Protestant Letter Networks in the Reign of Mary I:

A Quantitative Approach

Citation for Original Article:

This article uses mathematical and computational techniques developed by network scientists to reconstruct and analyze the social and textual organization of the underground community of Protestants living in England during the reign of Mary I, using an important body of original letters now held in the British Library and Emmanuel College Library, Cambridge, as well as early printed correspondence. At the outset the aim of this project was more methodological than historical. In many ways it was a proof-of-concept study that paved the way for further collaboration between us: it sought to determine whether the methods of network analysis, which were gaining such traction in numerous fields, were also pertinent to the study of historical communication and communities.

If we were to publish this article now, we would make our roles in its development more transparent. In some fields author order might signify certain roles: in many fields the first author will have taken a lead on the paper, and the final place in the author list is often reserved for the supervisor or most senior member of the team. It is now best practice in the sciences, and becoming more common in the digital humanities, that authors document their different contributions. Many journals are now encouraging use of the Contributor Roles Taxonomy). For a nice example of where some of Ruth’s collaborators recently employed this as film-style credits, see this article, and the accompanying blog post. In our case, the ordering of our names is merely alphabetical. Our roles in the development of the article were very different, building on our disciplinary expertise. Ruth, at this point in her career, would have described herself as a literary historian with specialisms in Tudor literature, court culture, and Church History. Sebastian would have described himself as a physicist with expertise in network science and the study of structural and functional complexity in biology. Accordingly, Ruth conceptualised the project, undertook the archival work needed to construct the underlying data set, collaborated on the interpretation of results and design of further rounds of network analysis, and led the writing and editing. Sebastian prepared the data set from Ruth’s records, led the implementation of the network analysis, collaborated on the interpretation, and contributed to the writing and editing.1

In 1533 Thomas More took possession of a manuscript containing an evangelical tract on the topic of transubstantiation written by John Frith. Despite being unpublished at this time, More felt this text required refutation and penned A Letter […] impugnynge theerronyouse wrytyng of John Fryth. More’s concern was the potential dissemination of the work. By the time his answer to Frith’s tract was published he had been able to acquire three manuscript copies, which confirmed to him that the text was being copied, and led him to fear an organised network of evangelicals working together to produce and disseminate texts. He imagined this model of dissemination as a canker spreading through a body:

For as saynte Poule sayth, the contagyon of heresye crepeth on lyke a canker. For as the canker corrupteth the body ferther and ferther, and turneth the hole partes into the same dedely sykenesse: so do these heretykes crepe forth among good symple soulys / and vnder a vayn hope of some hygh secrete lernynge, whych other men abrode eyther wyllyngly dyd kepe from them, or ellys coulde not teche theym / they dayly wyth suche abomynable bokes corrupte and destroye in corners very many before those wrytynges comme vnto light[.] 2

St Paul’s canker metaphor (2 Timothy 2:17) is used here by More as a rhetorical device to alarm his readers about the way that he perceived heresy spreading throughout England, largely undetected. But this metaphor also shows striking insight about the ways that underground religious movements work, prefiguring discoveries about the structure of social networks by some five centuries. Recent research in the field of quantitative network analysis has shown that viruses and epidemics share key patterns of dissemination and growth with religious ideas, innovations, viral internet phenomena or new products.

In a series of key publications in the 1990s and early 2000s, scholars such as Albert-László Barabási, Reka Albert, Duncan J. Watts and Steven Strogatz showed that a huge variety of real-world networks – such as, for example, neural networks, transport networks, biological regulatory networks and social networks – share an underlying order and follow simple laws, and therefore can be analyzed using the same mathematical tools and models.3 These publications build on work from various different disciplines, such as sociology, mathematics and physics, which stretches back some decades. The theoretical approaches of social network analysis have already made an impact in the fields of historical corpus linguistics, coterie studies, and the history of science, amongst others; but the application of mathematical and computational techniques developed by scientists working in the field of complex networks to the arts and humanities is a relatively recent development, and one that is gaining increasing traction, offering as it does both technical tools and a sense of contemporaneity in a world now dominated by social networking platforms. Despite these developments, however, there is still much work to be done before these statistical methods are embedded within the literary historian’s toolbox. All too often the word “network” is used by scholars in this field as a useful metaphor – in much the way that Thomas More wielded the word “canker”. This article will demonstrate how the mathematical tools employed by network scientists offer valuable ways of understanding the development of underground religious communities in the sixteenth century, as well as providing different approaches for historians and literary scholars working in archives.

While it is not possible to prove More’s fears about the extent and organisation of evangelical communities in England during the 1530s due to lack of documentation, considerable evidence for the structure of the underground Protestant communities functioning in the Catholic reign of Mary I survives in collections of correspondence. Early modern correspondence provides a unique textual witness to social relations and structures. Gary Schneider has described Renaissance letters as “sociotexts”: as “crucial material bearers of social connection, instruments by which social ties were initiated, negotiated, and consolidated."4 Letters were the method by which people sought patronage, garnered favor and engineered their social mobility; they were a means of communicating alliance, fidelity, and homage; and they could be used “as testimonies, as material evidence of social connectedness”.5 The modern perception of private correspondence was one that simply did not exist in the early modern period. Instead, epistolary conventions implicated multiple parties in the composition, transmission, and reception of letters. Common letters (intended for more than one recipient or written by more than one sender) most clearly demarcate the idea of an epistolary community, but senders also extended the reach of their correspondence by directing the recipient to pass the letter on to other people, by enclosing commendations, additional messages, tokens, and even letters for other recipients, and by entrusting additional oral messages to the letters' carriers. Carriers or bearers were vital members of epistolary communities, described by Alan Stewart and Heather Wolfe as the “lifeline” between families and friends, court and country.6

Letters, then, can tell modern scholars about the working of specific social groups: who its members were, and how they related to one another. Thanks to the efforts of the famous martyrologist John Foxe and his associates, 289 unique letters survive in print and manuscript that were written either by or to Protestants residing in England during Mary’s reign. These letters provide crucial evidence for the social organisation of the Protestant community in England at that time. The letters from Protestant leaders – former bishops and archbishops such as Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Ridley, and John Hooper – show that they continued to shape the Protestant movement from their prison cells, providing pastoral guidance and doctrinal instruction for co-religionists inside and outside the prison, as well as coaching other prisoners for martyrdom. The correspondence also outlines the infrastructure that enabled these leaders to write and be disseminated, including a system of financial sustainers outside the prisons, of copyists and amanuenses in and between prisons, and a supply of carriers who enabled the prisoners letters and enclosed writings to reach recipients across England and the continent.

Ruth had previously consulted these letters in the research for her doctoral thesis, which formed the basis of her first book The Rise of Prison Literature in the Sixteenth Century (Cambridge University Press, 2013). See especially chapter 3. Her deep prior knowledge of this collection meant that it provided a good test case for our first experiment in the application of network analysis to early modern correspondence.

