.

Curwen, Henry. A History of Booksellers: The Old and the New. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Dicken-Garcia, Hazel*. Journalistic Standards in Nineteenth-Century America.* Madison, Wis.: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

Freely, Catherine. “‘Scissors-and-Paste’ Journalism.” Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Journalism in Great Britain and Northern Ireland, ed. by Laurel Brake and Marysa Demoor, 561. London: Academia Press, 2009.

Feely, Catherine. “‘What say you to free trade in literature?’ The Thief and the Politics of Piracy in the 1830s.” Journal of Victorian Culture 19, no. 4 (2014): 497-506.

Garvey, Ellen Gruber. Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Gooding, Paul. Historic Newspapers in the Digital Age: "Search All About It!" Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2017.

Greengrass, Mark, Thierry Rentet and Stephane Gal, “The Hinterland of the Newsletter: Handling Information in Space and Time.” In News Networks in Early Modern Europe, edited by Joad Raymond and Noah Moxham, 616-40. Leiden: Brill, 2016.

Jänicke, Stefan, Greta Franzini, Muhammad Faisal Cheema and Gerik Scheuermann. “On Close and Distant Reading in Digital Humanities: A Survey and Future Challenges.” Eurographics Conference on Visualization (2015): E1-21.

Katrina Navickas and Adam Crymble “From Chartist Newspaper to Digital Map of Grass-roots Meetings, 1841–44: Documenting Workflows,” Journal of Victorian Culture 22, no.2 (2017): 232-247.

Klaus Krippendorff, Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. London: Sage, 2004.

Liddle, Dallas. “Reflections on 20,000 Victorian Newspapers: ‘Distant Reading’ The Times using The Times Digital Archive.” Journal of Victorian Culture 17, no. 2 (2012): 230-237.

Matheson, Donald. "The Birth of News Discourse: Changes in News Language in British Newspapers, 1880-1930." Media Culture & Society 22, no. 5 (2000): 557-573.

Mayer, Henry. The Press in Australia. Melbourne: Landsowne Press, 1964.

McMinn, W. G. "A Newspaper Index Report." Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 53 (1968): 69-71.

Mussell, James. The Nineteenth-Century Press in the Digital Age. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2012.

Nicholson, Bob. "The Digital Turn" Media History 19, no. 1 (2013): 59-73

Nicholson, Bob. “‘You Kick the Bucket; We Do the Rest!': Jokes and the Culture of Reprinting in the Transatlantic Press,” Journal of Victorian Culture 17, no. 3 (2012): 273-86.

Nicholson, Bob. “Counting Culture; or, How to Read Victorian Newspapers from a Distance.” Journal of Victorian Culture 17, no. 2 (2012): 238-246.

Paul, Sir James Balfour. The History of the Royal Company of Archers: The Queen’s Body-guard for Scotland. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1875.

Piesse, Jude. British Settler Emigration in Print. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Pigeon, Stephan. “Steal it, Change it, Print it: Transatlantic Scissors-and-Paste Journalism in the Ladies’ Treasury, 1857–1895.” Journal of Victorian Culture 22, no. 1 (2017): 24-39.

Rantanen, Terhi. "The New Sense of Place in 19th-Century News." Media, Culture & Society 25 (2003): 435-449.

Seville, Catherine. Literary Copyright Reform in Early Victorian England: The Framing of the 1842 Copyright Act. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Shattock, Joanne and Michael Wolf, eds., The Victorian Periodical Press: Samplings and Soundings. Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1982.

Smith, David A., Ryan Cordell, and Abby Mulle. “Computational Methods for Uncovering Reprinted Texts in Antebellum Newspapers.” American Literary History 27, no. 3 (September 1, 2015): E1–15.

Beals, M.H. "Close Readings of Big Data: Triangulating Patterns of Textual Reappearance and Attribution in the Caledonian Mercury, 1820–40." Victorian Periodicals Review 51:4 (2018), 616-639. © 2018 The Research Society for Victorian Periodicals. Reprinted with permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.

