Spatial Genealogies:

Mobility, Settlement, and Empire-Building in the Brazilian Backlands, 1650-1800

Citation for Original Article:

This article is a part of a broader project that examines the interiorization of the Portuguese colonization in Brazil during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Historians approached this process from multiples angles: from a regional perspective, emphasizing how mobility and frontier resources shaped local communities; through the transplantation of Portuguese institutions inland; and from biographical remarks that revealed stories of discovery, exploration, and pioneering. My experience in mapping Luso-Brazilian settlements in the backlands during this period, however, pointed out another defining characteristic of this process—a resulting highly dispersed spatial distribution of settlements in the interior—which goes unquestioned in the historiography. My research thus shifted the discussion from the “discovery” of new regions and the creation of settlements to socioeconomic and cultural mechanisms that promoted mobility, forged connections across space, and enabled long-distance exchanges despite limited geographic knowledge and inexistent infrastructure. In this article, I thus ask how distant portions of the backlands became integrated into the Portuguese empire?

As already argued by many historians, kinship is a big part of this story and family histories, particularly compilations of genealogical data focusing on colonial São Paulo, became invaluable sources of information for researchers interested in the subject. These works provided narratives of explorers journeying the backlands and anecdotes about kinship dynamics and social formation. Yet, a systematic approach to these sources was missing, partially because of the large size of these collections or the “dryness” of the information compiled in them. While a few entries offer a colorful narrative about the life story of specific historical characters, most of the records only list the names, family relationships, and vital information of thousands of these colonists, often as a one-sentence remark. Geography is a central element in this works as the places of birth, marriage, and death are often mentioned, albeit in an incomplete fashion. Using this information combined with a series of digital methods, this article takes a step back from the individual records and anecdotes to reconstitute the geographic mobility inadvertently embedded in these life stories. This approach allowed me to “read” these records in a different fashion, focusing on broad patterns instead of on specific examples, and produce a narrative that places mobility as a vital element of Luso-Brazilian society.

On April 22, 1715, the marriage of Maria de Arruda Leite and João Antunes Maciel was listed laconically in the parish books of Itu, a small town in a frontier zone of colonial Brazil. The recording of the wedding took just a few lines, using a customary template to state the couple’s and parents' names and declare the administration of the holy sacrament of matrimony.1 This formulaic act, repeated thousands of times by priests in the Portuguese empire, reveals a sense of ordinariness that permeated the union. The couple was born into distinguished families that settled in the region during the 17th century, engaging in the exploration of frontier resources. Bride and groom grew up in the same nearby town and, coincidentally, moved with their families to Itu a few years before the wedding. Most likely, they knew each other quite well and the union was a much-awaited event in the community.

The ceremony thus seemed an ordinary happening in the town – to the point that the groom’s absence could pass unnoticed to the modern observer. On that day, João entered into wedlock by a proxy appointed to act in his interest while he journeyed the backlands of South America. Canon law and ecclesiastical regulations provided for the administration of a sacrament in absentia, but this was reserved for extraordinary occasions and required the approval of an archbishop, who lived more than a thousand miles away. The lack of any indication in the marital record makes it unlikely that the couple had an authorization of this sort, yet the union was celebrated normally and confirmed by the birth of three daughters in the following years.

Life stories like this, in which mobility and absence were everyday imperatives, were not uncommon in the fringe of the Portuguese empire. Itu was one of the few towns that the Luso-Brazilian settlers established away from the coast before the 18th century, in a small cluster of inland settlements around São Paulo.2 This geographic setting deviated from a long-standing pattern of Portuguese empire-building. Since the 15th century, settlements established overseas were confined to the littoral and integrated into the empire through maritime routes.3 The one-hundred miles that separated Itu from the nearest port was not overwhelming, but the orientation of these settlements, contrary to the rest of the overseas domains, was towards the vast interior of South America.

Historians associated the geographic mobility of Luso-Brazilians colonists with the frantic rush prompted by the discovery of gold at the turn of the 18th century or as part of the social dynamics of frontier societies. Taking the viewpoint of state actors, to whom mobility was a form of transgression and fiscally damaging, the first group of scholars described itinerant lifestyles as marked by precariousness, marginality, and poverty.4 The large contingent of colonists lured into the backlands composed a picture of chaotic settlement that favored tax evasion, contraband, and social laxness.5 Other scholars, especially those focusing on colonial São Paulo, argued that mobility was a central feature of those communities in the fringes of the empire. Driven by opportunism or lack of alternatives, colonists relied on resources they could exploit in the backlands, such as Indian slaves and land, to survive away imperial centers.6

This article connects these strands of historiography by analyzing the spatial practices of the inhabitants of São Paulo during the interiorization of the Portuguese colonization in Brazil. Based on patterns of geographic mobility reconstituted through digital methods, I argue that these colonists' sustained mobility wove together an otherwise fragmented territory. In faraway regions where infrastructure was lacking and the crown’s grasp was weak, the comings and goings of people like João and Maria linked settlements and afforded long-distance social and economic exchanges. On the one hand, these patterns were less disorderly as previously depicted as family relationships structured the way people journeyed and settled inland – people moved to places associated with their kinsfolk, and families maintained long-term ventures in the same locations for generations. On the other, the consequences of these practices, deeply rooted in the mechanism of social reproduction in the frontier, far exceeded the boundaries of these communities. They not only defined social structure locally, as posited by the second group of historians, but also shaped the geography of the empire in the backlands. This mode of kin-based mobility allowed the occupation of these remote areas and provided a way of remaining connected to the rest of the empire.

By centering on the spatial practices of the inhabitants of São Paulo, I challenge narratives that ascribed territorial formation to the actions of state agents or the exceptionality of exploration or social exclusion. Instead, this concept urges a shift in the focus to everyday acts and routines that acquired meaning in space.7 The routinization of mobility in the interior changed the role of the backlands in the imperial geography. In colonial Brazil, as well as in other parts of the empire, the term sertão – here translated as “backlands” – came to signify the opposite of colonization and designated areas beyond the control of the king of Portugal.8 For the inhabitants of São Paulo, on the contrary, the backlands were not an undistinguished interior but a set of specific locations associated with their family’s trajectories. As their settlements relied on frontier resources, they develop a series of practices that made that environment amenable for exploitation. They partnered with relatives to outfit slave raids or search for minerals, cultivated land plots far away from settlements, forged regional alliances through marital unions, and conducted their lives in several places at once. These colonists also learned techniques of movement and grew accustomed to the isolation of the backlands. In all, as expressed in the story of João and Maria, mobility and absence became ordinary aspects of their lives.

With the discovery of gold deposits in central Brazil at the turn of the 18th century, these colonists repurposed their spatial practices for the occupation of the backlands. Nevertheless, the vastness of the territory contrasted with the small pockets of Luso-Brazilian settlements that dotted the interior. Their capacity to move and remain connected was instrumental to the survival and integration of these new areas of occupation. Notably, the repetition of the journeys between the same locations over time reinforced the ties that bound together distant places, favoring the circulation of information, people, and goods and granting a dispersed geography a sense of cohesion and integration. Kinship-based mobility offered a mechanism to occupy large stretches of dispersed land in a territorial configuration, though inland, remained rather insular. In this sense, the spatial practices developed in the 17th century were extended to a larger geographic scale during the first decades of the following century, creating an intangible infrastructure that impersonated the spatial configuration of the Portuguese empire in the backlands.

This article relies heavily on what has been generically described as “digital methods.” Although the term itself isn’t very descriptive, it serves to indicate that the central evidence supporting this study was systematically produced, analyzed, and represented using computational tools. The research was a multi-step process and required a combination of different tools and techniques. In the process of creating the dataset, I used optical character recognition (OCR) to generate raw data, custom-written Python code to parse and extract information, a front-end web interface for manual revision, and a relational database (MySQL) to organize and store the data. The database format allowed different types of queries, from browsing records of the family of an individual to quantitative analysis. Lastly, GIS mapping was also crucial to analyze and create visualizations that support the argument of the paper.

The term “digital methods” covers all these different steps, the combination of which was the most time-consuming part of the project. Individually, however, each of these parts—except for GIS mapping—was a common way of handling data. (There are some noteworthy insights, though. For example, the computational techniques I used allowed me to “read” a book differently, such as connecting parts of the genealogies that were scattered across the different volumes of the book.) In this sense, they don’t constitute a standalone method. Moreover, their reproducibility is also questionable. While genealogical data is widely available for many places and periods, I used a very specific set of materials that was intimately associated with the research question I was investigating. A detailed account of the process of creating the dataset, which is common in digital humanities articles, thus seemed less important than focus on the historiographical contribution I intended to make.

Therefore, I decided to write this text as a regular historiographical essay and include methodological information sparingly. My rule of thumb was to have the minimal amount of methodological discussion to make my evidence understandable and support my claims. I attempted to inform the reader very briefly about the data I presented and how I was interpreting it. In this sense, the digital methods that I used lie in the background of the text. One of the consequences of this was that hard-to-produce data might seem deceptively trivial in some cases. When I make a statement like “X descendants of an explorer ended up settling in the place he discovered,” the amount of work and tinkering to produce that small bit of information is obscured. Often, it required a lot of fiddling with the dataset to find the best records to make a point.

However, the hardest part to communicate is how the practice of making digital history deeply informed the understanding of the research object and shaped the argument of the article. Building this dataset was a way of thinking through the source materials. This process not only produced analyzable data but also offered an environment and tools to “play” with it. It was like taking apart and rebuilding, in a novel and purposeful way, a toy: by disassembling these texts and reassembling them digitally, I transformed my understanding of its content and structure. For example, the idea of a pattern of multi-generational circular mobility—“returnees” moving to places where previous generations of the family were settled—came after revising dozens of records in which siblings married in their parent’s hometown. It wasn’t a prior hypothesis tested through quantification, but an argument developed through the painstaking work of handling the dataset. They were the results of the experience of working with genealogical writings through various digital methods.