Quantitative network analysis allows us both to visually map the social network implicated in this body of surviving correspondence, and to measure the relative centrality of each of its members using a range of different mathematical tools. These methods allow the kind of large-scale picture that has been described by Franco Moretti as “distant reading” and by Matthew Jockers as “macroanalysis”.7 These terms describe a whole variety of different statistical and digital methods, but what they all have in common is that they “allows for both zooming in and zooming out” (what Martin Mueller has termed “scalable reading”).8 Network analysis is one such tool: it allows us both to see the entire Protestant community implicated in this body of correspondence, and to identify the individual people and letters that require localized attention and close reading. Our analysis reveals not only expected patterns – that martyrs are central to the organisation of this community – but also some surprising facts: that letter carriers and financial sustainers (especially female sustainers) are more important than we may have previously suspected; and that their significance increased as the martyrs died. The techniques of network analysis, therefore, help us to counterbalance the spectacular bias of John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, popularly known as the “Book of Martyrs”, which is the main contemporary source for documents on the persecution of the Protestant church, but which almost exclusively celebrates those who lost their lives at the hands of the Catholic state. As Thomas Freeman has remarked, “to ignore the majority of Marian Protestants who did not die for the gospel is to study the steeple and believe that you have examined the entire church”. 9

I. RECONSTRUCTING AN EPISTOLARY COMMUNITY

Reconstructing the church beneath the steeple requires a combination of archival work and computational analysis. The 289 letters that form the basis of this study are scattered throughout Foxe’s papers and publications, and two further print sources: Many of the letters were printed in Foxe’s “Book of Martyrs”, first published in 1563, and the associated publication Certain Most Godly, Fruitful, and Comfortable Letters of … True Saintes and Holy Martyrs of God, edited by Henry Bull but issued under Miles Coverdale’s name and printed in 1564; three letters by John Careless printed at the end of Nicholas Ridley’s A pituous lamentation of the miserable estate of the churche of Christ in Englande in 1566; twelve letters are made available in a Victorian anthology;10 and several further letters survive which exist in manuscript only.11 Many of the printed letters also survive in manuscript and holograph versions in Foxe’s papers, held in the British Library and Emmanuel College Library, Cambridge. These copies have been crucial to this study as many of them contain material edited out of the printed versions, including information about the Protestant community, such as the items of personal news with which some letters concluded, greetings to family and friends, as well as references to carriers.12

In the spirit of transparency, it is useful to share how the notes that Ruth took were turned into the correct data structure for analysis by Sebastian. It was not yet apparent if it was worth Ruth acquiring a new set of skills as this was an experiment to see if network analysis was even useful for the study of historical letter archives (although we were hopeful). She therefore gathered the data into a Word document, where an entry for a letter may look like this:

Fol 28. Heinrich Bullinger (Zurich) to John Hooper (Fleet?) 10 October 1554 (LM, 163-6 in Latin, 166- ; 1570….) (Mentions having received 2 letters from Hooper in Sept of previous year and May of this year.) B asks that he be commended to H’s fellow prisoners, Thomas Cranmer, Nicholas Ridley and Hugh Latimer (and all the rest of the prisoners). Says he will write also to Hooper’s wife because he heard she was in Frankfurt.

This information could then be used by Sebastian to create an edge list for the relationships in those letters. In this case, the result is 9 edges, which can be structured as an edge list as follows. Columns are: Sender, Recipient, Relationship type (we had a taxonomy of 11 relationship types, discussed further below, each denoted by a number 1-11), Date (from, following the format YYMMDD), Date (to). The two dates provide a way to specify a date range where there may have been some uncertainty about the date; if an exact date is given in the letter, the two dates would be the same.

| Heinrich Bullinger | John Hooper | 1 | 541010 | 541010 |

| Heinrich Bullinger | Thomas Cranmer | 3 | 541010 | 541010 |

| Heinrich Bullinger | Nicholas Ridley | 3 | 541010 | 541010 |

| Heinrich Bullinger | Hugh Latimer | 3 | 541010 | 541010 |

| Heinrich Bullinger | John Hooper’s wife | 4 | 541010 | 541010 |

| John Hooper | John Hooper’s wife | 8 | 541010 | 541010 |

| John Hooper | Thomas Cranmer | 6 | 541010 | 541010 |

| John Hooper | Nicholas Ridley | 6 | 541010 | 541010 |

| John Hooper | Hugh Latimer | 6 | 541010 | 541010 |

This paragraph discusses the taxonomy of 11 edge types that we created to encode different kinds of relationships described within letters. Although we created this taxonomy at the data collection stage, you will see that in the analysis below we collapse them into 2 edge types: letter edges and non-letter edges. However, this more granular taxonomy could be used to answer other questions that we do not touch on.

These documents, and letters in general, offer themselves to network visualization and analysis in a much more straightforward way than other forms of literature. A network is a set of relationships between objects or entities. We normally refer to the objects or entities as nodes in the network and their relationships as edges or ties. For example in an ecological network different species would be nodes and the edges might represent which animal eats which other animal; in the worldwide web, the web pages would be nodes and the hyperlinks edges; and in a social network, such as this Protestant epistolary community, people are the nodes, and the relationships linking them are the edges. The material we have utilized includes all the letters where either the sender or recipient was residing in England,13 family correspondence (regardless of doctrinal position), and letters between Protestant factions. In order to focus on the community’s internal workings, we have excluded letters sent by Protestants to the authorities or to opponents. We have also had to exclude correspondence in which the sender or recipient is anonymous, with the exception of those letters where other social links are found. In the first instance we read through each of the 289 letters that fulfilled these criteria, recording the following data: who the letters are from and to, the location of both of these parties, the date of composition (where given or ascertainable), and any commendations or reported contacts. We then categorised the links that arose between the members of this community as follows: letter links (between sender and recipient); requested links (through a commendation, between sender and commendee); implied links (through a commendation, between recipient and commendee); reported links (where a conversation or other exchange was relayed); messenger links (where a messenger is named, making them an intermediary node between sender and recipient); spousal links; and sibling links. Once we had gathered this data into a plain text flat file, we used Python code – more specifically the algorithms contained in the Python NetworkX library – to analyze the network.

We spent a lot of time thinking about how much technical detail we should put in an article aimed at a readership in literary history. We didn’t want to alienate our reader; but at the same time, we wanted people to be able to follow our steps. We therefore decided to provide short and accessible prose descriptions of the technical processes that would make sense to colleagues from the digital humanities, but not get into the details of the code, which we thought might act as a barrier to our less technical readers. The downside is that if anyone wanted to reproduce our results they would need to approach us for the data and code. However, in retrospect, we realise there is a better way of squaring the circle. In our current collaborations, for example, we are seeking to make all of our data (where permitted) and code available alongside the research outcomes so that the results can be recreated, or the data/code adopted and used for other purposes. Such an approach allows us to keep the main text fairly clean and accessible, and the technical details annexed for those that are interested and able to make use of those materials. We have benefited immensely by collaborating with other scholars who are thinking carefully about reproducibility.

What emerges from this data is a surprisingly large community, with 377 members and 795 edges, or social interactions. Many studies in quantitative sociology analyze much smaller social networks, with fewer than 100 nodes. For example, one of the classic data sets used to test network analysis algorithms is the social network of a Karate Club with 34 nodes and 78 edges. 14 The reason is that, until the advent of online social networks, sociologists were restricted to labor-intensive surveys as a means of compiling social network data. So our dataset is large enough to provide meaningful statistical results. Unlike the Karate Club network, however, which is complete and self-contained, our reconstructed Protestant network is only partial. Historic letter collections are subject not only to the vicissitudes of time, but also the bias of collectors. Foxe and Bull primarily printed letters by martyrs; and the collectors that provided these editors with correspondence were also more likely to preserve the missives of those who died for their faith. We cannot know how many more letters there were that are now lost. For example, the martyr Richard Woodman wrote letters that have not survived; conversely, we would probably not have many of the letters of John Careless if Thomas Upcher had not gathered up letters written by the martyrs to Protestants who ultimately joined the Aarau congregation. However, it is important to remember that this is not an uncommon problem: the vast majority of network analysis deals with incomplete networks in the real world, and any statistical treatment of biases has to make assumptions about the distribution of missing links or nodes. In the following analysis we are alert to the bias of the collection and its likely effects on our findings. This bias will necessarily exaggerate the seeming prominence of martyrs in the topology of the network. The detection of infrastructural figures such as couriers and sustainers, however, is much less affected by this bias, as these individuals are identified using centrality measures such as betweenness and eigenvector centrality (which will be explained further below).