-

The author would like to express her gratitude to Will Slauter, Paul Fyfe and the participants of the Copying and Copyright in Nineteenth-Century Newspapers and Periodicals Workshop for their thoughtful comments and suggestions on an earlier draught of this article. She would also like to thank Geraint Palmer for his assistance in the development of the visualisation software employed in this study. ↩︎

-

Mussell, Press in the Digital Age, 1; Nicholson, "Digital Turn,” 61; Gooding, Historic Newspapers, 172. ↩︎

-

Shattock and Wolff, Victorian Periodical Press, xvi. ↩︎

-

Conboy, Raymond, Williams and Tusan “Roundtable Discussion,” 340. A straightforward comparison of historical and modern newspaper methods of sampling can be seen in Dicken-Garcia, Journalistic Standards, 66-7 and Curran and Seaton, Power Without Responsibility, 43, 52. For a discussion of robust newspaper sampling, see Krippendorff, Content Analysis, 111-21. ↩︎

-

Piesse, British Settler Emigration, 16. ↩︎

-

McMinn, "A Newspaper Index Report," 70. ↩︎

-

Liddle*, “*Reflections,” 235. ↩︎

-

Nicholson, “Counting Culture,” 243-4. ↩︎

-

Freely, “‘Scissors-and-Paste’ Journalism,” 561. ↩︎

-

Pigeon, “Steal it,” 27; Garvey, Writing with Scissors, 238; Feely, “The Thief,” 503. ↩︎

-

Beals, “Sydney Gazette,” 152-4; Nicholson, “‘You Kick the Bucket,” 277. ↩︎

-

Smith, Cordell, and Mullen, “Computational Methods.” ↩︎

-

Cowan, Newspaper in Scotland, 166; Seville, Literary Copyright Reform, 139. ↩︎

-

Data used in this study can be obtained from http://www.github.com/mhbeals/sap_reprints. A detailed discussion of the limits used can be found in Beals, “Scissors and Paste.” ↩︎

-

Each year, the Caledonian Mercury included a short notice on the annual archery contest and the awarding of the silver “Edinburgh Arrow”. As the event was constitutionally set for the “Second Monday of June”, it acts as a marker of cyclical similarity between the issues. The results were consistently reported in the issue nearest June 15 apart from 1820, when the archery contest was postponed to the “next fair Monday” and therefore not reported until 6 July 1820. For consistency sake, June 15, 1820 was used rather than the issue recording the contest, making the issues sampled June 15, 1820, June 16, 1825, June 14, 1830, June 15, 1835, and June 15, 1840. Paul, Royal Company of Archers, 315. ↩︎

-

Jänicke, Franzini, Cheema and Scheuermann, “On Close and Distant Reading,” 2. ↩︎

-

For publisher details on these datasets, see http://gale.cengage.co.uk/british-library-newspapers/19th-century-british-library-newspapers-part-i.aspx and http://gale.cengage.co.uk/times.aspx. ↩︎

-

For a discussion of correcting OCR transcriptions in this database, see Navickas and Crymble “From Chartist Newspaper,” 239. ↩︎

-

While the removal of same-title matches reduced the number of advertisements in the final report, advertising material appearing in multiple publications, namely those for national lotteries or patent medicines, were still captured by the automatic matching process. ↩︎

-

For a fuller discussion of the rationale behind the methodology employed, see M. H. Beals, “Stuck in the Middle”. ↩︎

-

The most likely pairing in the corpus was Chronicle with the Times, followed by the Chronicle and Examiner. The number of instances between the Chronicle and Mercury was essentially tied for third with several other provincial English pairings, but represents the most common pairing for the Mercury, as it had for the Examiner. The number of instances of textual reappearance between these three titles rose from a hundred per month in the 1820s to over three hundred by 1840. The increase over this period mirrored the increase number of pages per issue and therefore does not necessarily suggest closer linkages between the publications but rather a proportional increase in their overlapping content. ↩︎

-

“Morning Chronicle”; “Examiner”; “Caledonian Mercury”; "Scotch Newspaper Press," 84. ↩︎

-

Mayer, Press in Australia, 11-14. ↩︎

-

Clark and Wetherell, “Measure of Maturity,” 279-303. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 295. ↩︎

-

Williams, Dangerous Estate, 50-1. ↩︎

-

Huntzicker, Popular Press, 102. ↩︎

-

Curwen, History of Booksellers, 145-6; "Scotch Newspaper Press," 84; “The Newspaper Press of Scotland,” 563. ↩︎

-