This article is the result of a novel way of reading traditional sources using digital methods. For generations, genealogists have recorded information about the lives of the inhabitants of São Paulo. Most of the writings were sparse, usually focusing on the genealogists' family history, but three comprehensive efforts to record the lineages of São Paulo have been published in the past two centuries.9 These writings weave together individual vignettes – in most cases, just a few lines containing the known dates and places of birth, marriage, and death – within the set of familial relationships. Assisted by digital methods, I analyzed these records collectively to delineate intertwined patterns of geographic mobility and kinship formation and understand the meaning and motivations underlying these spatial practices.10

Genealogical compilations about the lineages of Luso-Brazilian colonists in São Paulo have existed since the late eighteenth century when Pedro Taques de Almeida Paes Leme—whose short biography appears towards the end of the article—began to gather information about his fellow countrypeople. Since then, several genealogists revised, corrected, and expanded his early writings, publishing new versions of the compilation. In 2002, genealogist Marta Amato revised and re-published the most important of these compilations (the Genealogia Paulistana), which is the basis for this study.

This edition includes more than 70,000 individual entries arranged in a descending numbering system that replicates family relationships, starting from a progenitor (an “original” settler). I identified 28,849 entries that were relative to people living during the colonial era, which represents a sizeable share of the total population. For example, in 1687, while ecclesiastical authorities counted 15,400 parishioners in the captaincy of São Paulo, the dataset listed 2,848 individuals (18.5%). Gender distribution slightly favors women (1:0.97 female-to-male ratio), but their records were usually shorter than their men’s. We can also assume that, due to the nature of the genealogical enterprise, the upper sector of São Paulo society is overrepresented in the dataset.

Although the dataset is relatively large, it is very sparse and fragmentary as most records had very little information. However, because datapoints are linked through family relationships, I could augment and enhance it in two ways. First, I used siblings' data to identify the period in which a person lived (based on large temporal units of 50 years,) which made useable records that didn’t include dates. Second, I also connected families that, because of the linear structure of the text, were in different parts of the text. (For instance, family A has a record of X marrying Y, and family B has another one of Y marrying X.) This procedure allowed me to observe the importance of in-laws, as already pointed out by the historiography, in the marriage strategies of this population.

From the subset of colonial-era individuals, I located 2,948 records that listed places of birth and marriage. Inspired by origin-destination analysis, which infers geographic mobility based on origin and endpoints of a journey, I used these datapoints to trace the spatial practices of these colonists. Figures 3 to 5 summarize the results. In addition, other selections of the dataset, including places of death, complemented the study.

This material became a relational database containing around 30,000 entries about individuals who lived in São Paulo or its area of expansion between the 16th and 18th centuries. The textual records were parsed to extract information about the individuals' lives while the textual structure of the genealogies, which reproduced family relationships, was preserved in the digital medium. The transformation of these writings into networked data removed the linearity imposed by the text, allowing the recombination of the web of family ties. Individual stories of wayfaring and mobility were read alongside those of siblings, cousins, in-laws, and other relatives that helped define where people ended up settling and carrying on with their lives. Moreover, linked data also helped to mitigate the constraints of an extraordinarily fragmentary and incomplete corpus. From the universe of individuals included in the genealogies, I identified more than 3,000 people with multiples mentions of being in a particular place, from which I based most of my analysis.

Feedback I frequently received in writing this article, including from one of the reviewers, was to include a “simple map” giving an overview of the studied areas and showing the places I mentioned in the text. As it is a common practice among historians, especially those that don’t focus on “central” places – nobody asks for a map to show where Paris is – the absence of such a map causes discomfort and disorientation among the readers.

Not having this simple map was an intentional choice for several reasons. My work attempts to understand how space is historically produced and, thus, liable to changes over time and explainable through temporal analysis. Giving a static representation of this space, especially when the article covers a long period, would contradict this conceptual framework. It would also mislead the reader to believe that a well-ordered space actually existed. The choice of not including such a map is also supported by debates on information design and among historians who use visualizations, which assert that visualization should further arguments. That is, visualizations articulate a set of evidence to demonstrate something to the reader. A “simple map” – which would offer a stagnant depiction of colonial Brazil – would undermine the article’s argument.

The use of a basic map also raises issues specific to my research. First, it would ascribe a top-down, grided territoriality that was alien to the historical agents discussed in the article. A seventeenth-century Luso-Brazilian colonist had a very different perception of space than the aerial view of a modern map. Second, that map would emphasize the linear distance between settlements as a central explanatory variable. Indeed, distance, especially when measured using contemporary standards (such as day’s travel instead of miles), are an essential piece of any analysis that centers on space. However, the underlying argument of the paper is that for the mobility of the inhabitants of São Paulo, the distance or availability of infrastructure mattered less than the social relation and kinship networks established across locations.

Still, the discomfort caused by this absence remains, and I took two measures to mitigate the disorientation of the readers. First, I tried to distill the information that would exist in the basic map into the existing visualizations. Second, in the revised version, I opted to openly confront this problem. I make explicit the choice of not having the map and use that as an opportunity to discuss the theoretical underpinnings of my work and how they manifest in the structure and choices of the article.

This approach allowed observing broad patterns of mobility, recombining the data in multiple ways, and delving into specific exemplary cases. Furthermore, visualizations, particularly maps, were key in this investigation. They not only summarize selections of data but graphically represent the argument put forth in the article.11 The maps I present here are not merely devices for spatial orientation, such as traditional “base maps” that preface books and articles of this sort. Instead, I purposely avoided a base map to “show where things are.” They flatten the agents' historical experience by imposing an aerial, omniscient view of space and contradict the main tenet of the article – that space is produced historically. Instead, I opted to produce visualizations only with data for the period in question, incorporating relevant information for orientation in the existing maps.

A Society on the Move

By the time of its foundation in the mid-16th century, São Paulo was the only Portuguese town in the Americas away from the Atlantic Ocean, contrasting with a century-old pattern of empire-building. For most of the early modern era, the Portuguese presence overseas was limited to coastal settlements spread across the globe but connected to the empire’s center, Lisbon, through maritime routes.12 In South America, the physical and human geography encouraged a sharp separation between coast and backlands. The Serra do Mar, a system of mountains that stretches for more than 1,000 miles along the coast between latitudes 20o and 26o S, hindered the access to the interior with peaks that could reach 7,000 feet and were covered by lush tropical rainforest. At the same time, they delineated a long but thin strip of land easily accessible to colonists.13 This dichotomy also marked European perceptions of the human geography. While the Portuguese mostly encountered a relatively homogenous linguistic group, the Tupi, along the coast, the interior was populated by the “ferocious” Tapuia – a generic designation for non-Tupi people.14

Initially, the empire’s extent in South America barely stretched a few miles away from the sea. In the words of friar Vicente de Salvador, the Portuguese, “although great conquerors of lands, do not take advantage of them but are content to move along the seacoast scratching at them like crabs."15 The foundation of São Paulo, an inland a dozen miles to the west of the Serra do Mar, deviated from this mode of spatial organization. It was located two or three days away from the nearest port through a steep and poorly maintained trail – a “tyrannical march,” as described in the 18th century.16 The settlement began as a Jesuit venture to assemble and convert Indians, but soon after its creation, it received a contingent of Luso-Brazilian colonists and their Indian allies. Over the next two centuries, São Paulo became a thriving regional center.

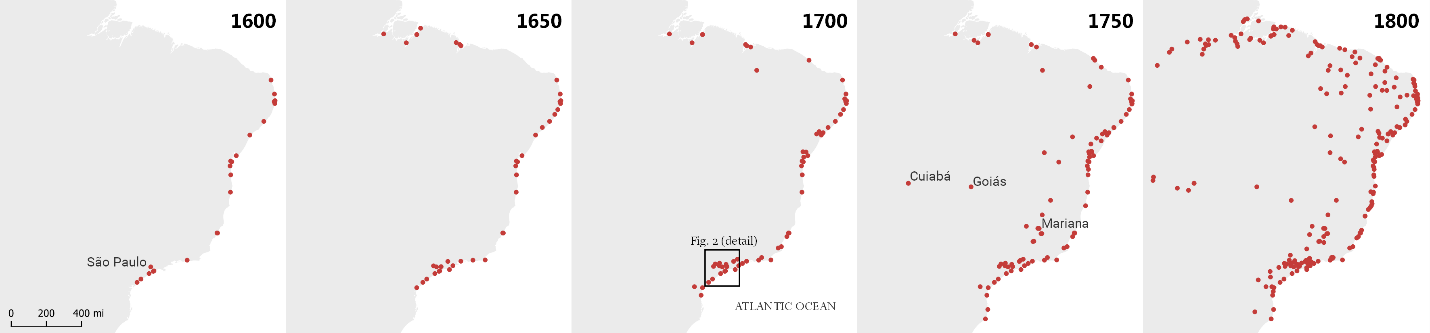

This visualization gives a brief overview of the process of territorial expansion of the Portuguese colonization in Brazil. Because I used a comprehensive dataset of towns and cities, it included many places that weren’t part of my narrative. They could mislead the reader, though. For example, what appears to be the most dynamic area of expansion – the string-like network of new towns along the Amazon river in the second half of the 18th century – isn’t centrally related to the process I’m describing. (For an excellent analysis of this subject, see Heather Roller’s Amazonian Routes.) Instead of arbitrarily selecting points that would demonstrate my argument, I indicate in the captions those aspects I wanted to emphasize in the visualizations and then discuss them in the text. This is becoming standard practice in DH articles, although many readers still just skim through the images and captions.

Figure 1.