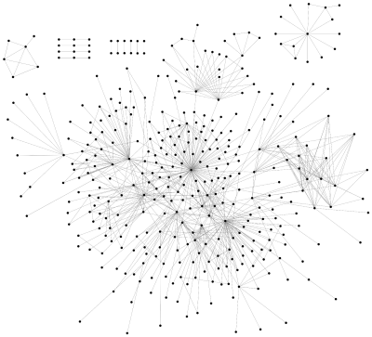

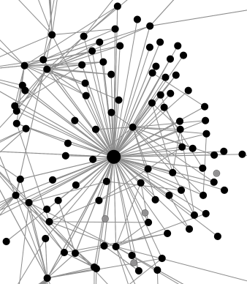

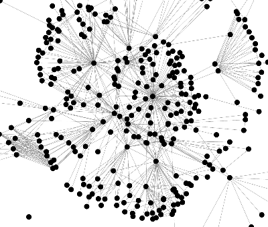

This figure is generated using a force-directed layout, probably the most common way of visualising a network. The advantage is that, generally speaking, nodes that are closer together in terms of their network connections also appear closer in space. Particularly for dense networks however this equivalence quickly breaks down, resulting in opaque ‘hairballs’ that yield little insight in the structure of the network. Another caveat that applied to this and many other layout algorithms is that they produce different results every time they are run, as there are infinitely many ways to draw the same network.

Fig. 1:

The entire network of social interactions.

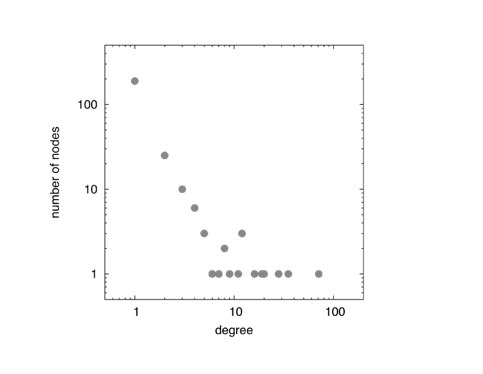

By compiling this data we were able to generate a visualization of the Protestant community as a network using OmniGraffle (figure 1; we used the same program to generate all our figures). Such an image is very powerful: this community, which existed 450 years ago and which was only partially recorded by Foxe, is literally mapped out before our eyes. From this visualisation we can immediately see who is important. The word “important” is used here, not to make a value judgment, but merely to denote figures who are structurally central to the network’s topology, which is something that can be measured with some accuracy. As in many network visualizations, the Protestant letter network in figure one is force-directed, meaning that the algorithm creating the network layout models the network edges as physical springs so that any deviation from a given equilibrium length is counteracted by a force that is proportional to the displacement.15 As a result the most connected nodes (for example, those with the greatest number of edges or links) appear closer to the centre, and those who have the least connections appear at the network’s periphery. Therefore, right at the centre, with many edges radiating from them, are figures such as John Bradford, John Careless, Nicholas Ridley and John Philpot. This is much as we would expect. They are special figures: they are martyrs who wrote a lot of letters and featured prominently in Foxe’s famous martyrology. But they are also special in another way. They are what network analysts would call hubs: nodes with an anomalously large number of edges. By comparison, many of the other nodes in the network have few, or even only one or two edges. Hubs are an extremely important component of any network. In social networks, as Barabási has observed, they are the kind of people who create trends and fashions, make important deals, and spread fads.16 If we plot the number of edges that each node in this network has on a graph (figure two) we can see that they follow a classic power-law distribution, which is typical of many real-world networks; there are very few nodes with many edges, and many nodes with few. This clearly demonstrates the atypical nature of the hub within a network. And it tells us that figures like Bradford, Careless and Ridley had a significant impact on the structure of the network; without them it would look very different.

Fig 2:

The degree distribution of the network of social interactions.

In this paragraph we discuss the graph depicted in figure 2. Plots like this are not perhaps the kind of visual representations that people might expect to see in an article that foregrounds network analysis. However, whereas force-directed network graphs can be difficult to ‘read’ meaningfully, these plots are a powerful way to reveal significant quantitative trends. We’ve also used such plots to good effect in another article, where we compare individuals in terms of two particular network metrics and show that the outliers with regard to these metrics turn out to be double agents and conspirators, due to their particular connectivity. See Ahnert and Ahnert, ‘Metadata, Surveillance, and the Tudor State’, History Workshop Journal 87 (2019), 27-51

Readers familiar with network analysis will see that we initially applied a series of very standard metrics in order to analyse our network (degree, betweenness centrality eigenvector centrality, etc.), to understand its structure and organisation, and to test whether the things they revealed were supported by Ruth’s prior knowledge of the letter collection. One important thing that we stress below (and elsewhere) is that not everything that quantitative or computational methods reveal will be new. The call for digital humanities research to be transformative and to upend our previous findings - although arising in part from certain key publications within the digital humanities (for example Franco Moretti’s ‘Slaughterhouse of literature’, Modern Language Quarterly (2000) 61 (1): 207–228) - has resulted in unrealistic expectations about what a meaningful contribution constitutes. In fact, developing a computational method or model that is able to predict results that correspond to already known facts and phenomena is good because it means that it is doing what we need it to. Why then develop the method if it tells us what we already knew? Well, it might tell us 19 things we already knew, and one thing that we did not; it is that one thing that allows us to make an incremental contribution to scholarship. Furthermore, very often some of the 19 things we already ‘knew’ were, in fact, things we had some evidence for, or a very good hunch about, and can now verify quantifiably.

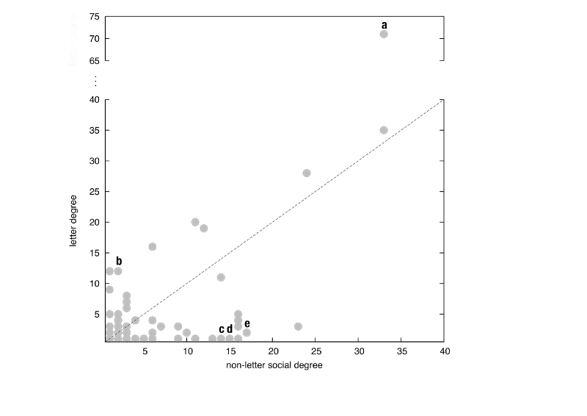

Fig 3:

Letter degree versus non-letter social degree. John Bradford (a), Henry Hart (b), Barthram Calthorpe (c), John Bradford’s mother (d) and Heinrich Bullinger (e) are highlighted.

This is all quite unsurprising for historians familiar with Marian history. But actually, it is extremely important that the method confirms what we already know. That means it works, and it means that we can put some trust in it when it draws attention to things we might not have observed before. The graph in figure 2, however does not distinguish between letter links and what we might call social links, that is, all those links created through other kinds of social interactions and relationships described within the letters. If we distinguish these, a more nuanced picture of the different roles that characters played in the epistolary community begins to emerge, as we can see in figure 3. Here we have plotted “letter degree” against “non-letter social degree”, in other words the number of letter connections for a given individual versus the number of his or her social connections other than those mediated by letters. A plot of these properties for the 377 nodes in this social network reveals a cluster around the bottom (which shows low letter degree, meaning that few of their edges represent letter exchanges), with only a few along the diagonal line (where letters sent and received corresponds to the node’s social interactions forged via other means). On the whole we see that those situated above the diagonal line tend to be martyrs or other significant religious leaders. The reason for this is that many of them were imprisoned, and so they undertook their ministry largely through letters because it was difficult to make and maintain relationships through other means. John Bradford, as an outlier at the very top right of the graph (a), provides an exaggerated version of this tendency. He wrote the most letters of all the martyrs, 119 in total, and received 19. What his position clearly shows is that his interactions with other people in the network were heavily reliant on letter interactions, but that he also had a broader circle of interactions that were independent from or additional to the links made through his correspondence. We learn about these from reported conversations, or from the inclusion of commendations (greetings or messages to be passed on verbally by the letter’s recipient). The reason for this high number of social links can be put down in part to his role as one of the chaplains in ordinary to Edward VI, during which Bradford had travelled through the country preaching reformation, in Lancashire, Cheshire and possibly beyond. This was a man who already had a lot of social connections; and he sought to maintain and further them during his incarceration

A contrasting example is Henry Hart (b), who is positioned right over near the Y-axis, a good distance above the diagonal line. This shows us that almost all his interactions within this network were via letter; barely any come through other means. Hart was a leader within a small factious Protestant group known as the Freewillers. The Freewillers were the first English Protestants to establish organised congregations that challenged the authority of the Protestant clerical leadership on the doctrine of predestination. Active from around 1550 to c. 1560, this group argued for a separation from the new Reformed Church, and can therefore be seen as the first advocates of Separatism in English history. The emphasis among some members of this community upon on separatism explains Hart’s almost total lack of social links to the main body of the orthodox Protestant network through means other than letters. Why seek commendations from your opponents? Rather, Freewillers sought to achieve conversion through the circulation of treatises and by visiting those they deemed susceptible. Hart’s position is a sign of the group’s social isolation: he was regarded as an adversary rather than an ally, as will be discussed further below.

In direct contrast to Hart’s position are the numerous nodes situated along the X-axis. Their position indicates that they take part in the social network only through means other than sending or receiving a letter: through commendations, implied links, reported conversations and relationships, or filial links, for instance. They are not in direct correspondence with the main movers in the Protestant network, such as the martyr-figures we see plotted above the diagonal line. Another group, sitting just above them, have had correspondence with one, two, three or perhaps even four different people, but they are implicated in the network mostly through other kinds of social interaction. Examples are Barthram Calthorpe (c), John Bradford’s mother (d) and Heinrich Bullinger (e), situated far to the right of the graph, but very close to the X-axis. In each case we know them to be – or the letters paint them as – points of contact with the wider Protestant community in a particular location. Heinrich Bullinger, of course, was an important Protestant leader in the exile community at Zurich; John Hooper sought to sustain contact with this vital hub within the continental Protestant community for personal reasons, asking him to write to his wife Anne who had taken their children into exile in Frankfurt.17 In a different way, John Bradford used letters to his mother as a gateway to a broader community of co-religionists in the area around Manchester, where he grew up, including, amongst many others, figures such as John Traves, Thomas Sorrocold and his wife, Roger Shalcross and his wife, Laurence and James Bradshaw.18

When writing this article, we thought very hard about the balance we should strike between quantitative approaches and the use of close reading to validate our assertions. We were trying this out for the first time. Developing our practice since then we have nuanced our thinking about the uses of the macro-, micro- and meso-scales of analysis, and how a different balance between those registers might work in different publication venues. For a more thorough reflection on this, see Ahnert, Ahnert, Coleman and Weingart, The Network Turn: Changing Perspectives in the Humanities (Cambridge University Press, 2020), chapter 6, available open access here: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108866804

Perhaps the clearest illustration of how martyrs used letters to create and maintain links within the Protestant community beyond their prison cell is one of the two letters that Bartlett Green sent to Barthram Calthorpe of the Middle Temple. This letter, which was sent not only to Calthorpe but also to Mr Goring, Mr Farneham, Mr Fletewode, Mr Rosewel, Mr Bell, Mr Hussey, Mr Boyer (probably William Bowyer)19 and “other my Maisters of the Temple”, on 27 Jan 1556, contains the following instructions and commendations:

Master Fletewodd I beseche yow remember wyttraunce and Cooke, too singular men amongst Common prisoners. Master Farneham, and Master Bell, with Master Hussey (as I hope) will dispatche Palmer, and Richardson withe his companions. I praye yow Master Calthorpe think on Iohn Groue an honest poore man, Traiford and Rice Apprice his accomplices. My Cosyn Thomas Witton (a scriuener in Lomberdstrete) haue promised to further their deliuerie, at the leaste he can instructe yow whiche waye to worke. I doubt not but that Master Boyer wil labor for the good wife Cooper (for she is wourthie to be holpen) and Ber[n]ard the french man. There be also dyuers other well disposed men, whose deliueraunce yf ye will not labor for: yett I humblely beseche yow to seeke theire relefe as yow shal see cause, namely of Harry A price, Launse Lot, Hobbes, Lother, Homes, Carre, and Beckingham, a younge man of goodlie gyftes in witt, and learninge and (sauinge that he is somewhate wylde) likely to do well hereafter. There be also ij women Conyngham and Alice Alexander that may proue honest. For these and all other poore prisoners here I make this my humble sute and prayer to yow all my masters, and especiall good frendes.20

Green makes a long list of requests of each of the letters' recipients, both individually and as a body, to do his work outside the prison. He asks them to seek the “deliueraunce” of various co-religionists from prison, and failing that, to ensure their financial support. Therefore, we can see that even though Calthorpe sends no letters, through Green’s use of his contacts outside prison he is implicated in a significant web of requested and implied links, making him an important connecting figure within the social network.

What is interesting about this simple graph, then, is that it points us to a person who sent no letters within the surviving body of correspondence, and whose name is only mentioned in passing within Foxe’s “Book of Martyrs” (in the printed version of the letter above).21 It gives us pause to think about the significance of figures like Calthorpe, who are virtually unknown to historians. What did they offer? To what extent was the survival of Protestantism in Marian England ensured by them? Calthorpe is just one of a large of people who are highly connected despite sending or receiving relatively few letters. Using measures that detect the relative connectedness of each member of this dispersed Protestant community, we find that some surprising figures are highlighted as being significant; further analysis shows that they each have a vital infrastructural role within the network.

II. NETWORK INFRASTRUCTURE

One of the challenges in writing this piece was how to gloss technical words for a readership in literary history. In the talks we gave on this research before writing up the article, we experimented with different formats, in some cases putting all the technical explanation up front, like a methods section (which is very common in science papers). However, we found that we lost people with this approach because the concentrated technical explanations represented too much of a hurdle to jump over before the audience got to more familiar terrain. We therefore decided that it was best to give people the technical background as and when it was needed, and really emphasise its utility to literary-historical research questions. You will therefore find explanations like the following ones scattered throughout the article.

A network is a collection of links, which can be combined into a myriad of possible paths. The measurement of these paths is a crucial way of establishing the ranked importance of the people in that network. “Betweenness” is one such measurement: for any two nodes in a network, there is a shortest path between them, and betweenness tells us how many of these shortest paths go through a given node. In other words, it shows us how central a particular node is to the network’s organisation, and how important it is in connecting other people. We took two measurements of betweenness, one of the letter network (just senders and recipients) and one of the entire social network, and ranked all the nodes accordingly. The top twenty nodes measured in terms of social betweenness (ie. the whole network) were:

1) John Bradford, 2) John Careless, 3) John Hooper, 4) John Philpot, 5) Laurence Saunders, 6) Nicholas Ridley, 7) Robert Smith, 8) William Tyms, 9) Bartlett Green, 10) Anne Smith, 11) George Marsh, 12) Barthram Calthorpe, 13) Bowyer, 14) Augustine Bernher, 15) Henry Hart, 16) Rowland Taylor, 17) Margery Cooke, 18) Thomas Hawkes, 19) Robert Glover, and 20) Thomas Whittle.

For letter betweenness the findings were similar:

1) Bradford, 2) Careless, 3) Hooper, 4) Philpot, 5) Ridley, 6) Green, 7) Hart, 8) James Bradshaw, 9) Marsh, 10) Tyms, 11) Saunders, 12) Taylor, 13) John Jackson, 14) Whittle, 15) Nicholas Sheterden, 16) Richard Gibson, 17) John Tudson, 18) Bernher, 19) Thomas Cranmer, and 20) Stephen Gratwick.

Some of these figures are unsurprising: the figures ranked at 1-9, 11, 16, and 18-20 in terms of their social betweenness, and 1-6, 9-12, 14-17, 19-20, in their letter betweennes, are all martyrs who wrote a number of letters, and feature prominently in Foxe’s martyrology. Several of them, such as Bradford, Careless, Hooper, Philpot, and Ridley are classic examples of hubs. The many letters and commendations they sent and received generate a large number of edges, which in turn helps to create short paths between any two nodes in the system. Accordingly, they make the world of this particular epistolary community very small despite a geographical spread from Zurich to Manchester. Sheterden is included in this martyr category, as he was executed for his faith and his death was recorded by Foxe; yet he is believed to have retained his belief in free will until the end. A number of other Freewillers also feature in the list, including the leaders Hart and Jackson, and those who defected from this separatist group, including Gibson and Gratwick. The significance of this community will be discussed further below.