Location of Portuguese towns (vilas) and cities (cidades) in South America. Several smaller settlements (mining camps, parishes, chapels, ranches, outposts, mining fields, etc.) existed alongside these cities and towns and, very often, several miles away from any major settlement. Data from Tiago Gil et al. “Vilas e Cidades” Atlas Digital da América Portuguesa. Brasilia: LHS/UnB, 2017. http://lhs.unb.br/atlas. Accessed January 4, 2019.

The location of the town was unique compared to other settlements. As a colonial governor recollected, São Paulo “was in the edges of a slightly inclined circular plateau and rules over, in one direction, as far as the sight could reach and, on the other, the multitude of gigantic mountains that form the horizon."17 This stark contrast between an impeding topography and an inviting flatland favored the engagement of the inhabitants of colonial São Paulo with the interior. Nevertheless, this process relied on spatial practices adequate to the exploitation of the backlands. As an unknown set of environs, South America’s interior posed challenges that were slowly overcome by the people in the fringes of the empire. By venturing the interior in search of land and labor throughout the 17th century, Luso Brazilians living far from the center of the empire grew accustomed to the harshness of these environments.

First, the highlands of São Paulo presented colonists with an abundant supply of land, which was exploited through indigenous techniques of cultivation known as coivara or roça-de-toco – and, in modern times, slash-and-burn, swidden, and itinerant agriculture. This farming technique was based on the use of fire to clear tracts of forest and fertilize the terrain. Initially, the land was very productive, but yields plummeted after three or four seasons, forcing planters to find locations with dense vegetation and restart the process.18 As they moved further into the backlands, these colonists also extended the area of Portuguese occupation. Farming grounds were often located several miles away from urban centers, and colonists had to spend most of their time interned in remote areas. Eventually, as suggested by Sergio Buarque de Holanda, this spatial dynamic triggered the creation of new urban cores as planters became too distant from their hometowns. When that happened, settlers gathered together to found a new village, organize their institutional apparatus, and resume religious services and social life.

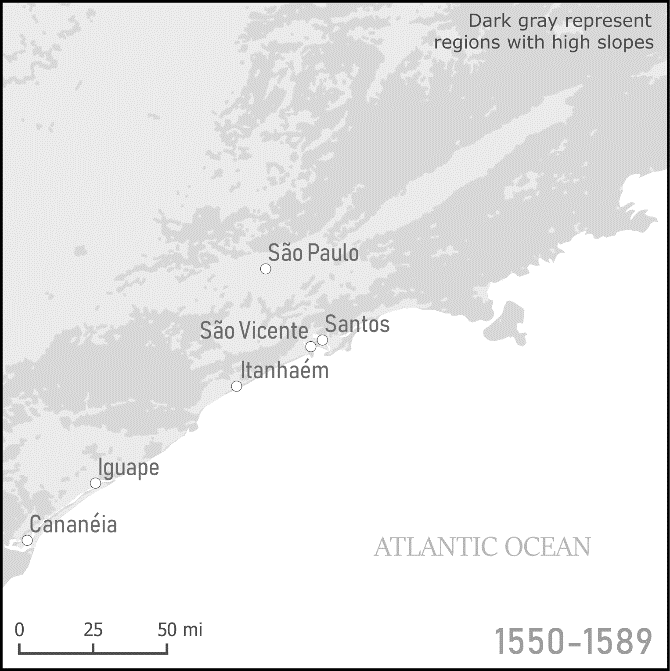

During the 17th century, nine inland towns and three coastal ones were created in the captaincy of São Vicente. They remained small, as the creation of new settlements meant a demographic decline in former towns. However, this process allowed the empire to extend itself to a large area in the interior even with meager population growth.19

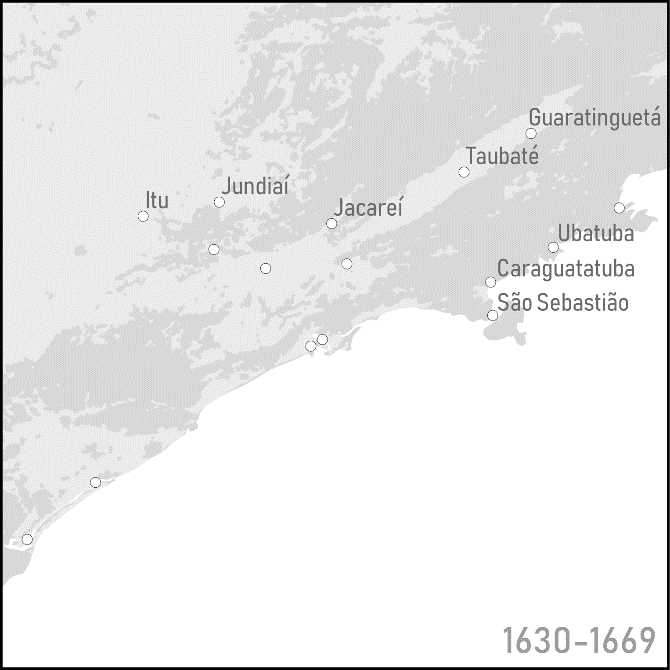

Towns created in the captaincy of São Vicente between 1550 and 1710. These maps show two expanding frontiers. First, the towns of Parnaíba, Jundiaí, Itu, and Sorocaba followed the Tiete River westward, marking a vital route to access the central regions in South America. Second, colonists also populated the valley of the Paraíba River, creating the towns of Jacareí, Taubaté, Guaratinguetá, and Pindamonhagaba. In the second half of the 17th century, this string-like network of towns pointed colonists to the Cataguazes region, around 100 miles northeast. In these maps, labels appear only in towns created in the frame’s timespan. Dark gray represents areas with hilly topography.

Figure 2.

Labor was also a product of the frontier. Despite legal restrictions imposed by the crown, the inhabitants of São Paulo relied heavily on Indian slaves to compose a workforce. They toiled the land, worked as servants and in a broad array of menial jobs, participated in warfare, and had a pivotal role, as carriers, in sustaining the commercial links the coast. Early on, missionaries undertook efforts to control native labor by creating mission villages (aldeamentos) in the highlands. They assembled indigenous populations that lived dispersed and rented their work to Luso-Brazilian colonists through contract labor. However, this model failed to provide a stable solution for the emerging settlements, and colonists took upon themselves the task of producing a workforce. 20 They thus began to outfit expeditions, known as bandeiras and armações, to enter the backlands and enslave indigenous peoples. Initially, these raids centered around São Paulo, but, with the dwindling population close to the colonial settlements, expeditions increased the distances they traveled to find their prey.

The organization of these expeditions was largely a family activity. Relatives, friends, and allies partnered to raise funds, gather resources, exchange geographic information, and reassign Indians in their possession to act as guides and porters.21 Since capital investments were low – explorers packed just a few items such as firearms, gunpowder, and hammocks, and lived from what they gathered and hunted – the most valued resource was experienced Luso-Brazilian men who could join these enterprises. Families invested heavily to increase the number of people that could contribute to these expeditions. Male children accompanied their fathers and relatives in the backlands as part of their training and coming of age, hoping that they would learn the techniques and knowledge necessary to survive in the backlands and eventually lead expeditions on their own.22 Moreover, Portuguese inheritance laws, which mandated the equal distribution of the deceased’s property among children and thus created a tendency of downward mobility, also contributed to increasing the pressure over the offspring to adventure the interior and incorporate new resources into the family’s pool. Lastly, relatives who stayed, including women, also supported these expeditions by taking care of the family’s business during the absence of the travelers or by helping the parties from afar.

In a rare glimpse of the daily affairs of one of these expeditions, when a participant died and left the inventory of his property, it is possible to see the extensive, if not convoluted, way in which kinship made wayfaring possible. On June 28, 1645, a fatally ill explorer, Antonio Gomes Borba, summoned his colleague Francisco Bicudo Fernandes to write his will. Borba lived in the frontier town of Santana do Parnaíba with his wife and daughter, but his surname was a constant reminder of his birthplace in Portugal. It is unclear when he moved to Brazil, but it is certain that, once there, he strove to forge alliances with local families that eventually led him to be part of that expedition. The choices Borba made on his deathbed (or death-hammock) reveal the strength of these relationships. He appointed Antônio Pedroso de Alvarenga, his companion in the expeditions, as the curator of his daughter’s property. In fact, Alvarenga was already the godfather of Borba’s daughter, and both men were long-standing business partners. As noted in the will, the only debtor that the wounded Portuguese men remembered was Alvarenga’s father, who owed Borba 4.5 tons of wheat.

After Borba’s death, the personal belongings he had brought to the backlands were auctioned among the members of the expedition, revealing the names of other participants. In fact, Borba represented the end of the chain of familial relationships – in his case, through the fictional though nonetheless indispensable spiritual kinship through godparentage – that sustained that armação. Borba’s closest allies, the Alvarengas, probably helped him to breach the social fabric of the highlands of São Paulo, granting him access to a larger pool of potential partners. Not only was the younger Alvarenga related through a marital alliance to the will’s scribe, but two of his brothers-in-law (João and Antônio Bicudo de Brito) appeared among the members of the expedition as well. A fourth cousin-in-law, Cristovão Aguiar Girão, also accompanied them into the backlands. Besides the relationships reconstituted through the genealogical data, the other two members of the expedition shared the surnames of the other party members and, most likely, were young men wayfaring together with their kinsfolk. Girão, for instance, was the guarantor of a certain Manoel Girão in the auction. Lastly, one of the leaders of the expedition, Captain Francisco Siqueira, was related to this group through marriage – he was the stepfather of the writer of the will.

In all, this kin group included nine of the fifteen participants listed in Borba’s probate inventory. Besides Indians, who were silenced in this documentation, there were probably other Luso-Brazilians in the expedition, but the number of names listed in the record matches the average size of a small expedition.23 Little is known about the other names that appear on the list. Even the expedition leader, João Mendes Geraldo, did not receive extensive attention in the genealogical records, besides the fact that he brought along his son, Miguel Gonçalves Correia, to the backlands. Neither do we know about the destination of the expedition. Most likely, they were headed to the sertão of the Paraná River, where two of the party members had visited on previous expeditions: Cristovão de Aguiar Girão visited the region in 1638 and Francisco de Siqueira in 1641.24

The prevalence of in-laws journeying the backlands together also exemplifies the role of marital alliances in forging these partnerships and fostering mobility. In fact, the sizable dowries that the families of São Paulo reserved for their daughters, as demonstrated by Nazzari, were an attempt to recruit sons-in-law for the pool of specialized labor. Parents significantly favored their daughters in disposing of property, as dowries, considered an advance inheritance, far exceeded the sons' share in the bequests. By doing so, parents expected that their daughters' family would be able to set up a new production unit, and her in-laws would become a potential partner for the slave raids in the backlands.25

Interestingly, these marriages increased the sense of spatial cohesion among the dispersed constellation of little towns in the highlands of São Paulo. The small number of potential local spouses and the high premium in finding a good match provided incentives to single men and women to extend their spousal search outside town. The settlements around São Paulo had, at best, only a few thousand residents and did not offer many options of spouses that matched social and racial status, kinship restrictions, and affinity. However, if willing to search for a husband within a day-long horseback ride (~30 mi), a single woman would double the number of unmarried males and potential spouses; the increase was threefold after two days of travel. Furthermore, searching for spouses elsewhere would offer other advantages. Besides enabling access to resources locally bound to other towns, such as fresh tracts of land, marriages established with outside residents increased the alliances and potential partnerships that a family could forge.26

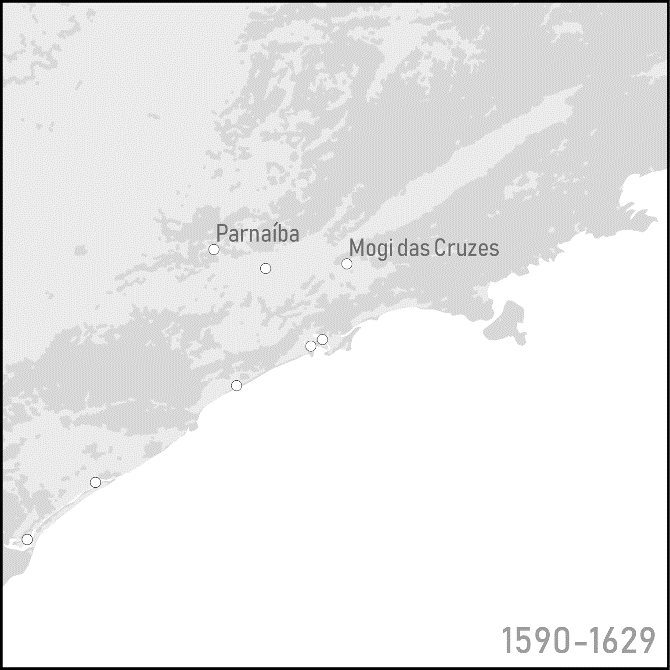

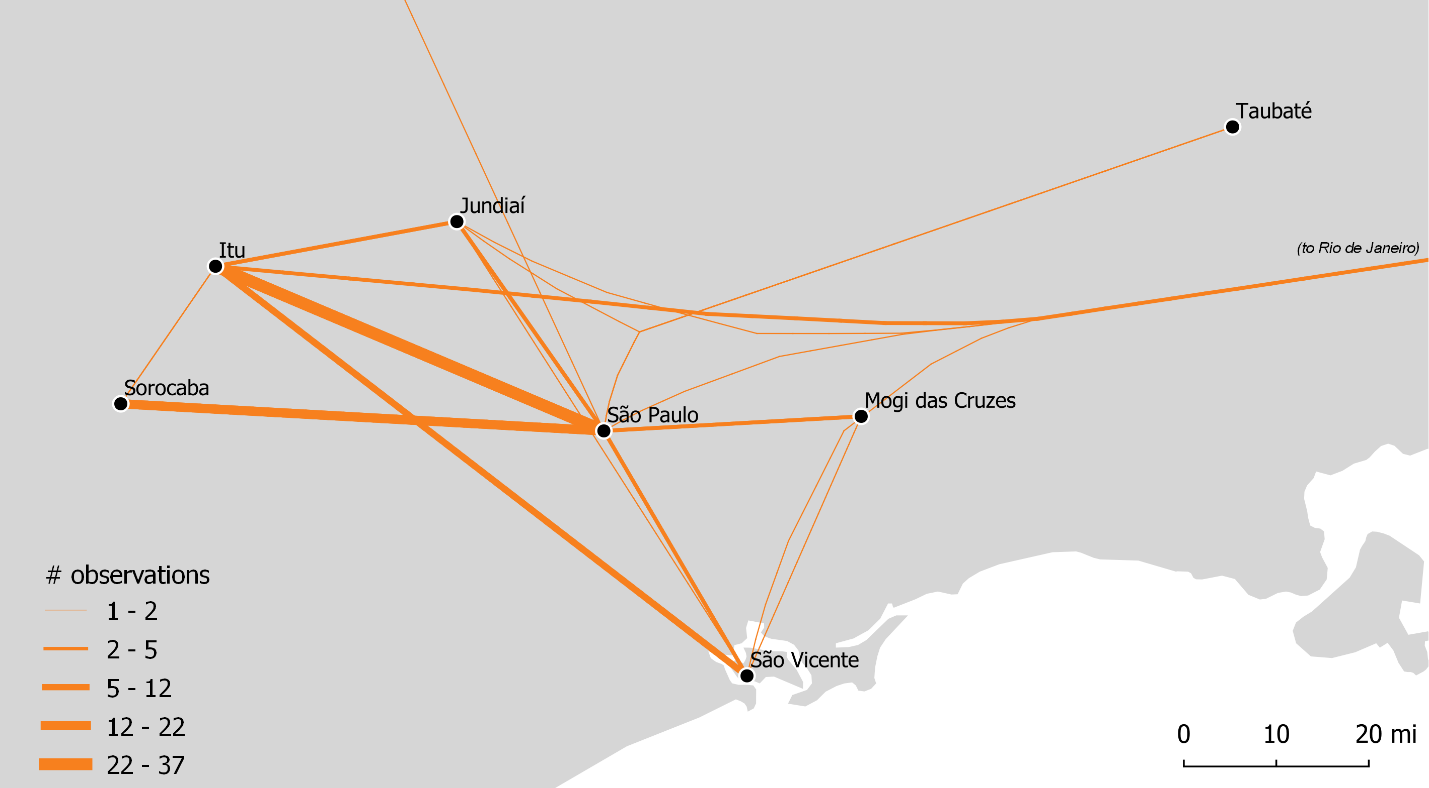

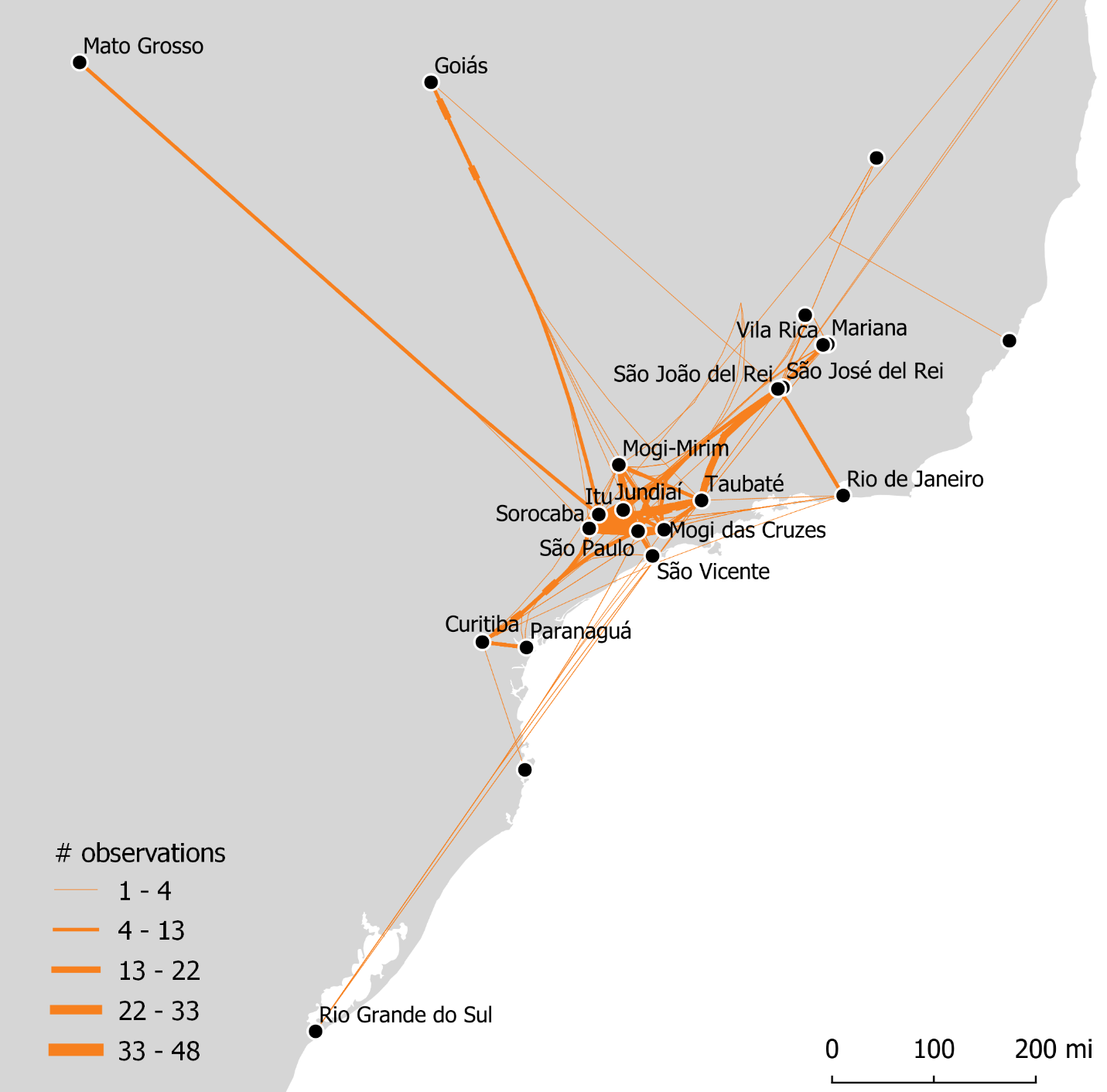

Figure 3.