Hubs in networks benefit from a rich-get-richer effect in historiography: they are the foci of further studies because their significance has already been stated, and there is more data about them. Network analysis provides a set of tools that helps us to move beyond this kind of hub-focused significance, showing us ways that we can recover the importance of seemingly minor figures in the archives. Importantly, though, this is not inherent in the measures available to us, but rather a choice in how to use them. One of our aims in using network analysis for the study of this letter collection, and one that has remained key in our subsequent work, was the desire to re-centre marginalised historical figures.

But other figures within these top-twenty rankings are altogether more anonymous: they are neither martyrs nor separatists, and their names are mentioned only in passing in Foxe’s “Book of Martyrs”, if at all. These are Cooke, Calthorpe, Bowyer, Anne Smith, Bradshaw and Bernher. Calthorpe, Bowyer, and Anne Smith share similar roles in their relationship to the celebrated martyrs of the Marian reign, funnelling goods, commendations and instructions from prisoners to communities elsewhere in England. Like Calthorpe, Bowyer was one of the recipients of the letter above sent by Green to members of the Middle Temple (“I doubt not but that Master Boyer wil labor for the good wife Cooper “). Anne Smith was the wife of the martyr Robert Smith, and received a number of letters that were accompanied by financial aid provided by her husband’s fellow prisoners, Thomas Hawkes, Simpson (probably John) and his wife, Watts, John Ardeley, John Bradford, Thomas Iveson, John Launder, “father Herault”, William Andrew and Dirick Carver.22 Cooke, it seems, channelled goods and money in the opposite direction, into the prisons; but her significance is more clearly understood when she is considered alongside a group of similar women discussed below.

The other two figures who might be grouped together are Bernher and Bradshaw. Statistically Bradshaw looks insignificant: Bradshaw wrote only one letter (to George Marsh) and received only one (from John Bradford). Bernher is a little more impressive: he wrote two letters and received 12, from 4 separate people, giving him the second highest letter-in strength (i.e. the ranking of the number of letters received) of all the 377 nodes. But there is something more significant about these men that accounts for their betweenness: both were used as couriers by the martyrs and their co-religionists. Bernher is a particularly significant figure. This Swiss reformer, who had settled in England and became Hugh Latimer’s secretary and confidante, is mentioned in numerous letters as a trusted courier, especially of letters to and from the London jails. He aided imprisoned leaders such as Bradford, Latimer, Ridley, and Careless, smuggling writing materials in, and letters and other writings out. He recorded accounts of Latimer’s and Ridley’s disputations and examinations, and channelled other important writings to Protestant presses on the continent. Ridley marvelled at all Bernher did, writing “Brother Austen ye for our comfort renne up and down and who beareth your charges God knoweth”.23 It is the image of Bernher running up and down, connecting people in different places, that explains exactly why he appears so important by the measure of betweenness. He creates lots of paths that connect important people in the letter network, such as Bradford, Philpot, Careless, Hooper and Tyms. His connections with these figures make him very likely to be a node on a shortest path between two randomly selected nodes.

Betweenness, then, is a measure that highlights individuals within the network whose literary activities and social interactions allow connections between dispersed nodes and communities. It shows that infrastructural roles, like carrying letters, were of vital importance to the structure of the network, as well as its maintenance and furtherance. A similar, but crucially distinct, measure of importance is eigenvector centrality, which is closely related to the algorithm used by Google to assign importance to web pages in the World Wide Web, and to rank its search results by relevance. A node that has a high eigenvector score is one that is adjacent to nodes that are themselves high scorers. As Stephen Borgatti puts it, “the idea is that even if a node influences just one other node, who subsequently influences many other nodes (who themselves influence still more others), then the first node in that chain is highly influential”.24 So, while betweenness measures the importance of a node in the context of flow across the network – encapsulated by the image of Bernher running up and down the country – eigenvector centrality measures how well connected a node is to hubs and other significant nodes in the network. As with betweenness, several martyrs are ranked in the top twenty nodes for their social eigenvector centrality, and Bernher and Cooke also appear again. But the measure also ranks seven people who did not appear in the top-twenty for their betweenness rankings: Joyce Hales, William Punt, Joan Wilkinson, Anne Warcup, Robert and Lucy Harrington, and Robert Cole. Many of the same figures also show up in letter eigenvector rankings, with the addition of Catherine Hall, and Lady Elizabeth Fane.

So who are these figures? Punt, like Bernher is a known letter carrier, who made several trips to the continent delivering John Hooper’s letters to his wife Anne. He was also close to Bradford, and he was almost certainly the “W. P.” whom Bradford made co-executor of his books and to whom the martyr bequeathed two shirts.25 The remaining figures, with the exception of Cooke, Hales, and Hall all appear on John Strype’s list of sustainers, a group “who, by money, clothes, and provisions administered unto [the prisoners'] necessities”. 26 In an article on the role of women in the maintenance of the Protestant community Freeman has also identified Cooke and Hales as sustainers.27 By contrast, Catherine Hall was in receipt of the sustenance and support following her arrest and imprisonment along with her husband John and other members of a Protestant conventicle on New Year’s Day 1555 from Bradford, John Hooper, and Hales.

Such aid was rendered necessary by the private, for-profit status of sixteenth-century prisons. All prison staff, from the governors down to the turnkeys, purchased their position with the hope of recouping their initial investment, not from their salary, but rather from the prisoners in their custody.28 Prisoners would effectively pay rent, which would cover their bedding, food and drink; and additional fees would buy coal and candles, furniture and furnishings, and greater freedoms, such as use of the gardens, admittance of visitors, and even permission to conduct business outside the prison walls (as long as the prisoner stayed in the presence of a keeper and returned to his or her cell at night). 29 The money sent by the sustainers to Protestant prisoners, then, functioned to preserve their lives and health, as well as providing opportunities and means to get letters and other writings in and out of prison. The relationships established with the female sustainers in particular also occasioned the writing of several important treatises. Bradford’s “The Defence of Election” and “The Restoration of all Things” were written to comfort Joyce Hales, and his treatise on “The Hurt of Hearing Mass” was written to answer Lady Fane’s questions on the subject.

Which brings us to another point: five of the top twenty most well-connected nodes in terms of their social eigenvector centrality, and six in terms of their letter eigenvector centrality, are women. This is a striking statistic for a sixteenth-century network of correspondence between religious prisoners. One important reason why these women have been largely overlooked is because they do not necessarily look that important by other measures and statistics. Only 49 people in the network have a non-zero letter betweenness rating. This means that the majority of people in the network have no shortest paths going through them. More simply put, those with a zero betweenness rating are not in crucial positions for the passage of letters across the network. Part of this majority are Cooke, Lucy Harrington, Lady Fane and Warcup, who all rank bottom at 50/377. Yet, the measure of eigenvector centrality tells us that despite low letter betweenness they are still well connected. Why? One reason it that their acts of charity put them in direct contact with the hubs in the network, the martyrs. But this is not the only reason they were well connected.