Spatial trajectories of spouses in the second half of the 17th century, based on places of birth and marriage. Line thickness represents the number of people that made the journey between two towns and, therefore, the strength of the connections forged by families established in different locations. To avoid over-fragmentation of the data, nearby towns – like those that appear in Figures 1 and 2 – are grouped in micro-regions named after the most important town. Lines are ‘bundled’ based on Anita Graser et al., ‘Untangling Origin-Destination Flows in Geographic Information Systems,’ Information Visualization 18, no. 1 (January 2019): 153–7.

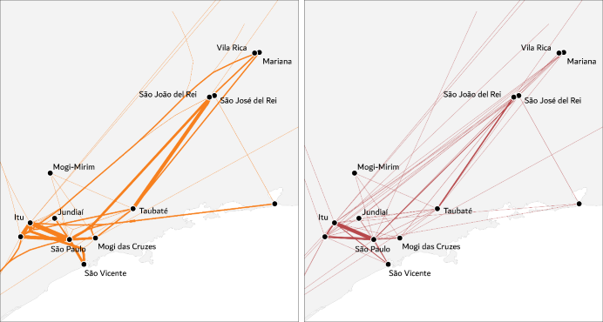

I used this edge-bundling technique to make the visualization more readable and “abstract,” in the sense that it highlights underlying patterns in the data that are not apprehended from a single data point. Edge bundling aims to reduce visual clutter by grouping (and deforming) similar edges. In this case, the technique also helped to emphasize connections between different regions (as the edges were bundled at a regional scale) instead of between discrete locations. The following maps compare the same dataset with (left) and without (right) bundled edges:

The strength of this method is to aggregate data and reveal broad patterns (at the expense of the granularity of the data.) Because the data is very dispersed (as visible in the many thin lines in the map on the right), I opted to incorporate the presentation of data subsets in the relevant sections of the text, but the focus remained on the overall trends. Therefore, visualizations express general patterns and the text discusses certain inter-regional connections to illustrate how they functioned.

Genealogical data for the second half of the 17th century illustrates this strategy of expanding the radius of the spousal search. Figure 3 indicates the dislocation between the place of birth and wedding (n=135) and reveals the preference for partners born outside town. For spouses born and married in the captaincy of São Vicente (115), 60% married outside their birthplace, while the remainder preferred to find spouses locally. In older towns, such as São Vicente, São Paulo, and Mogi das Cruzes, the ratio of local-to-regional marriages was less than 1 – that is, more people married outside, in a nearby town – while there is a clear preference for local matches in newer towns. There, local marriages were at least twice (Itu) or three times (Sorocaba) as common as regional ones, reinforcing the argument about the interest of these colonists in the frontier zones. Older urban cores had potentially less land available and thus exercised pressure for mobility; newer zones of colonization unlocked unexplored pools of resources – and moving there increased their ability to exploit them.

Marriages outside the captaincy, possibly because of the geographic coverage of the dataset, were rather infrequent (3 cases), whereas the number of Portuguese immigrants marrying local women was significant but still small (18 cases.) Interestingly, access to frontier resources to these newcomers seemed to be hindered by their lack of local connections as they settled in more consolidated cores. Most Portuguese men (including two from the Azores) married in São Paulo or the coastal town of São Vicente, while only two of them managed to find spouses inland, in Itu. The data is also unclear about when the movement happened – in other words, if the mismatch between the place of birth and marriage occurred before or was related to the union. Nevertheless, the significant proportion of people marrying outside their hometowns offers strong evidence that these restricted marriage markets helped to foster mobility in the spatially dispersed urban network of the highlands of São Paulo.

The consequence of the pattern of family-related mobility was that, although the geographic extent of settlement increased rapidly, the small urban enclaves remained socially connected among themselves and, through frail links with the littoral, to the rest of the empire. In this sense, the alliances forged through marriage weaved through the discontinuous space in the highlands of São Paulo. While living in the remoteness of their farms, ranches, and small villages, colonists produced enduring ties with people in similar isolated circumstances. In this sense, moving to the interior was not an act of leaving their social world behind. On the contrary, it meant extending the Portuguese colonization to a new region where, through these family links, colonists reproduced their mode of living despite the weak grasp of the Portuguese monarchy. These kinship networks guaranteed a cohesive and densely linked social space.

The needs for fertile land, enslaved native labor, or spouses made the inhabitants of São Paulo a distinctively mobile social group. They grew accustomed to life in the isolation of the backlands, in their farms and away from the urban cores; learned to travel long distances and survive in the harsh environment of the backlands; and developed social practices that, even in a sparsely populated region, granted spatial cohesion and belonging to the empire. Nevertheless, the geographic extent of the Portuguese occupation remained limited to the towns neighboring São Paulo, and its enlargement did not mean significant demographic growth. Although the expansion of agriculture gradually claimed more land for the king of Portugal, long-distance expeditions resulted in a process of depopulation of the backlands. The spread of diseases, warfare, disruption of communities, and forced relocation to Portuguese settlements sharply reduced the size of indigenous groups living in the interior of the continent.27

The Portuguese Occupation of the Backlands

The spatial practices that the inhabitants of São Paulo developed during the 17th century acquired distinctive meanings after the discovery of rich mineral deposits in central Brazil. Expeditions departing from the inland towns of the captaincy spotted several gold strikes in the interior during the 1690s, and the settling of these areas followed rapidly. These discoveries were intimately related to the wayfaring of the people of São Paulo, who redeployed their knowledge and experience in journeying the vast interior of South America to fulfill the long-standing hopes of uncovering mineral treasuries. Moreover, the mode of spatial organization of the settlements that were created in these remote areas resembled that of the constellation of small towns in the highlands of São Paulo. Social ties, such as those established through marital alliances, remained spatially dispersed, facilitating economic transactions, information exchange, spread of Portuguese institutions, and cultural assimilation – despite the gargantuan distances that set settlements apart. On the one hand, to a broad sector of São Paulo’s society, the mobility of relatives increased the access to the resources of the backlands (now including mineral wealth); on the other, it helped to consolidate the Portuguese occupation and extension of the empire to these remote areas.

The leading role of the inhabitants of São Paulo in mineral prospecting came about with the confluence of the growing knowledge about the backlands and the recognition by imperial administrators of this vocation. Simultaneously to their wayfaring in the 17th century, the monarchy commissioned explorers to search for precious minerals that were believed to be hidden in the heartlands of the continent. Gold strikes were eventually found along some rivers, but the proceedings were below the expectations and the overall enterprise was considered a tremendous debacle.28 The sense of disappointment was so huge that a governor, when commissioned to this task, replied to his superior that “even though he was put in charge of the examination and inspection of the gold and silver mines of Paranaguá, Itabaiana, and Serra de Sabarabuçu, he would not go on this commission, because it was already collapsing and therefore he had not made any progress."29

The frustration with the consecutive failures of crown-appointed explorers made the crown call upon the people of São Paulo. While cynical about his own chances of finding minerals, the governor provided an alternative in a report he read in the Overseas Council. It suggested that the inhabitants of São Paulo “should be the righteous discoverers of the treasuries that nature and fortune deposited most appropriately in the lands they first settled.” Not only did they have the right, but also the skills, experience, and ingenuity required to carry on this enterprise, argued the governor. 30 Despite their negative reputation, these imperial subjects had been summoned on a few occasions to support the empire in enterprises related to the backlands. Troops from São Paulo had joined the fight against the Dutch and the backlands of Angola as well as had a pivotal role in the destruction of the Quilombo dos Palmares, a community of fugitive slaves in the northeast’s interior. Over time, terms like mamelucos, paulistas, sertanejos, and sertanistas, used to describe the population of São Paulo, became synonyms for wayfaring the backlands.31

In fact, the idea of calling these subjects to the task of uncovering mineral wealth materialized even before the governor offered his opinion in Lisbon. Families from São Paulo were already supporting crown explorers and prospecting expeditions with stores, Indian slaves, and information, but, after receiving a series of royal letters in the 1670s, they took a more active attitude in mineral prospecting. In these letters, the king assured, as existing legislation already mandated, an extensive series of privileges such as nobility titles, gifts, pensions, and royal favor to the discoverers of the mines in Brazil, prompting several of these sertanejos to repurpose their journeys in the backlands to conduct mineral prospecting. The most notorious attempt was led by veteran slaver Fernão Dias Paes. He spent many years in the Cataguazes region in the late 1670s, supposedly finding emeralds (which turned out to be semi-precious tourmalines), but his death in the backlands at the age of 73 abbreviated these efforts. Other expeditions followed, including one led by crown explorer D. Rodrigo de Castel-Blanco in 1681, which counted with the participation of local residents. Yet conclusive evidence of mineral deposits was only reported in the late 1690s.32

Although mineral prospecting intensified in the late 17th century and slavers gradually turned into prospectors and miners, the mode of journeying the backlands remained the same. The socioeconomic organization of the prospecting expeditions still relied on relatives to raise resources and recruit qualified explorers, and the techniques of moving and surviving in the backlands resembled those of the older generation of sertanejos. Most important, the repertoire of geographical knowledge and travel itineraries developed over a century of wanderings and nurtured within family informed the steps taken by these explorers. Kinsfolk revisited regions where relatives traveled to enslave Indians, now with a different purpose. In this sense, the inhabitants of São Paulo redeployed the spatial practices when they saw the opportunity, under assurances of the crown, to reap the benefits of mining in Brazil.