Taking Margery Cooke as an example, we can see that these women were important nodes not only because they were friends of the martyrs, but also because of their particular social position. Cooke, who lived in Hadleigh, Suffolk, sent only one of the surviving letters in our dataset (to John Philpot), and received seven (six from John Careless and one from John Bradford), which is not a large amount of correspondence; but the commendations in these letters, as well as commendations to her in other letters, reveal that she not only had active connections with the Protestant community in Hadleigh, but also with co-religionists elsewhere in England. Cooke has shared edges with a total of 26 other nodes in the network, three of which are due to the communications listed above; the remaining 23 come through commendations. Of the people she shares edges with, three are martyrs (Careless, Bradford, Philpot), two are family (husband, mother), three are carriers (Punt, Richard Proude, William Porrege), three were co-religionists and/or sustainers who were associated with the underground London congregation (Lady Fane, John Ledley, Robert Cole), eleven were, at some stage, Freewillers associated with Kentish conventicles, although several converted (Hart, Cole, Ledley, Roger Newman, John Barry, John Gibson, Richard Porrege, Nicholas Sheterden, William Lawrence, Humphrey Middleton, William Kempe), another three were possibly Freewillers at some time, although doubt has been cast on this identification (William Porrege, Proude and Thomas Upcher).30 The identity and location of five other contacts – Master Heath, sisters AC and EH, and sisters Chyllerde, and Chyttenden - remains unclear. Nevertheless, we can see that Cooke’s significance in the network is not determined merely by her communication with the martyrs; she was well connected in her own right. Commendations and news show that she was believed to be in contact with a wide variety of different groups - infrastructural figures like Punt and Porrege, heretical leaders like Hart, known sustainers like Fane, and leaders in the London congregation like Cole – who were spread across the south-east of England.

This was our first foray into developing the idea of a network profile (or ‘fingerprint’) to understand categories of people. We developed this idea further in our article ‘Metadata, Surveillance, and the Tudor State’, History Workshop Journal 87 (2019), 27-51. Whereas here we use five network measures and develop bounded categories of people from their scores, in the HWJ piece we use eight network metrics and develop a method for finding the people with the closest profile, and ranking them in order of ‘closeness’. The latter method is remarkably successful in finding other people with a similar role in the network within the top fifteen to twenty search results. One of its main benefits is that it helps us to understand the commonalities in network properties within and between particular groups of people. As we write in the HWJ piece “Our tendency is to want to create bounded categories with labels, and ontologies, and to think about similarity in terms of those. This, however, can be counter-productive when thinking about people. Individuals can hold multiple official or unofficial roles in the network through time or simultaneously; the definition of roles may change through time and may not even be consistent at any one time; and roles may overlap. Instead, we propose, by thinking about similarity in terms of network properties rather than human-assigned categories we can begin to understand group identities in different ways, not least the shadings and slippage between those categories, thereby destabilizing them in productive ways.” (p. 20)

What the measure of betweenness and eigenvector centrality both bring to the fore, then, are infrastructural figures; individuals whose role may have been given minimal coverage in Foxe’s “Book of Martyrs”, or edited out all together.31 This clear patterning suggests the power of algorithms to predict the roles of different nodes within the networks - an idea we decided to test. By observing attributes of martyrs, carriers, and sustainers we were able to devise a set of quantitative criteria that separated the 377 nodes into seven categories according to their network properties, thereby predicting their roles within the network as a whole. These criteria consist of thresholds for five network measures: social betweenness, social eigenvector centrality, letter degree (the number of different senders and recipients connected to a node), letter strength (the total number of letters received and sent by a node), and non-letter social degree (the number of social links created by means other than letters). By using these thresholds to label values for each of these measures as high or low we arrive at the classification outlined in detail below. When tested, we found these predictions were largely accurate.

Three levels of leaders emerged from this analysis: prolific leaders, less prolific leaders, and a category that accounts for leaders who write common letters to a large number of named individuals (such as Bartlett Green, whose letter to Calthorpe, Bowyer et al was discussed above). The most interesting and illuminating distinctions arise between the first two categories. Prolific leaders were figures who ranked highly in all of the five measures: Bradford, Careless, John Hooper, Philpot, Saunders, Ridley and Tyms. These are figures that feature prominently in Foxe’s “Book of Martyrs”. By contrast, less prolific leaders ranked low for letter degree and social betweenness but highly for the other three measures. These were Hart, Latimer, Ferrar, Taylor, and Cranmer. What is interesting about these two groups is that we find a general division between the younger prisoners and the older Protestant leaders. The older members, by and large, sent letters to a small group of people, most of whom were other Protestant leaders, or, occasionally, family members. The most extreme example is Ferrar who wrote one letter each to Cranmer, Latimer, and Ridley; received letters from John Hooper, and Laurence Saunders; and had social links (through commendations etc.) with Tyms, Saunders, and Bradford. These are all what we might describe as short-range links, staying within an established, close-knit community of people from similar social backgrounds, and mostly covering only short geographical distances. Hart’s place in this category may be due to biases in the letter collection for, as a dissenter, his letters were probably not as desirable as the martyrs' works, but it may also signal isolation from the main, orthodox network of Protestants that will be probed further below.

By contrast, the younger martyrs like Bradford, Careless and Philpot seem to have understood the need to maintain links with dispersed and diverse communities – making long-range links, in other words – in order for the network to survive. We might conjecture that this can be put down to the fact that, because they were younger and had attained less high offices within the church, they were more in contact with the faith on the ground; or they may just have had more of a natural instinct for networking (in much the same way that the younger generations today make the most use of social networking sites). Certainly, as mentioned above, during his time as one of the chaplains in ordinary to Edward VI, Bradford had travelled through the country preaching reformation in Lancashire, Cheshire and possibly beyond. In a different way, Careless may have had found it easier to connect with a diverse range of people because of his former life as a weaver in Coventry.

The remaining nodes separate into three categories of network sustainers, and a final large category of peripheral figures (who do not rank highly in any of the five measures). The quantitative criteria used to identify the various levels of network sustainers generated a series of predictions that corresponds with Strype’s list of sustainers, but is broader in its definition, taking in the full range of infrastructural figures that our other methods have already identified. For example, major sustainers distinguish themselves through high social eigenvector centrality, high letter strength and relatively high non-letter social degree (and low values for the other two measures). People that fulfil these criteria are: Warcup, Bullinger, Wilkinson, Hales, Cooke, Lucy and Robert Harrington. As we have seen, Warcup, Wilkinson and the Harringtons all feature on Styrpe’s list, and Hales and Cooke have been identified by Freeman as one of the army of female sustainers that wrote and sent goods to the Protestant martyrs. Bullinger, by contrast, is a different kind of sustainer: through the correspondence sent between him and John Hooper, he links the imprisoned Protestant leader to co-religionists in exile in Zurich and beyond. More importantly, perhaps, Bullinger promises to write to Hooper’s wife, Anne, in exile in Frankfurt, providing emotional support for the family Hooper would leave behind when he was executed.32

Occupying another sustainer category by himself is Bernher, who stands apart from the other sustainers due to his high letter degree. This means that as well as connecting other people through his frequent role as carrier, his correspondence also makes him a minor hub. A third category, of minor sustainers, exhibits high social eigenvector centrality, and low values for all other measures. Individuals who fall into this category are John Bradford’s mother, Ledley, Cole, William Porrege and Punt. Most of these nodes can also be confirmed as infrastructural figures in the network. Ledley, Cole and Punt were all active members of the underground London congregation during Mary’s reign, which played a key role in the support of prisoners due to its proximity; William Porrege is mentioned as a carrier in several letters, and Foxe also describes him smuggling heretical literature into Kent. This leaves Bradford’s mother. Although she does not have the same characteristics as the other nodes identified by the thresholds for this category, her appearance here is easily explained by the fact that, as already discussed, she acted as a gateway to a broader community of co-religionists in the area around Manchester.

This is another section where we can think about different scales of reading: at the micro-, meso- and macro-scales. In this case we move from the meso-scale analysis that identified categories of people within the network, to understanding macro patterns about how they interact. We strongly believe that the macro- and meso- perspectives must always be validated and nuanced through the micro-perspective. For a more thorough discussion on the movement between different scales of reading, see The Network Turn, chapter 6, and Ted Underwood, Distant Horizons: Digital Evidence and Literary Change (Chicago University Press, 2019), passim.