Unsurprisingly, the region where the first gold strikes were spotted has been the object of interest of the inhabitants of São Paulo since the mid-17th century. The Cataguazes region, which gained its name from an Indian group that inhabited the area, was associated with the long-standing indigenous myth of the Sabarabuçu mountain, reputed as the Brazilian Eldorado.33 Besides this marvelous geography, the dynamics imposed by slash-and-burn agriculture and the craving for Indians slaves stirred the people of São Paulo in that direction. As they extended the farmable area over the Atlantic rainforest to compensate for the exhausted farmland, they reached the valley of the Paraíba River (on the edges of the Cataguazes) around the 1640s, leading to the foundation of the town of Taubaté. In the following decades, the area between the Serra do Mar and the Serra da Mantiqueira, a stretch of land approximately 100 miles long and 10 miles wide, saw the creation of two other towns – Guaratinguetá (1651) and Pindamonhangaba (1705) – with the older urban core of Taubaté becoming almost as large as the town of São Paulo by the end of the century.34 Around the same period, slaving expeditions started to focus on that valley and adjacent regions. In fact, with the relocation of the Jesuit mission further south in Spanish territory, the Cataguazes became the preferred region for slave raids, and at least 30 different expeditions journeyed the area (around half of all expeditions listed by Monteiro for the second half of the 17th century.)35

The geographical knowledge produced through traveling the backlands and shared among kinsfolk was crucial for the success of prospecting enterprises. For example, the itinerary that led to one of the first discoveries, spearheaded by Bartolomeu Bueno da Siqueira in 1697, was given by his brother-in-law Antônio Rodrigues Arzão.36 Moreover, although he established the route in the years preceding his death in 1696, Arzão was probably very familiar with the region as his father and an uncle led expeditions there in 1662 and 1679.37 In a similar vein, the unsuccessful expedition of Fernão Dias Paes was resumed by his son Garcia. He was already in charge of the returning party after the death of his father, but, after arriving in São Paulo, Garcia outfitted a new expedition to return to the same area. There, his uncle awaited with equipment and subsistence plots. In the early 18th century, Garcia traveled to the region again, now under the auspices of the governor-general of Brazil, to open a road between the mining region and Rio de Janeiro.38

Family knowledge was also crucial for mineral discoveries in other regions of central Brazil. In 1720, a partnership of three veteran sertanejos – a father-in-law with a son-in-law and his brother – organized an expedition to Goiás, which was justified on the grounds that the expedition leader “was familiar for have already wandered the backlands of the Americas in expeditions they have done.” 39 When he was a 12-year-old boy, Bartolomeu joined his namesake father in a slaving raid against the Goiá people, acquiring extensive knowledge about the human geography of the region, as attested by the comprehensive listing of ethnic groups in the petition to the captaincy governor. With official approval, they outfitted an expedition that spent three years exploring the region until they found plentiful gold strikes.

Similarly, kinship networks also paved the way for the occupation of these areas. For instance, the members of the expedition led by Siqueira, as recollected by an early settler, “after finding gold in significant amounts, sowed new plots and sent out for their relatives and friends in São Paulo and nearby towns to come there and establish themselves."40 The expedition to Goiás probably functioned in the same way, as the genealogical records show that several relatives of the expedition leaders ended up settling in the region. From the son-in-law’s side, whose extended family lived in the coastal town of São Sebastião, at least six people (among their and their siblings' children) migrated to Goiás during their lives. In the next generation of the family, three grandchildren (whose parents did not migrate) also moved there.

The transformation of slavers into miners also favored more permanent forms of settlement and territorialization. Besides the creation of new towns in the manner and style of Portuguese legislation, requests for land grants (sesmarias) had a pivotal role in laying out an institutional ground for the extension of the Portuguese empire in the backlands. Again, the wayfaring of relatives informed where colonists claimed these new tracts of land. For instance, in the 1720s and 1730s, Luis Pedroso de Barros and his brother requested a few plots in the headwaters of the Paranapanema River, a couple hundred miles southward of São Paulo, precisely in the region where his father-in-law discovered placer gold in the late 17th century. The petitions used several toponyms, including the indigenous names of rivers in the Paranapanema watershed, revealing their extensive knowledge about the region’s physical geography.41

Land claiming also took the form of a family enterprise, as suggested by the strategies adopted by Luis' kin. In 1704, a coalition of 26 supplicants led by his uncle, Pedro Taques de Almeida (with his children, siblings, and in-laws), requested an enormous land grant of 900,000 hectares (2.2 million acres) in the region next to his nephew’s properties. (The extended family filed another petition, almost identical in its form, dimensions, and claimants, but requesting land in the Minas Gerais region.) The artifice of enlisting the entire family to justify the enormous proportions of the grants did not persuade the governor, who only approved the standard 2,000 hectares (5,000 acres) plots for the family.42 The temporary setback did not inhibit the family’s ambitions. In the following years, family members requested, individually or in small groups, several other plots in the lands adjacent to the first concession. By the 1720s, the family held more than 30 land grants in the region, almost recreating the extent of the original request.43 Besides incorporating these lands through judicial instruments recognized by the empire, these requests registered for the first time the names of faraway, unheard-of places in the records of the bureaucracy of the empire.

Land ownership did not diminish the mobility of the people of São Paulo. In fact, the survival of settlements created in the backlands depended on the continual exchanges that the flow of people afforded, and several of the families of first settlers kept property, businesses, agents, and political and social relations spread between distant locations. The land grants requested by the Taques de Almeida family, for instance, were used to create ranches, which were managed through an agent.44 On these properties, the clan raised livestock that was sold in the interior of São Paulo and in mining areas, where the family kept a flourishing commercial enterprise.45 Eventually, two young members of the family moved to the region and married into the local elite, reinforcing the ties that the clan forged with this distant district.

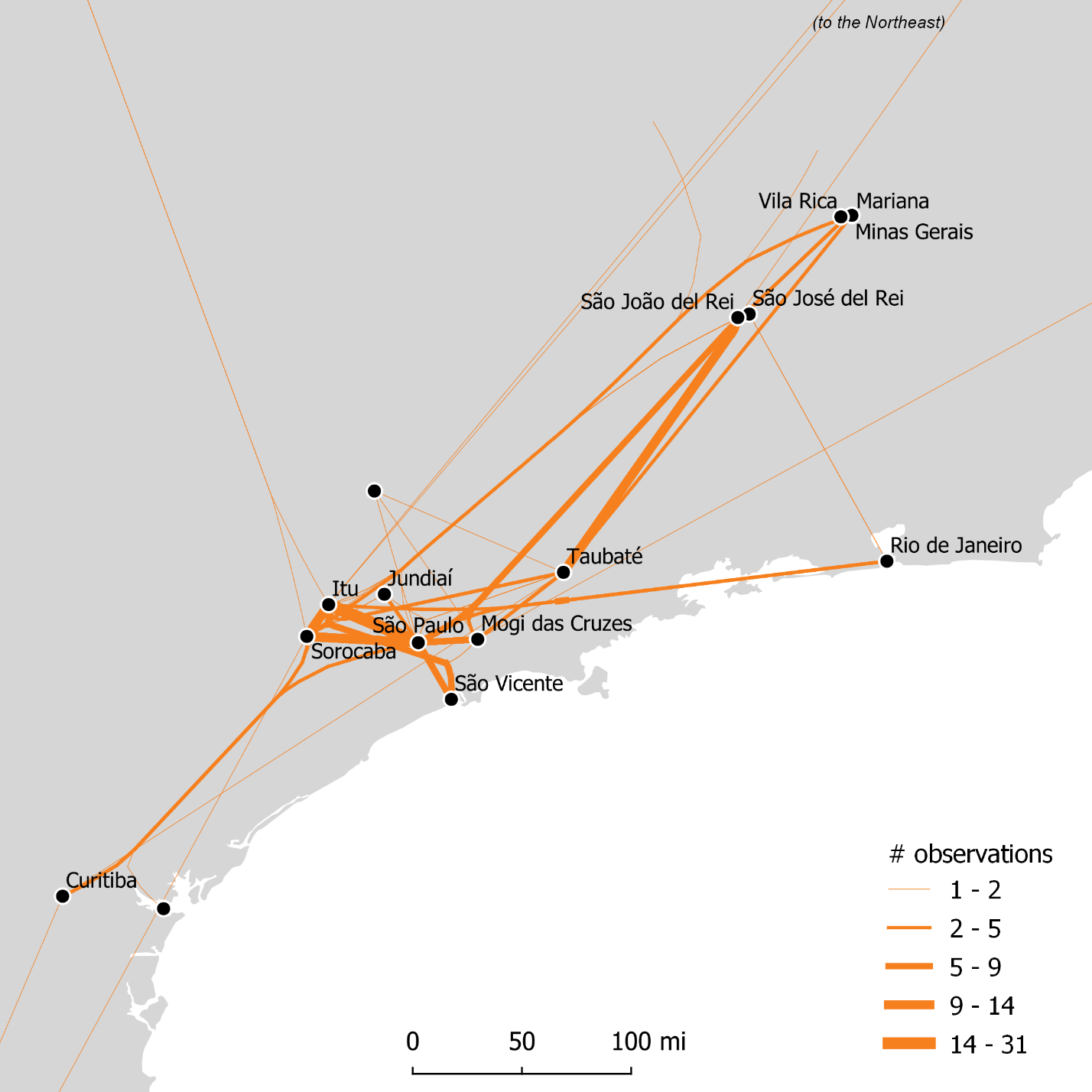

In the years following the discovery of minerals, several inhabitants of São Paulo relocated to the expanding zones of the Portuguese occupation. The dislocation between birth and marriage in genealogical records (Figure 4) indicates that these individuals remained seeking marital alliances outside their hometowns. In the south, the mobility of spouses paralleled an emerging livestock economy, such as suggested by the trajectory of the Taques de Almeida family. Marital alliances in the towns associated with ranching, such as Itu, Sorocaba, and Curitiba, strengthened while a significant contingent of São Paulo-born people continued to move to these frontier towns. Furthermore, these settlements also began to send spouses to the extreme south of Portuguese America, in the territory of Rio de Grande de São Pedro, a major livestock supplier for the rest of the colony.46

If I were to choose a visualization that best encapsulates my argument, it would be this one. It shows the scale of the movement undertaken by the inhabitants of São Paulo and demonstrates, through the thickness of the lines, how kinship connected different locations. The overall impression I try to make is a space that is connected and made cohesive through family ties.