By using quantitative criteria to establish categories we can see that those sharing similar profiles tended to occupy the same roles within the network. There are some slight anomalies (e.g. Hart, Bullinger and Bradford’s mother), but the broad effectiveness of the method demonstrates its value for sorting larger social networks than the one we have here, or to predict roles for those individuals where scant material survives. Moreover, the categorisation of nodes also allows us to identify general rules for the overall structure and function of the network. For example, by looking at how the different categories of nodes interact, we see that the most prolific leaders frequently and repeatedly wrote to network sustainers. If we look at Bradford, who sent the most letters of all the martyrs, we can see that out of 64 different people to whom he wrote, those he wrote to most often were: Hales (seven letters), Warcup (six), Lady Fane (five), Cole (four), and Wilkinson (four). All of these recipients are network sustainers. Similarly for Careless, the only two people he wrote more than three letters to are Cooke (six) and Bernher (four); for Philpot the only one is Lady Fane (five); and for Ridley it is Bradford (eleven) and Bernher (five). All except Bradford are network sustainers. Therefore we see that the quickest paths across the network were also the ones most frequently traversed by letters and, by implication, carriers. Perhaps more importantly, though, the method for categorisation can also alert us to patterns we might not have expected. In this case we see that several individuals who defected from the Freewillers are identified as network sustainers. Why might this be?

III. THE NETWORK UNDER ATTACK

Further to the note above, the case study is vital to drawing out the significance of patterns noticed at the macro-level. If we look at the size of the sub-network discussed in this particular case study (see figures 4, 5 and 6), we can see it represents less than 12% of the 377 nodes in this social network. However, by focusing on this sub-group we can understand not only the role of the Freewiller separatists in the network as a whole, but also connect this controversy to the observations we have already made about the structural importance of the female financial sustainers. This case study is pinned down through the close reading of individual letters.

The Freewillers are a group of people who have come up in a number of circumstances in this article. Henry Hart has been highlighted as a leader whose position in figure 2 (the graph plotting letter degree versus social degree, minus letter degree) showed him to be isolated from the orthodox majority within the network, with almost all his interactions occurring through letters rather than commendations. We have seen that, like his fellow Freewiller Jackson and two other adherents who later defected – Gibson and Gratwick – Hart had high betweenness. And we have discovered that Gibson and Gratwick were not the only significant nodes to defect: Cole and Ledey, two figures within the London congregation and key sustainers, were former-Freewillers; and William Porrege may have associated with these dissenters at some time. The question is: what do these little snatches of information tell us about the Freewillers as a dissenting community?

The difficulty of considering the interactions with Freewillers is that, despite being Protestants, they were also opponents. The Marian Protestant community was defined against the English Catholic state; similarly, the Freewillers defined themselves against the orthodox Protestant community. At the same time, however, it would not be right to exclude Freewillers from this study as being simple opponents of the underground Protestant community. Perhaps most importantly, from outside, orthodox Protestants and Freewillers were perceived as one single dissident group. The doctrinal conflict merely confirmed the authorities' charge that Protestants were an inherently “factious and divisive” people.33 It should also be considered that boundaries between the Freewillers and those that held to predestinarian beliefs were not stable: Freewillers sought to convert Protestants to their cause, whilst the leaders of the orthodox Protestant community launched a counter-attack, which was successful in causing a number of the dissenters to defect to predestinarian beliefs. By considering the Freewillers as hostile elements within the network, we can model how the Protestant community responded to and overcame internal attack. For, as noted above, this separatist group lasted for only ten years: by the time Elizabeth I ascended throne, the Freewillers had all but died out.

Why this group died out has been a question that has troubled scholars.34 One reason for this is that, as Freeman has pointed out, their organisation should have been strong, based as it was on congregations and conventicles established in Edward VI’s reign, if not earlier. In fact, he argues that “because the ‘orthodox’ Protestant church was weakened and outlawed in Mary’s reign, the Freewillers were closer to parity with the Protestant leadership than any subsequent dissenters”.35 Nevertheless, Freeman’s work and various other studies have shown how, in many ways, the demise of this group was overdetermined. The leaders lacked theological training and the credibility that it provided; they were from comparatively poor social and financial backgrounds; the movement lacked prominent martyrs; it lost a number of key figures who defected to predestinarian positions; and they failed to foster the close pastoral relationships that played such a crucial role in the maintenance of the Protestant community during persecution.36 Such a summary suggests there was no one simple reason for their demise, but rather a whole collision of factors. However, their demise can be described much more simply by taking a network perspective.

One of the standard concerns raised about the application of quantitative measures to historical archives is the impact of missing data. The incompleteness of network data however is not a problem that is specific to historical networks. Throughout the interdisciplinary field of ‘network science’ researchers have to work with incomplete networks, and to interpret their quantitative results in light of this. The partial absence of network connections does not necessarily invalidate quantitative analysis. A recent investigation by us in collaboration with Yann Ryan found that most network metrics are relatively robust to the random removal of letters in correspondence networks, even on a fairly large scale. See Yann C. Ryan and Sebastian E. Ahnert, “The Measure of the Archive: The Robustness of Network Analysis in Early Modern Correspondence,” Journal of Cultural Analytics (2021) https://doi.org/10.22148/001c.25943.

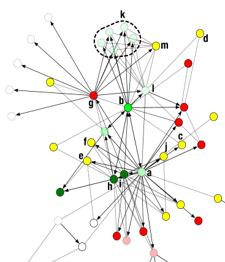

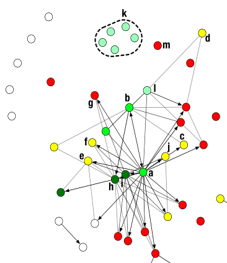

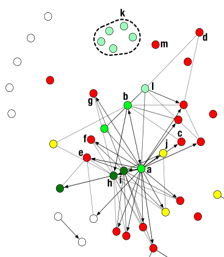

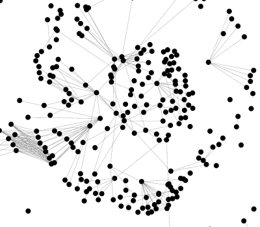

Figs 4 (top), 5 (middle), and 6 (bottom):

The ntwork of freewillers (red), Protestant leaders (green), converted freewillers (yellow) and sustainers (dark green) on 1 March 1555 (figure 4), 14 March 1555 (figure 5) and 20 June 1556 (figure 6). Individuals who have died are shown faded.

One important thing to point out again here, however, is the bias of the letter collection we have available to us. The collection, which is largely focused around correspondence involving the martyrs, means that we have no surviving letters that were sent between Freewillers, so we do not know the extent to which this was a textual community, and to what extent its communities were locally constituted and maintained. What we do, have, however, is a significant number of letters which document interactions between the orthodox and Freewiller communities, especially regarding the disputes between representative from these two communities held in the King’s Bench prison. In other words, we cannot uncover the internal workings of the Freewiller community, but we can chart their external interactions. The way we can trace this is by creating a partial network visualization of the Freewillers and their neighbors only (i.e., any people who have a direct social or letter link with members of this community). Figures 4, 5 and 6 show the Freewillers and their neighbors at three dates, 1 March 1555, 14 March 1555, and 20 June 1556, and thus how the network evolved over time. Freewillers are shown in black, key orthodox Protestants are shown as light grey with circles, network sustainers are in light grey with squares, and those defecting from the Freewillers in dark grey (this category also includes those people who are suspected as having been Freewillers at some point). Each node is crossed through when they die; links through letters are in black and all other social links are in grey. What we see is that at this point of interface between the Freewillers and the orthodox community, the orthodox community consistently takes ground (including converting nodes), while the Freewiller base is challenged.

By focusing on all the interactions between Freewillers and their direct neighbors we can immediately observe the extent of the communication between two orthodox Protestant leaders, Bradford and Careless (marked as “a” and “b” in figures 4, 5 and 6), and the Freewillers. Although Bradford and Careless were in communication with other leaders, such as Philpot and Ridley about the doctrinal threat posed by Hart and his companions, they were the ones who spent the most time fighting schism through their letters and other writings. For this reason, even in this sub-network, Bradford and Careless are the hubs. The volume of links they make, and the number of people who convert to orthodox belief following communication with these martyrs suggests a causal link. For example, by looking at figures 4 and 5 we can see that Bradford’s links with Roberts Skelthorpe (c), Cornelius Stevenson (d), Cole (e), and Ledley (f) predate their conversion. The selected frames from the evolving network also show March 1555 to have been a key moment in the battle between Freewillers and predestinarians, as four figures seem to have defected in the first two weeks of the month. By comparison, identified “leaders” of the Freewiller community look comparatively peripheral. This is particularly striking given the fact that the whole network focuses on Freewillers and their direct neighbours only. Moreover, the contacts that Hart (g) makes are not followed by conversion.