Figure 4.

Spatial trajectories of spouses in the first half of the 18th century (1700-1750), based on places of birth and marriage extracted from genealogical records. The interwoven space of the highlands of São Paulo in the 17th century acquired a broader geographic extent in the first half of the 18th century.

Inter-regional connections were stronger with the captaincy of Minas Gerais, represented by the towns of São João del Rei, São José del Rei, Vila Rica, and Mariana. Neither the month-long journey from the port of Santos, nor military conflicts between São Paulo-born settlers and “outsiders” in the first years of settlement, nor the political autonomy of the region, which became an independent captaincy in 1720, lessened the ties between the regions.47 Southern Minas Gerais and the northern part of the captaincy of São Paulo, notably Taubaté, were tightly connected. Of the 51 spouses born in this town, 19 entered wedlock in the mining region while only 14 chose to establish themselves in a different location within the limits of São Paulo. People from São Paulo, Jundiaí, and Mogi-Mirim and adjacent towns also married in the mining region, but in smaller proportions.

Portuguese-born men were the group that appeared the most among the spouses recorded in the genealogical data for the first half of the 18th century. They were listed marrying in the same regions in which the inhabitants of São Paulo were established, including older and newer urban cores of the captaincy as well as in the expanding mining zones. At least 50 grooms and a few brides found their spouses in Minas Gerais, but the majority preferred to enter wedlock in the former captaincy. The city of São Paulo, for instance, received 44 spouses from Portugal and the Atlantic islands (mostly from the Azores); other towns in the captaincy, on average, welcomed a dozen of them each. Their inclusion in the genealogical data, which register their strategy of joining local families, shows a distinct picture of wandering men looking for fortune in faraway mining regions, as often depicted in the historiography. Instead, the fact that nearly three quarters of the Portuguese spouses married in the inland towns of São Paulo suggests that they first established themselves, through marital alliances, in consolidated places where they forged local relationships that eventually enabled them to depart to the interior.

Goiás and Mato Grosso, two other important mining regions, were nearly absent from the registers of spousal mobility in the first half of the 18th century. Not only the late discovery of these regions, after the third decade of that century, account for this anomaly, but the lack of inter-regional unions between São Paulo and these new areas points to a distinct spatial dynamic. First, most of the records of those who married in Goiás and Mato Grosso did not indicate the place of birth. In fact, natives from the most established São Paulo families tended to have their places of birth under-recorded, as their attachment to their hometown was implicit in the family narrative. Birth information was more prevalent to outsiders joining these family lineages. Second, as suggested in the vignette of the first expedition that uncovered gold in Goiás, it is likely that many of the marital alliances were established in São Paulo and facilitated their movement in the interior. As in the slaving raids of the previous century, marrying locally would allow them to marshal resources face the hardships of travel. For most of the 18th century, reaching Mato Grosso would take five to seven months through a combination of riverine and overland routes, while to Goiás was a couple of months away by land.48 The movement to these regions would go unrecorded in the genealogies.

This trend changed in the second half of the 18th century. Genealogical records for this period (Figure 5) mentioned Goiás and Mato Grosso more often. Still, they indicated a different pattern in the movement: they were mostly traveling eastward, returning from the mining areas to the towns of São Paulo. The dataset shows at least 30 individuals that were in Goiás and Mato Grosso and returned to the captaincy to enter wedlock. Furthermore, they displayed a clear preference for the westernmost towns of the captaincy, with Itu and Sorocaba heading the list. The choice of returning to the captaincy of São Paulo was not unusual. These spouses were looking for partners in regions that had been associated with their families even before they were born and where they had cultivated, despite being away for many years, strong social, political, and economic connections.

Figure 5.

Spatial trajectories of spouses in the second half of the 18th century (1750-1800), based on places of birth and marriage listed in the genealogical records. Although the mobility of spouses kept the same geographic extent, the proportion of long-distance trajectories decreased during the period, favoring short-distance mobility. Connections between urban centers in São Paulo with Mato Grosso and Goiás reveal a large number of “returnees” – people that were born in the mining areas but returned to their parents’ hometowns to marry.

The sparseness of the dataset does not allow an appraisal of the scale of the flow of returnees. However, cases of two-way, multi-generational mobility, such as represented by João and Maria’s vignette at the beginning of this article, offer compelling evidence of the reiteration over time of journeys between the newer settlements in the backlands and São Paulo. Another paradigmatic case is a family headed by Isabel de Campos, who married a young man from Guaratinguetá in her hometown, Itu, in 1746. Eventually, the couple moved to Goiás and had seven children there. In 1771, when the sixth child was born in that mining district, Isabel’s oldest child was in Itu marrying a local man. In the following years, the remaining children also relocated to Itu and married there, and none of them seem to have moved again: all six of Isabel’s grandchildren listed in the Genealogia ended up marrying locally in Itu by the turn of the 18th century.

João and Maria’s or Isabel’s family mobility represents a larger pattern and illustrates the decision of moving of many colonists. These spatial practices suggest the maintenance over time of the connections between distant places and resemble, to a much larger geographic extent, the dispersed but cohesive space of the highlands of São Paulo in the 17th century. In a sense, these people developed a way of living between two or more places and became accustomed to distance and absences. Marital alliances created enduring relationships that, on the one hand, enabled mobility to new frontier zones and, on the other, guaranteed a home and community to those who returned. Indeed, the homeland was always there, and several individuals that were lured to the mining frontiers in the early years retired in the property they held or inherited in São Paulo – though these stories are less visible in the genealogical records. The fact that their return (and that of their children) seemed to happen effortlessly indicates that the ties to their hometowns never faded away.

The patterns gathered from this analysis also hint at spatial practices that are not evident in the genealogical records. While the mismatch between the place of birth and marriage provides an overall sense of circulation of people across space, the existence of the social ties after many years suggests that the volume of traffic between these locations was higher than recorded in the data. Once again, snippets of a life story, entangled in the dense web of family relationships, highlight the main characteristics of these itinerant lives.

In this section, I’m attempting to further my argument even though the main evidentiary base – the genealogical dataset – is limited. While the dataset gives the overall picture of the spatial practices of the inhabitants of São Paulo, it offers less about the texture and scale of their mobile lifestyles. These aspects of social life aren’t easily translated as data. By reconstituting the life story of Pedro Taques de Almeida Paes Leme using other sources, I tried to give the dimensions to which his life and his contemporaries' were lived simultaneously in many places.

The option of sidelining methodological discussion made this transition easier however. Since my narrative isn’t an exploration of a method and its potentialities, I could, without any embarrassment, simply move to a different approach to qualify part of the argument I was making. I didn’t feel the need to have a long discussion about the limitations of my method, for instance.

A Mobile Life in the Backlands

In 1714, Pedro Taques de Almeida Paes Leme was born in the city of São Paulo to two of the most distinguished families of the captaincy. Pedro’s mother was one of the 26 petitioners who, under the leadership of his grandfather, requested the enormous land grants in Curitiba and Minas Gerais. His family had been associated with mining since the early 17th century when his great-great-grandfather (also named Pedro Taques) accompanied the first crown-appointed explorer to inspect the mines of São Paulo and stayed in the region. Since then, the lineage of the Taques had occupied several leadership positions in the captaincy and engaged actively in slave-raiding and exploiting of the backlands. They were part of the expeditions that discovered mineral wealth in central Brazil, and several of Pedro’s close relatives were among the first Luso-Brazilian settlers of Minas Gerais. The father’s side, the Lemes family, was even more prominent. They settled in São Vicente in the mid-16th century and sprawled across several towns in the highlands of São Paulo. The family also included several sertanejos, like Pedro’s uncle Fernão Dias Paes, the leader of the famed expedition to search for emeralds. The wayfaring of the backlands was part of his family legacy.