The orthodox side in this struggle may have had the most influential hubs, but that is only one reason for its dominance. It also appears to have had a more robust infrastructure. Several figures that have already been identified as network sustainers appear within this sub-network: Cooke (h), Hales (i), Cole (e), Ledley (f), and William Porrege (j). Although Cole and Ledley started out on the side of the Freewillers (as Porrege may have done too), it is crucial that they end up on the side of the predestinarians. As seen above, they seem to have defected at some point in March 1555, but it is only after this conversion that they gained the attributes of network sustainers. Living together with their wives and Punt in Grace Street, London, after fleeing persecution in Kent, these men are reported to have served the Protestant prisoners held in London jails, as well as relaying information and books to and from the Protestant exile community.37 These were not the only significant losses. In early 1556 Gratwick (m) and Gibson (n) also defected from the Freewillers. As we saw earlier, both these men figured in the top twenty nodes for their letter betweenness.

Not only did the Freewillers lose key infrastructural nodes to their opponents, they also failed to make any converts from this constituency. This was not for lack of effort. We can see a number of nodes in figure 6 that the Freewillers sought and failed to convert. Freewillers inside and outside prison tried to win souls for the cause. Prisoners condemned to death – who were usually held in Newgate until their executions – were a particular target. Hart sent a statement of his beliefs to William Tyms, Christopher Lister, Robert Drake, George Ambrose, Richard Spurge, Thomas Spurge, Gratwick, Richard Nicholl, John Spenser, John Harman and Simon Jen, which they then returned to him on 3 April 1556 with a signed refutation his belief bearing all of their names.38 We can see the battle that was fought over some of these men: Cavell, Drake, Ambrose, and the Spurges (k) each share edges with nodes from both sides of the controversy in figure 6. Yet while they share an edge with only one Freewiller, Hart (g), they share edges with three predestinarians: Careless (b); Tyms (l), who signed the letter rejecting Hart’s doctrines; and Gratwick (m), who had defected from the Freewilles earlier that year. Careless’s edge, in particular, is marked by a letter, showing that this leader did not leave his vulnerable co-religionists undefended.

Another example of this protection of key co-religionists can be traced in the communications of Bradford and Careless with Cooke and Hales. We know that both women were troubled by the doctrine of free will, which they came in contact with either through Hart’s writings, or through some interaction with local conventiclers, or perhaps both. If the Freewillers had been successful in convincing these women of the veracity of their beliefs, they would have won more than coverts. Whilst the battle over Tyms’s and the Spurges' souls might have gained the Freewillers martyrs for their cause, the conversion of Hales or Cooke would have been a much more tactical victory. Bradford’s and Careless’s dedication pastoral care, and their particular regard for these women can be seen by the great effort these two leaders went to in order to make sure they were correctly informed on the topic of election. As already mentioned above, Bradford wrote letters to both Cooke and Hales on this topic, and he dedicated a treatise entitled “The Defence of Election” to Hales. Bradford also wrote to Hart, John Barry, Ledley, Cole, Richard Proude, Nicholas Sheterden, William Porrege, Roger Newman William Lawrence, John Gibson, Richard Porrege, Humphrey Middleton, William Kempe and others abiding in Kent, Essex, Sussex and thereabout, just before his execution warning them:

it hathe pleased god by my mynistrie to open vnto [Joyce Hales] his trothe wherein as she is settled and I trust in God confirmed so if you cannot thynke with her therein as she duth I heartelie praie you […] that you molest her not nor disquiet her[…]. I commend also vnto you my good sister Margerie Coke, making for her the like sute vnto you.39

The letter suggests that some of the men may have previously attempted to convert Cooke and Hales to the doctrine of free will. But the letter is slightly problematic for, at the same time as warning these men not to tempt these women into error, it places Hales in a vulnerable position. Near the beginning of the letter Bradford tells the recipients about the treatise he has written for Hales and commends it to them as profitable reading material. The fact the later commends the woman “with whom I leave this letter”, Hales, suggests that this missive had been sent as an insert to another letter sent to Hales, or perhaps with the treatise itself. Therefore, Bradford has made it necessary for Hales to make contact with at least one of the recipients of the letter in order to pass it on. In this way, he is making use of the very quality that made Hales such an attractive convert – her identity as a major network sustainer. Bradford wants to warn these men not to continue in their attempts to convert her, but at the same time she is the most straightforward means of connecting with them; or, to consider this from a network perspective, she offers the shortest path.

Bradford and Careless sent letters such as this because they cared about Hales and Cooke and their salvation. This is understandable: these women had supported them and written to them often during their imprisonments. But, as the use of Hales in the letter above shows, these two leaders clearly also recognised the infrastructural role Hales and Cooke served within the community, and the great damage that would be done to their cause if they lost them. It appears that Bradford and Careless understood by instinct a key feature of networks that scientists have only more recently grasped: that the robustness of a network relies on figures who encourage high levels of interconnectivity. This goes for all networks: “a cell’s robustness is hidden in its intricate regulatory and metabolic network; society’s resilience is rooted in the interwoven social web; the economy’s stability is maintained by a delicate network of financial and regulatory organizations; an ecosystem’s survivability is encoded in a carefully crafted web of species interactions."40 Despite these structures, however, all networks are vulnerable to failure, whether through attack, or errors of design. Node failures can easily break a network up into isolated, non-communicating fragments. In an online system this might be caused by hackers; in a social or ecological network it could be caused by illness or death. What studies have shown is that one of the most effective ways to fragment a network into separate communities is to remove nodes with the highest betweenness (a key measure of interconnectivity in the network).41

Networks are often treated as static entities, as this makes their analysis much easier. If the temporality of each connection is taken into account we enter the domain of temporal network analysis (see Holme & Saramäki, ‘Temporal networks’, Physics Reports, 519.3 (2012), 97-125), which is a relatively new and rapidly evolving field. The analysis of temporal network data requires careful thought when it comes to the definition of edges and nodes – do edges persist for good after being created? Are nodes removed if a person dies? These decisions affect the quantitative results of the analysis and their interpretation in the context of historical scholarship.

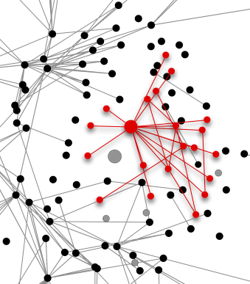

As mentioned in this paragraph we made a video during our research that visualises the changing shape of the network across the period covered by the letters, which shows the impact of the execution of the Marian martyrs. This dynamic visualisation provides a compelling piece of visual evidence that is difficult to convey through static images (see figures 7 and 8). If one wants to publish in journals that are imagined primarily as print publications, there are usually not many ways to present dynamic visualisations. However, a number of publication venues in the arts and humanities are now thinking about how they can make supplementary evidence and resources available online, as is already commonplace in scientific journals. For work like this, it is very appealing to work with such publication venues. A potential trade-off however is that the venues exploring these options are often those already speaking to communities working in digital and quantitative methods. If the aim is to write for a home discipline that is not yet engaging with these approaches as much, one may need to make a choice.

Fig 7 (top) and 8 (bottom):

The immediate environment of John BRadford in the network immediately before (Figure 7) and after (Figure 8) his death on 1 July 1555. John Bradford is highlighted as the larger black (Figure 7) and gray (Figure 8) node. The network only shows the connections of living individuals. Joh Bradford’s death separated an entire subnetwork (shown in red), centered around John Bradford’s mother (larder red node), from the rest of the network.