During his lifetime, mostly spent in São Paulo, Pedro developed a strong relationship with Goiás. His father was one of the three partners of the excursion that discovered gold in that region, being responsible for raising funds and supporting the expedition while it was in the backlands. As part of the agreement with the other leaders (his brother and his brother’s father-in-law) and colonial authorities, Pedro’s father gained the right to explore the passage (that is, charge toll) of three rivers in the route to Goiás for three generations. When his father died in 1738, Pedro and his siblings inherited these rights as well as ranches in Curitiba (created in the land grants he requested with his father-in-law) and several business assets in Mato Grosso, which were managed through an agent.49

Little is known about Pedro’s younger years, besides his education in the local Jesuit school and his appointment as sergeant-major of the militia in 1737, two years after his first marriage to the daughter of the cavalry captain of Goiás. Although familiar with the region since he was young, Pedro’s first recorded trip to Goiás only happened at the age of 35, when he relocated to the mines of Pilar, a thriving mining center, in the mid-18th century. He spent five years there supervising his business and serving as a fiscal officer. After accumulating a small fortune, he briefly returned to São Paulo but soon departed for Lisbon, where he intended to petition the higher courts of the kingdom for confirmation of the rights of passage he inherited, which were under judicial litigation. The travel was untimely, as he reached the empire’s capital a few days before the catastrophic 1755 earthquake that destroyed Lisbon, including Pedro’s personal property and documents he brought to support his case. Although unsuccessful in his primary goal, Pedro returned to Brazil in 1757, holding the office of Treasurer of the Bull of the Holy Crusade (to collect indulgences sold to support warfare and rescue of Catholic captives in North Africa) of the captaincies of São Paulo, Goiás, and Mato Grosso. His experience with mining also gained him another office in the following years, Keeper (guarda-mor) of the Mines of São Paulo, in 1763, which required him to travel to several parts of the captaincy.

In the same way Pedro’s fortune was associated with the distant Goiás, it was also the source of his demise. A decade after taking office as Treasurer, one of the agents he appointed to oversee the selling of the bulls in Goiás failed to remit the proceedings, making Pedro default the royal coffers. As a consequence, he had most of his property confiscated and sold in a public auction. His reputation was also ruined. In 1771, Pedro was recorded as a resident of the city of São Paulo, living off of the products of his small rural estates, but, as his biographer noted, he kept another agent in Goiás managing gold extraction in the mining fields he still owned.50 A few years before his death in 1777, Pedro traveled again to Lisbon to appeal for his paternal rights over the route to Goiás, successfully this time. The good news came late, though, as Pedro died soon after returning to his hometown.

The vital events of Pedro’s life –birth, death, and three marriages – all happened in the same location, the city of São Paulo. Therefore, the connections to the places that shaped the course of his life were overlooked in the analysis of the trajectory of spouses. Furthermore, as with most of the people who settled in the backlands during the 18th century, it is impossible to tell how many times Pedro took the route to Goiás or any other region in which he and his family held businesses. Still, his life undoubtedly depended on events happening simultaneously in several parts of the empire. From the decision about mining policies, grants, and offices taken in Lisbon to the organization of expeditions by his ancestors, the spread and mobility of relatives, and the creation of partnerships through family and agents, the life of Pedro was carried out in this fragmented geography and only possible through his capacity to move and forge lasting connections across space.

For the crown, these spatial practices and the dispersed-but-woven geography it produced enabled the extension of its empire in the backlands at an unprecedented scale. Although not directly acting in the name of the empire, the wayfaring and settling of the families of São Paulo unlocked a massive pool of resources that precipitated the creation of the imperial bureaucracy in these new areas. These settlers composed the bodies of governance, commanded local militia, and organized the fiscal and judicial apparatuses of the state – they were the de facto representatives of the empire in these distant regions. Furthermore, their mobility also facilitated the economic integration of the backlands. Settling required the reallocation of the family assets, the formation of new commercial circuits, and the constant flow of information. Overall, the mobility of people like Pedro rendered an abstract notion of “conquest” that was claimed by the king of Portugal into a real part of the empire.

Regionalizing Networks

In the second half of the 18th century, the spatial practices of the inhabitants of São Paulo became constrained to a reduced geographic extent as inter-regional connections weakened. Over time, these family networks tended to become regional as the dynamism of the mining economy began to wear off. The genealogical records demonstrate that the percentage of spouses marrying outside their captaincy of origin, including both São Paulo and Minas Gerais, decreased significantly during this period. The only town that continued sending spouses to distant places at the same rate was São José del Rei, a mining town in southern Minas Gerais, whose natives married in twelve different locations of three captaincies (mostly in São Paulo.) Most likely, they represent a large group of returnees from a region that had strong connections with traditional family branches of São Paulo. Nevertheless, the proportion of spouses marrying outside their captaincy of origin nearly halved in the other towns.

| Place of Birth | 1700-1750 | 1750-1800 |

|---|---|---|

| Captaincy of São Paulo | ||

| Itu | 4.4% (45) | 3.4% (87) ↓ |

| Jundiaí | 18.2% (11) | 7.5% (93) ↓ |

| Mogi das Cruzes | 25.0% (20) | 12.7% (63) ↓ |

| São Paulo | 10.9% (128) | 4.4% (248) ↓ |

| Taubaté | 31.4% (51) | 18.9% (95) ↓ |

| Captaincy of Minas Gerais | ||

| São José del Rei | 14.3% (14) | 14.6% (41) ↑ |

| São João del Rei | 29.4% (17) | 18.6% (355) ↓ |

Table 1. Percentage of spouses that married outside their captaincy of origin. Data suggests, in most cases, a decrease in long-distance relationships. Numbers in parentheses indicate the total number of observations (i.e., the total number of marriages for the period). The table only includes towns with more than ten observations.

One of the main virtues of maps is to offer a quick way of considering distance, in its multiple forms, as part of the analysis (as summarized in Tobler’s “first law of geography”: “near are more related than distant things."*) In this article, Figures 3 to 5 attempt to convey the idea that, even though locations are set apart in space, strong family ties connected them and structured inter-regional exchanges in an expanding territory. The location and geographic scale in which certain events happened (i.e., birth and marriages) were crucial to the argument, and maps were effective ways of visualizing the phenomenon. However, in many cases, maps are not necessarily the only or the most effective form of representing or analyzing spatial phenomena. In this case, as distance is not a primary explanatory variable and the data selection is small, tables are quite effective because they capture broad trends (highlighted with the “trend arrows”) while offering granular information. This table and the next one show general patterns that are geographically discrete (that is, not influenced by the other locations) and happened in spite of their location. *See Waldo Tobler, “A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region,” Economic Geography, 46 (1970): 236.

At the same time, certain regional connections became stronger. For example, Itu and Sorocaba, which were about a day of travel from each other, increased the number of spouses they exchanged. Families from Itu increased the proportion of bachelors they sent to Sorocaba to enter wedlock, from a fifth to a quarter of the total number of recorded marriages. The same happened in the opposite direction: 42% (of 115) of the documented marriages of Sorocaba-born people happened in Itu, in contrast to the previous 35% (of 37.) Through these connections, this livestock-producing region became increasingly socially cohesive.

This process of regionalization is also visible in the increasing proportion of people that died in the same places they entered wedlock. With the notable exception of the city of São Paulo, the tendency of permanently settling after marriage became stronger as the 18th century passed (Table 2.) Marriage and the formation of a new household reduced or ceased the mobility of individuals. Furthermore, the outwardness of São Paulo – the only place that decreased in post-marriage permanent settling – is deceptive. Besides four individuals that died in Goiás and Mato Grosso after marrying in that city, the remaining 119 recorded colonists died either in São Paulo or one of the inland towns of the captaincy. The shift of the direction of the movement, from the mining regions to nearby towns, marked the increasing centrality that the city had in the spatial organization of the captaincy. São Paulo had already been the central node of the urban network in the captaincy since the early 17th century, but colonists gravitated towards frontier towns as they concentrated the most coveted resources. By the end of the century, the situation changed. The political restoration of the captaincy in 1765 strengthened São Paulo’s hegemony, and the exchanges within the captaincy became more dependent on connections to the capital.

| Towns | 1700-1750 | 1750-1800 |

|---|---|---|

| Itu | 73.4% (128) | 87.8% (123) ↑ |

| Jundiaí | 75.9% (29) | 98.9% (95) ↑ |

| Mogi das Cruzes | 81.1% (53) | 87.8% (47) ↑ |

| São Paulo | 71.3% (147) | 45.5% (124) ↓ |

| Taubaté | 79.3% (29) | 87.9% (33) ↑ |

Table 2. Percentage of recorded deaths in which the deceased died in the same place as he or she was born. The growing proportion of this type of case suggests the decline in geographic mobility towards the end of the 18th century.

The restoration of the captaincy also changed the imperial attitude towards the mobility of the inhabitants of São Paulo. In 1750, the new secretary of state, Marquis de Pombal, rose to power, leading a series of administrative reforms in Portugal and its overseas empire.51 After arriving in 1765, new governor D. Luís Antonio de Sousa implemented economic and military reforms and reorganized the captaincy’s territory. He founded towns, carried out censuses, enacted anti-vagrancy laws, and implemented state-sponsored migration to the frontier regions and other policies that conflicted with a quite mobile population. The governor envisioned a captaincy formed by a collection of well-ordered, disciplined settlements under his firm control – and he perceived the wayfaring and dispersion of the people of São Paulo as a considerable obstacle to it.52

Still, despite the challenges posed by colonial authorities, the mobility of the inhabitants of São Paulo was repurposed in the imperial narratives and became instrumental for geopolitical goals. In 1750, when Spanish and Portuguese ambassadors came to the negotiation table to discuss the inter-imperial boundaries in the Americas, the footprints left by their spatial practices were vital to sustain Portuguese ambitions of an enlarged territory. By suggestion of Alexandre de Gusmão, a São Paulo-born diplomat who led the negotiations for the Portuguese camp, the plenipotentiaries meeting in Madrid adopted the legal principle of uti possidetis, which granted possession to those who occupied the land in practice, to solve the territorial quarrel.53 The settlements the people of São Paulo created and sustained in the interior, even though small and sparse, and the extensive geographic knowledge they produced allowed the Portuguese to consolidate the frontier westward. Indeed, the map used during the negotiations – the well-known Mapa das Cortes – included information provided by these early explorers.54